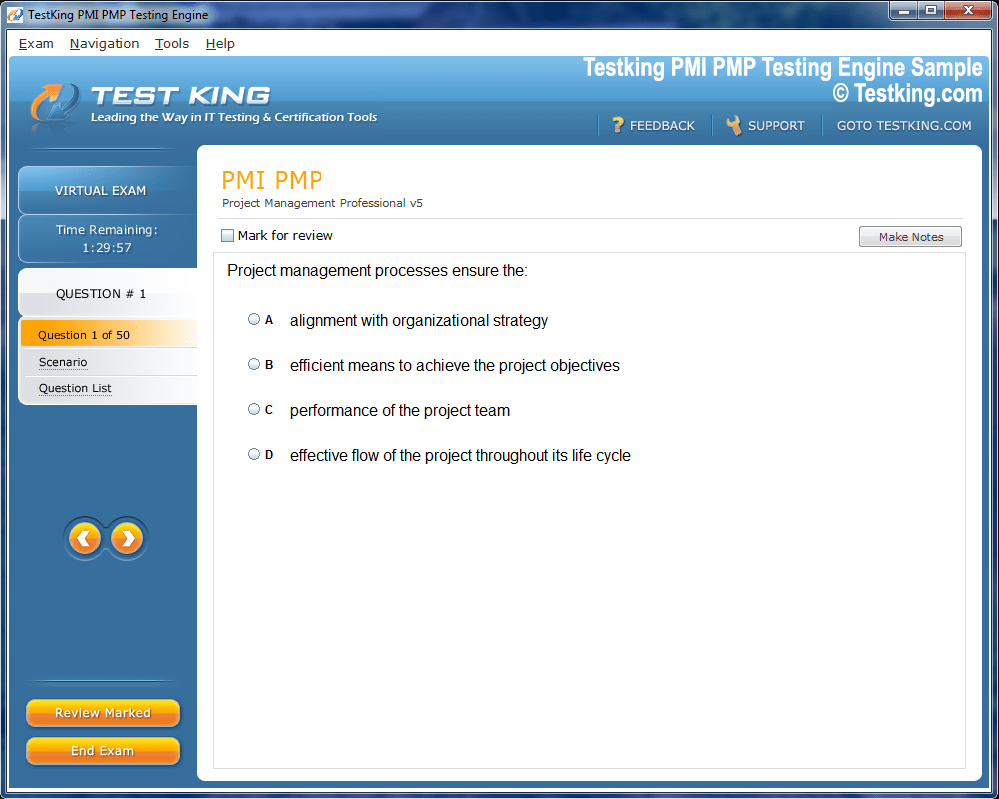

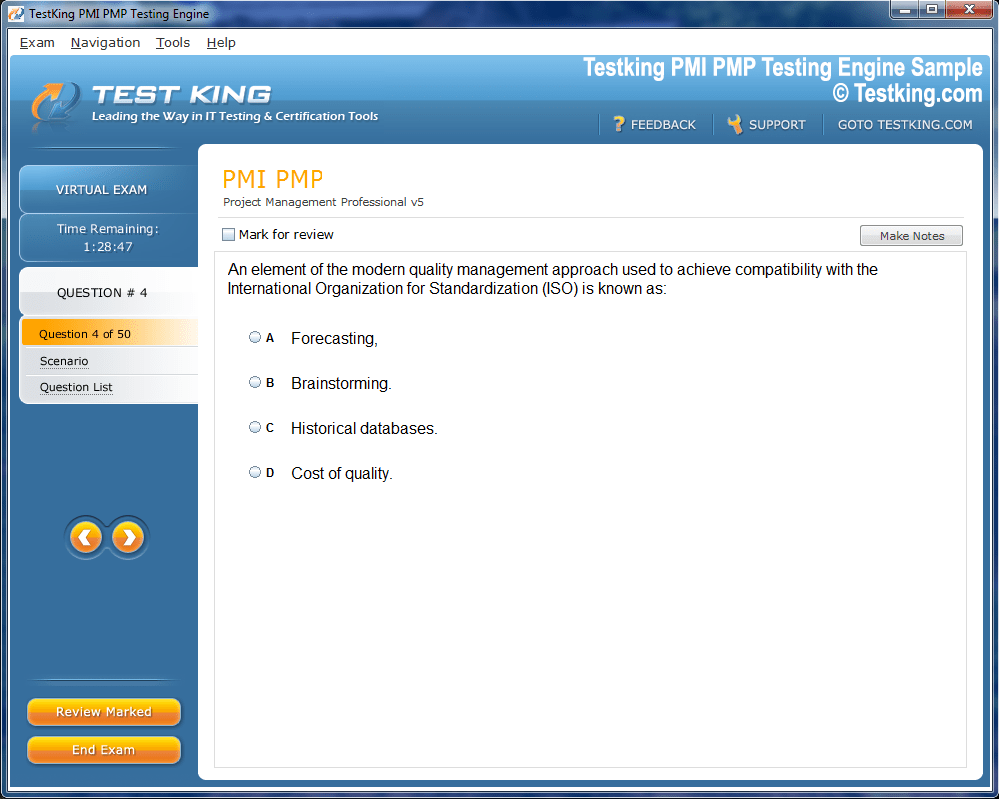

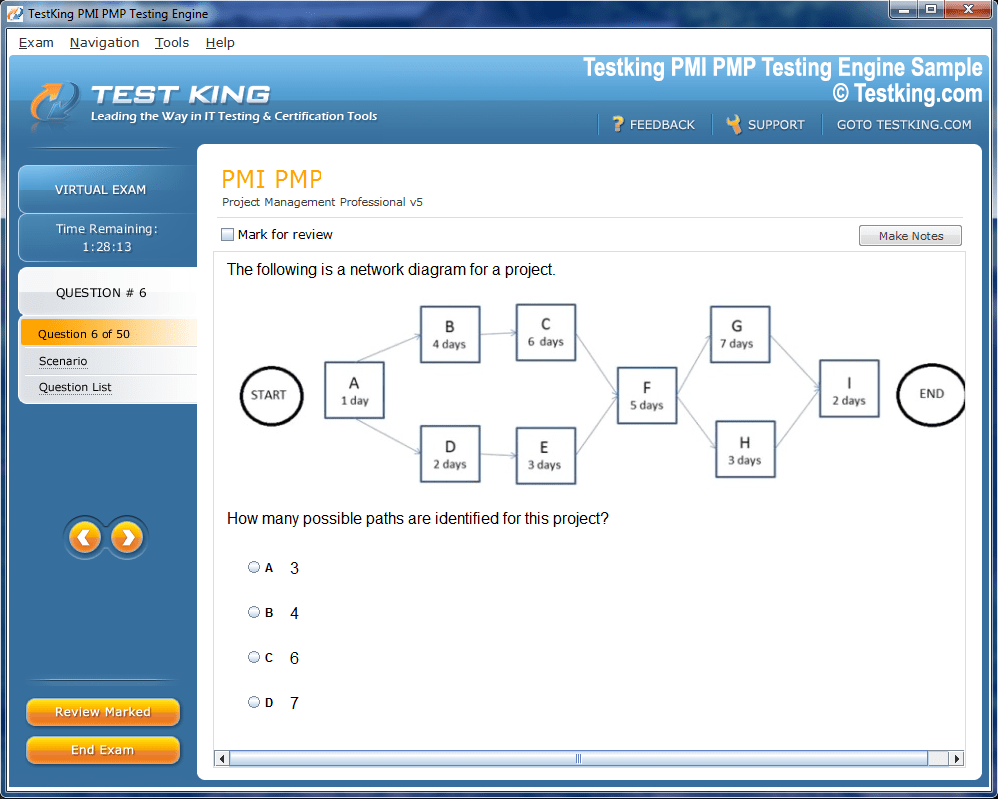

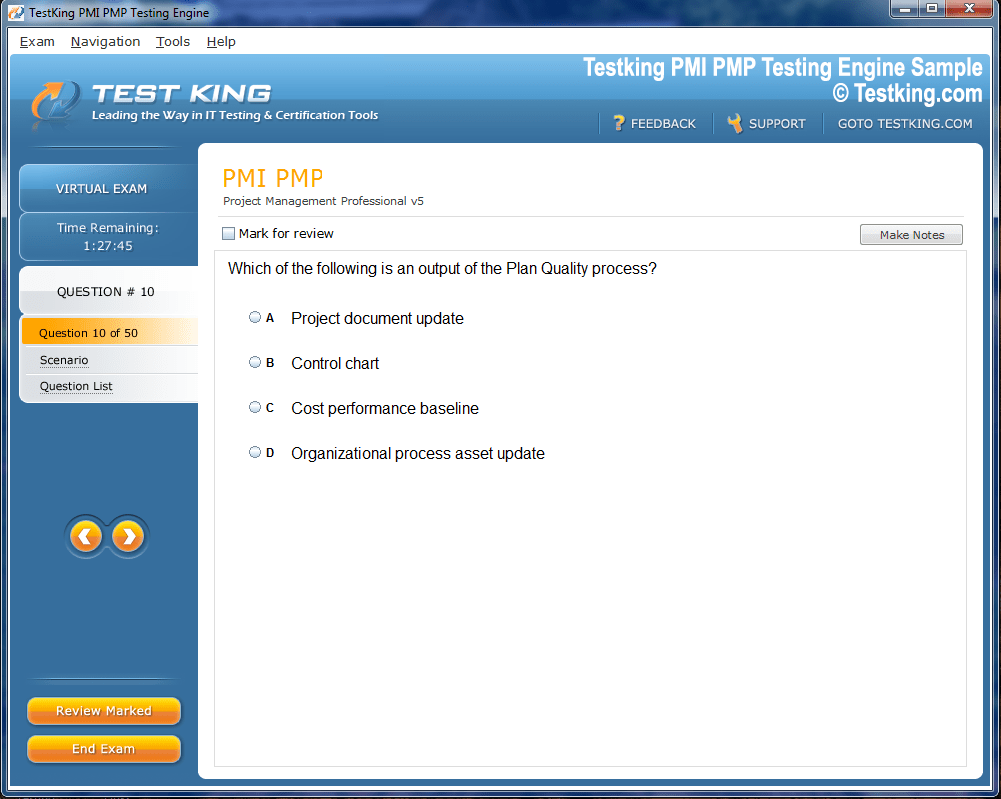

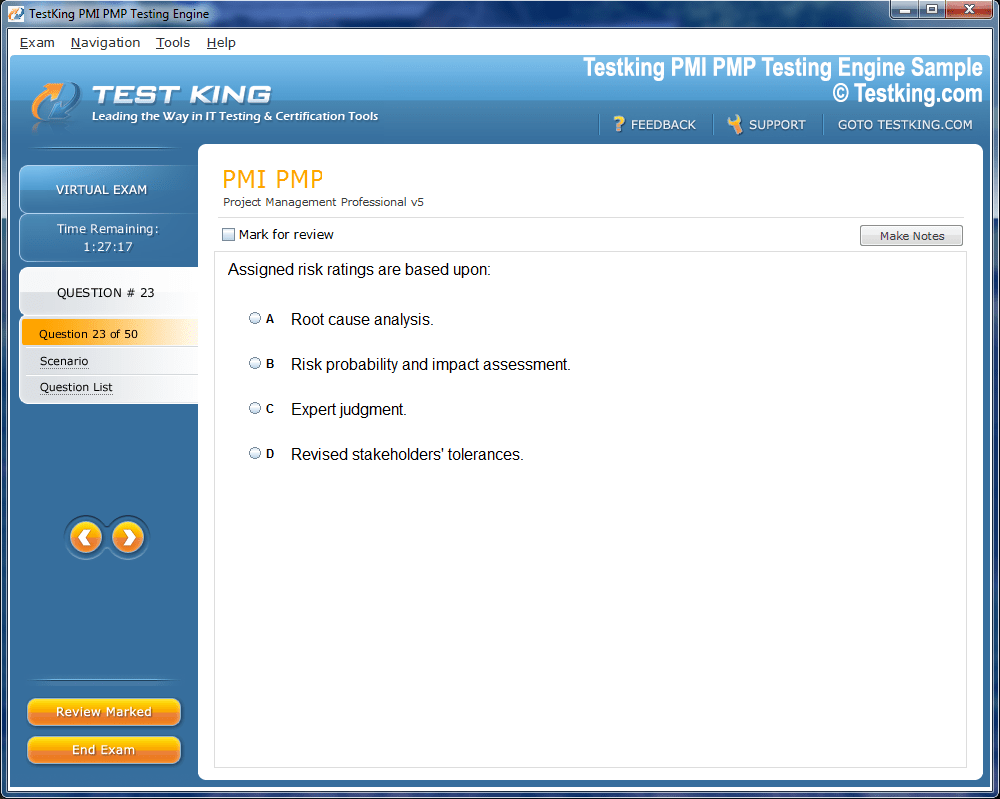

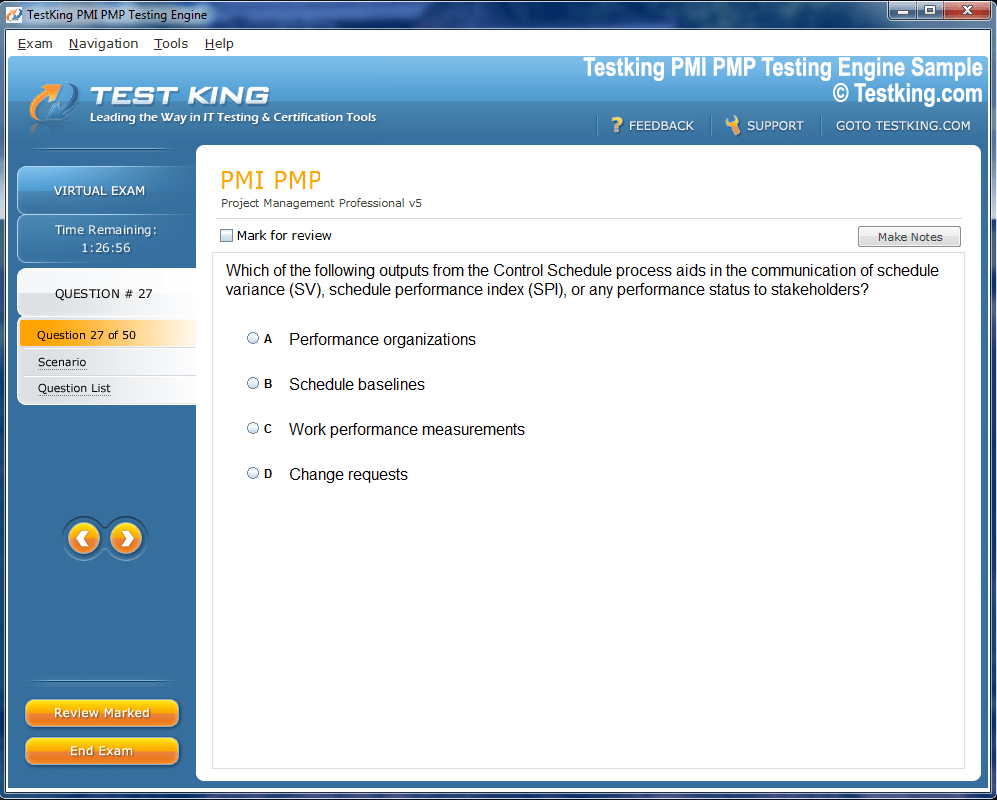

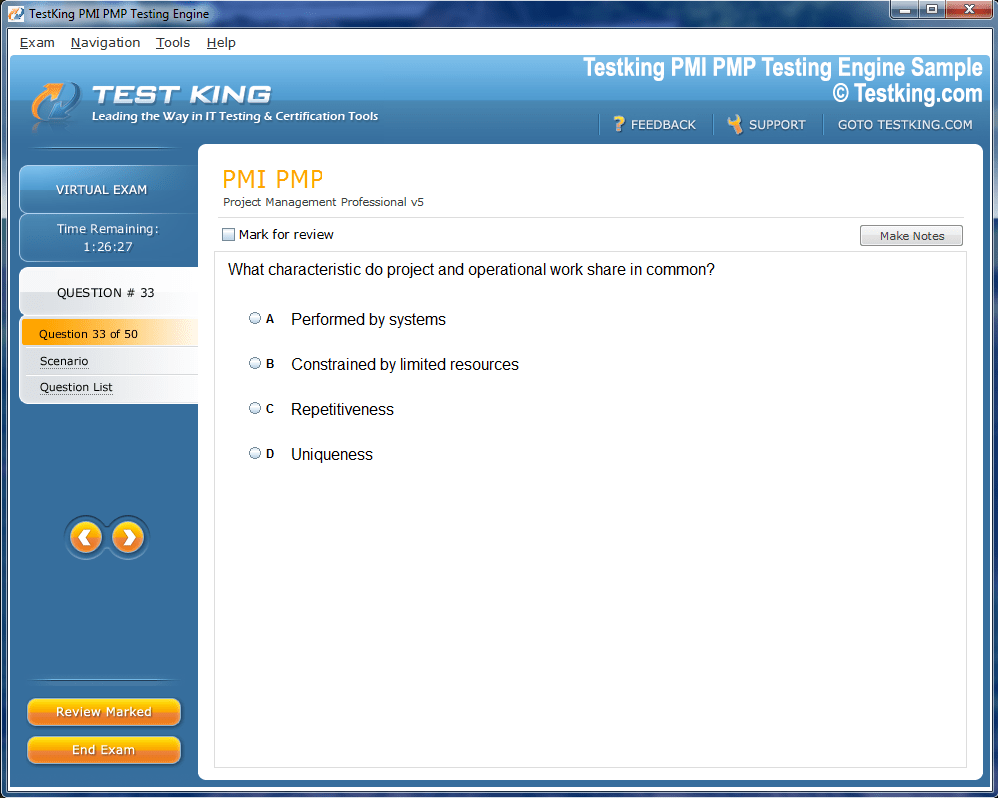

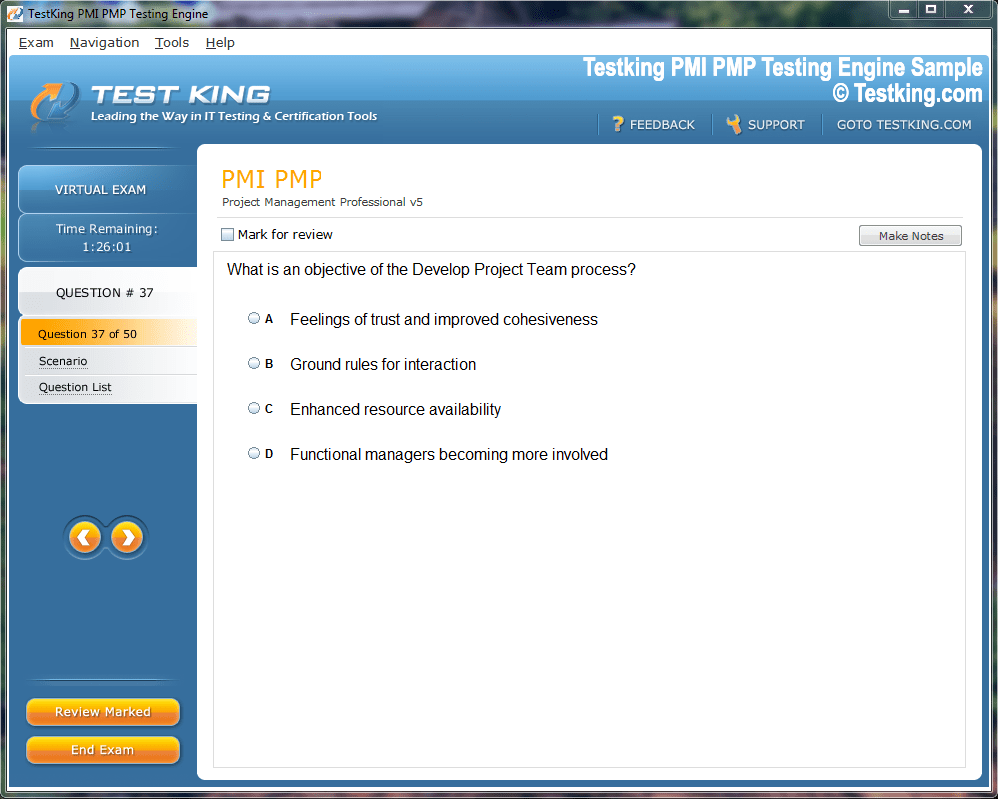

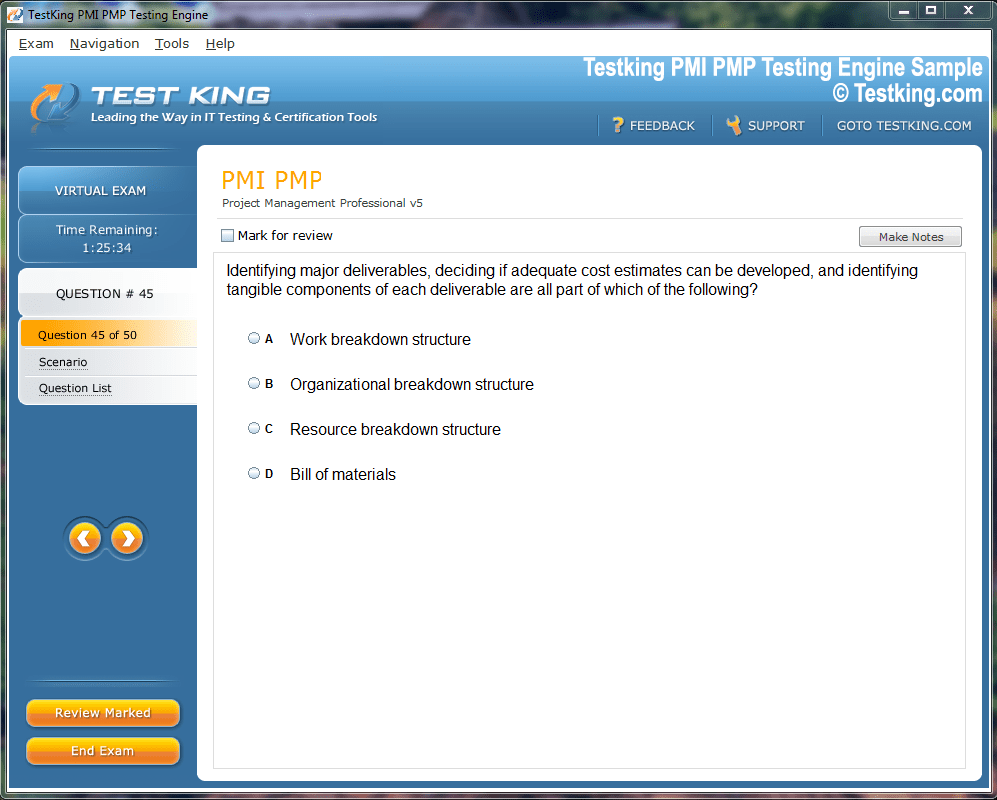

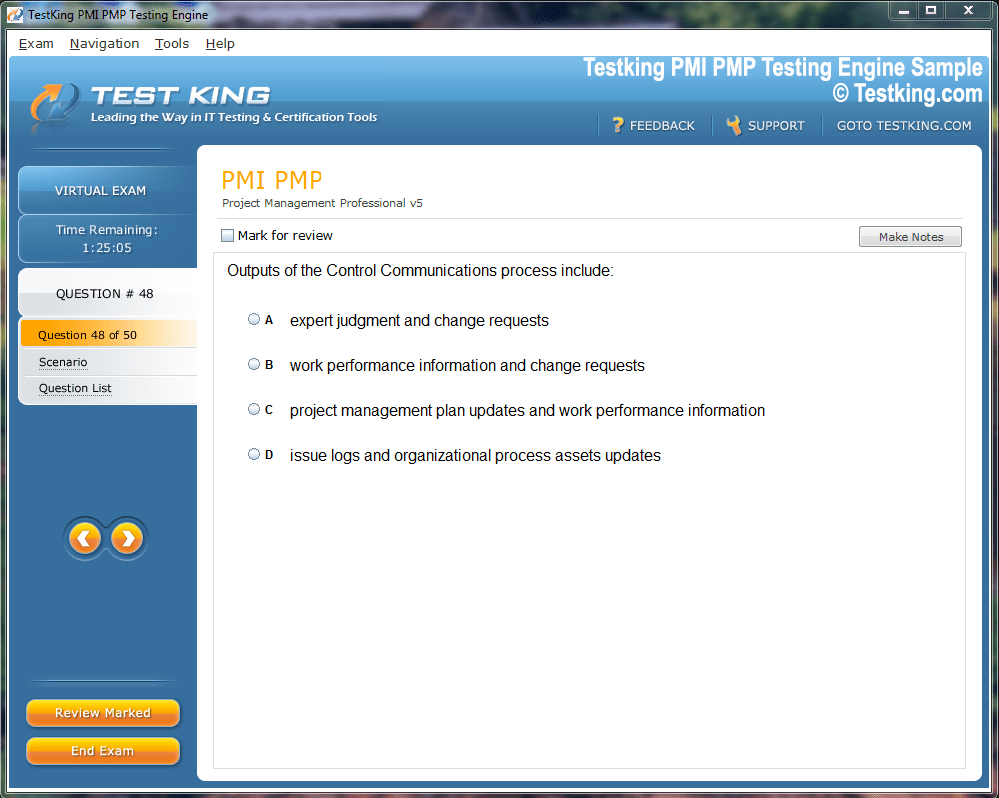

Product Screenshots

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I download my products after I have completed the purchase?

Your products are available immediately after you have made the payment. You can download them from your Member's Area. Right after your purchase has been confirmed, the website will transfer you to Member's Area. All you will have to do is login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long will my product be valid?

All Testking products are valid for 90 days from the date of purchase. These 90 days also cover updates that may come in during this time. This includes new questions, updates and changes by our editing team and more. These updates will be automatically downloaded to computer to make sure that you get the most updated version of your exam preparation materials.

How can I renew my products after the expiry date? Or do I need to purchase it again?

When your product expires after the 90 days, you don't need to purchase it again. Instead, you should head to your Member's Area, where there is an option of renewing your products with a 30% discount.

Please keep in mind that you need to renew your product to continue using it after the expiry date.

How many computers I can download Testking software on?

You can download your Testking products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers/devices. To use the software on more than 2 machines, you need to purchase an additional subscription which can be easily done on the website. Please email support@testking.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our 4A0-205 testing engine is supported by all modern Windows editions, Android and iPhone/iPad versions. Mac and IOS versions of the software are now being developed. Please stay tuned for updates if you're interested in Mac and IOS versions of Testking software.

Top Nokia Exams

- 4A0-100 - Nokia IP Networks and Services Fundamentals

- 4A0-102 - Nokia Border Gateway Protocol

- 4A0-116 - Nokia Segment Routing

- 4A0-103 - Nokia Multiprotocol Label Switching

- 4A0-105 - Nokia Virtual Private LAN Services

- BL0-100 - Nokia Bell Labs End-to-End 5G Foundation Exam

- 4A0-112 - Nokia IS-IS Routing Protocol

- 4A0-C03 - Nokia NRS II Composite: IS-IS version

Key Concepts You Need to Know for Nokia 4A0-205: WDM, EPT & NFM-T

The evolution of telecommunications networks has been shaped by the ever-growing need for capacity, speed, and resiliency. Optical fiber, once seen as a limitless medium, soon met practical constraints as bandwidth demands surged exponentially. This challenge inspired one of the most transformative innovations in optical networking—Wavelength Division Multiplexing, commonly abbreviated as WDM. It is a cornerstone of modern transport networks and a crucial subject in the Nokia 4A0-205 Optical Networking Fundamentals exam, which measures not only theoretical comprehension but also the ability to apply design logic to real-world optical infrastructures.

The Genesis of WDM Technology

In the earliest days of fiber transmission, a single optical channel carried one data stream per fiber pair. As the hunger for higher throughput intensified, deploying new fibers for each capacity upgrade became financially and logistically untenable. Engineers realized that multiple light signals could coexist within the same fiber if each was assigned a distinct wavelength. Thus, WDM emerged—a technology that permits simultaneous transmission of numerous channels through a single optical medium without mutual interference.

The principle is elegantly simple yet technically profound. Each transmitter emits light at a unique wavelength, corresponding to a discrete color within the optical spectrum. These multiple wavelengths are then multiplexed into a unified optical signal for transmission and demultiplexed at the receiver end. This multiplexing process forms the backbone of efficient optical systems such as Nokia’s 1830 Photonic Service Switch, which leverages WDM to deliver scalable, resilient, and high-density optical connectivity.

Fundamentals of Light and Transmission

To grasp the core of WDM, one must first appreciate the properties of light in fiber. Optical signals are electromagnetic waves propagating at frequencies between infrared and visible light. Their speed in a vacuum is a constant, but within the fiber core, it slows due to the refractive index of the material. Wavelength and frequency maintain an inverse relationship—shorter wavelengths carry higher frequencies, while longer wavelengths travel slower. In optical networks, this relationship defines how signals occupy distinct spectral slots, enabling dense signal packing without crosstalk.

The fiber itself is a composite of the core, cladding, and protective coating. The refractive index differential between the core and cladding ensures total internal reflection, guiding light efficiently over long distances. However, attenuation and dispersion affect the signal’s amplitude and integrity. These impairments necessitate careful selection of operating wavelengths, amplifiers, and dispersion compensation techniques—all integral to mastering WDM design.

CWDM and DWDM: Two Approaches, One Vision

WDM manifests primarily in two variants: Coarse Wavelength Division Multiplexing (CWDM) and Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM). CWDM employs wider channel spacing, typically around 20 nm, supporting up to 18 channels across the optical spectrum. It is suitable for metropolitan and access networks where cost efficiency outweighs ultra-high capacity. Conversely, DWDM features narrow spacing, often 0.8 nm or 100 GHz, allowing transmission of dozens or even hundreds of channels on a single fiber pair. This dense arrangement is indispensable in backbone and long-haul networks where spectral efficiency and scalability are paramount.

The distinction between CWDM and DWDM is not merely quantitative; it reflects divergent engineering philosophies. CWDM prioritizes simplicity, passive components, and low power consumption. DWDM emphasizes precision, stability, and amplification. In the Nokia ecosystem, DWDM technology underpins optical line systems that connect service routers and packet optical transport layers with unparalleled capacity and flexibility.

Multiplexing and Demultiplexing Mechanisms

The process of multiplexing multiple wavelengths into a single optical path relies on sophisticated components such as diffraction gratings, arrayed waveguide gratings, and thin-film filters. Each device manipulates the phase and angle of light to separate or combine wavelengths with surgical accuracy. A multiplexer (MUX) integrates the discrete optical channels into one composite signal for transmission, while a demultiplexer (DEMUX) performs the reverse operation at the receiving node.

Modern optical nodes frequently employ reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs). These devices enable dynamic wavelength routing without converting optical signals to electrical form, a feature that dramatically enhances flexibility and simplifies network operations. By adjusting wavelength assignments on demand, ROADMs support rapid provisioning and automatic rerouting, essential in large-scale carrier networks.

Optical Amplification and Signal Regeneration

As optical signals traverse extended distances, they encounter inevitable power decay due to fiber attenuation and connector losses. Amplifiers compensate for this decay, allowing signals to reach far-flung nodes without regeneration. The most common type, the Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA), operates within the C-band of the optical spectrum and can amplify multiple channels simultaneously. EDFAs are pivotal in DWDM systems, sustaining long-haul transmission without the latency or cost penalties of optical-electrical-optical conversion.

In scenarios where dispersion or non-linear effects degrade signal integrity beyond amplification’s reach, regeneration becomes necessary. Optical regeneration restores both amplitude and shape of the signal, often in three stages: reshaping, retiming, and re-amplifying. Although regeneration incurs higher complexity, it remains a critical consideration in designing ultra-long-haul optical networks and understanding their operational constraints within the 4A0-205 curriculum.

Optical Spectrum and Channel Planning

Efficient utilization of the optical spectrum requires meticulous channel planning. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) defines grid standards that specify frequency intervals for DWDM systems. Channels are typically spaced at 100 GHz, 50 GHz, or even 25 GHz in advanced implementations. Channel spacing determines how many wavelengths can coexist and influences filter design, amplifier gain flatness, and non-linear interference. Engineers must balance these parameters to maximize spectral efficiency without compromising reliability.

Channel equalization ensures uniform optical power across wavelengths, preventing weaker signals from being overshadowed. This process, though technical, exemplifies the artistry of optical engineering—harmonizing physical limitations with performance aspirations.

Nonlinearities and Optical Impairments

Optical fibers, while remarkably transparent, are not immune to physical phenomena that distort signal propagation. Nonlinear effects such as self-phase modulation, cross-phase modulation, and four-wave mixing arise when high optical power interacts with the fiber’s refractive index. These phenomena introduce phase noise, inter-channel interference, and unpredictable spectral components. Dispersion, meanwhile, causes pulse broadening that erodes bit distinction over distance. Mastery of these impairments is fundamental for any engineer pursuing Nokia’s optical certification, as mitigation defines the difference between theoretical capacity and achievable performance.

Advanced compensation techniques include dispersion-shifted fibers, digital signal processing, and coherent detection systems. Coherent receivers, capable of capturing both phase and amplitude, have revolutionized optical transmission by enabling higher-order modulation formats and real-time impairment correction.

Network Design Principles with WDM

Designing a WDM network involves more than stacking wavelengths; it requires architectural insight and analytical precision. Planners must evaluate topology, link budgets, amplifier placement, and wavelength assignment strategies. A link budget calculation determines the maximum reach of a signal by balancing transmitted power against losses from fiber, splices, connectors, and multiplexing elements. Each design parameter affects cost, latency, and service scalability.

In a multi-layer architecture, optical transport coexists with packet and service layers. The optical layer provides raw bandwidth, the packet layer manages aggregation and switching, and the service layer delivers end-to-end applications. Harmonizing these layers ensures seamless operation, simplified fault management, and efficient restoration in case of fiber cuts or equipment failure.

The Role of Automation and Control

Modern WDM systems transcend static configurations through integrated management and control systems. Automation enables centralized supervision of optical elements, wavelength assignments, and fault recovery. Technologies such as software-defined networking extend programmability into the optical domain, fostering adaptive capacity allocation and intelligent route optimization. In Nokia’s ecosystem, these capabilities are coordinated through platforms like the Network Functions Manager for Transport (NFM-T), which orchestrates both optical and packet domains to maintain cohesive service performance.

Such orchestration epitomizes the future of optical networking—fluid, dynamic, and self-optimizing. Engineers no longer operate isolated devices; they cultivate a symphony of interconnected optical elements guided by intelligent algorithms.

Testing and Maintenance Considerations

Operational integrity in WDM networks relies heavily on precise testing and continuous monitoring. Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (OTDR) is a cornerstone technique that identifies fiber faults, reflections, and attenuation points along a span. Power meters, optical spectrum analyzers, and coherent receivers further contribute to real-time performance evaluation. These instruments ensure that each wavelength channel adheres to expected parameters, safeguarding service quality and minimizing downtime.

Proactive maintenance strategies are equally vital. Cleaning connectors, calibrating amplifiers, and verifying optical power balance prevent cascading failures that could compromise entire spans of the network. Through such practices, network reliability transitions from reactive repair to predictive stability.

Future Directions of WDM Technology

WDM continues to evolve as network demands outpace traditional architectures. Innovations in superchannel design, flexible grid allocation, and space-division multiplexing are expanding capacity far beyond classical limits. The fusion of photonics with digital control heralds a new epoch of elastic optical networks, capable of adapting spectrum allocation in real time to meet fluctuating service demands. Such evolution ensures that WDM remains indispensable in the transformation toward 5G backhaul, cloud interconnection, and future transport paradigms.

The concept of integrating photonic intelligence into the control layer also introduces self-healing capabilities, where networks autonomously detect and mitigate faults. As the boundaries between optical and electronic domains blur, engineers equipped with solid WDM foundations will command the expertise necessary to shape the next generation of global connectivity.

Exploring EPT Architecture

Ethernet Protection Transport, often referred to as EPT, is one of the most significant frameworks in optical networking that ensures reliability, continuity, and resilience of data transport over carrier-grade Ethernet. Within the Nokia optical ecosystem, EPT integrates with photonic and packet domains to create a robust structure capable of surviving failures without disrupting services. Understanding its principles is indispensable for engineers preparing for the Nokia 4A0-205 exam, as it connects Ethernet agility with optical reliability.

Evolution of Carrier Ethernet Protection

Ethernet was originally designed for local area networks, prioritizing simplicity and flexibility over determinism and reliability. However, as service providers adopted Ethernet for metro and transport networks, the need for mechanisms that could guarantee predictable recovery times became apparent. Conventional Ethernet’s Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) provided loop avoidance but suffered from slow convergence, often measured in seconds—unacceptable for carrier-grade applications.

This challenge gave birth to protection schemes that combined the speed of transport-grade resilience with the scalability of Ethernet. EPT emerged as a solution that merges optical path restoration principles with Ethernet forwarding, offering sub-50-millisecond recovery comparable to traditional Synchronous Digital Hierarchy systems.

Foundations of EPT Operation

At its core, EPT operates on the principle of dual connectivity between two network elements. These elements are linked via two diverse paths—designated as the working and protection links. Traffic normally traverses the working path, while the protection path remains in standby mode. Upon detecting a fault in the working path, EPT initiates a rapid switchover that redirects traffic to the protection link, ensuring minimal service interruption.

Unlike basic link aggregation or manual failover, EPT is automated, deterministic, and symmetrical. Each node maintains awareness of both paths’ operational states, enabling instantaneous decision-making. This architecture offers high availability, making it ideal for business-critical, latency-sensitive services that cannot tolerate packet loss or prolonged downtime.

Structural Components and Logical Framework

An EPT domain is typically composed of interconnected network elements that collectively participate in a protection group. Each protection group manages a pair of Ethernet interfaces—one active and one standby. Within this group, control messages are exchanged periodically to monitor link health and synchronization status. These control messages form the heartbeat of the EPT system, ensuring continuous awareness of both ends’ state.

The mechanism depends heavily on Continuity Check Messages (CCMs), which act as probes traversing each path to confirm integrity. Upon detecting signal degradation or link loss, the protection logic triggers an immediate switchover. The key advantage lies in its hardware-based implementation, which circumvents software latency and guarantees deterministic behavior under stress conditions.

Types of Protection Schemes

EPT can be implemented using several architectures, each tailored to different topological and service requirements. The most prevalent forms include 1:1 and 1+1 protection schemes.

In the 1:1 model, both working and protection paths are provisioned, but only one carries live traffic at any time. The other remains idle until a fault occurs. When a failure is detected, the control plane switches traffic to the alternate path. This configuration balances resource efficiency with performance assurance.

In the 1+1 model, identical traffic streams are transmitted simultaneously across both paths. The receiving node continuously monitors signal quality and selects the superior stream in real time. This method achieves near-zero switchover delay but consumes double the bandwidth, as both paths are fully utilized at all times. Despite the cost, it is preferred in mission-critical networks demanding absolute reliability.

A more complex variation, 1:N protection, allocates one protection link to safeguard multiple working links. This approach optimizes resource usage but introduces additional coordination overhead. Engineers must evaluate these trade-offs carefully when designing transport architectures under Nokia’s optical framework.

EPT State Machines and Control Logic

Central to EPT’s functionality is its state machine—a deterministic set of conditions and transitions that dictate protection behavior. Each node in an EPT pair operates a synchronized finite-state machine that continuously evaluates link conditions. Common states include Idle, Working Active, Protection Active, Signal Fail, and Forced Switch. Transitions occur in response to stimuli such as signal loss, administrative commands, or hold-off timers.

Hold-off timers prevent premature switching caused by transient fluctuations, ensuring stability. Reversion timers, conversely, control whether traffic automatically returns to the primary path once it is restored. The balance between immediate restoration and stable operation defines the sophistication of EPT’s logic, underscoring why mastery of timing mechanisms is critical for achieving optimal performance.

Coordination with Operations, Administration, and Maintenance (OAM)

EPT is intrinsically linked to Ethernet OAM frameworks. It leverages OAM tools to detect, verify, and isolate faults within the data plane. OAM operates as the sensory system of EPT, providing the intelligence required for proactive fault detection. Mechanisms such as Loopback Messages (LBMs), Link Trace Messages (LTMs), and CCMs work collectively to ensure that every segment of the transport path remains observable and traceable.

The integration between EPT and OAM ensures not only rapid protection switching but also transparent fault localization. When a defect arises, operators can pinpoint the affected segment within milliseconds, enabling rapid restoration and minimizing mean time to repair. This synergy exemplifies how monitoring and protection complement one another in a modern transport network.

Advantages and Design Philosophy

The strength of EPT lies in its simplicity and predictability. By maintaining pre-provisioned paths and continuous synchronization, it eliminates the need for complex recalculation during failures. Recovery occurs locally at the nodes involved, without involving external control systems. This decentralized design ensures scalability across large networks with minimal signaling overhead.

Moreover, EPT provides a deterministic recovery time independent of network size or topology. Whether deployed across metropolitan rings or point-to-point backbone segments, its performance remains consistent. This characteristic is essential for carrier networks that support real-time applications such as voice, video, and financial transactions.

From a design standpoint, EPT aligns with the philosophy of graceful degradation. Instead of collapsing under failure, the network maintains service continuity through an alternate path, preserving quality of experience. Such resilience transforms optical infrastructures into living systems capable of adapting dynamically to adversity.

Deployment Scenarios in Optical Networks

EPT finds extensive application in transport environments where Ethernet serves as the service or aggregation layer atop optical infrastructure. It operates effectively in conjunction with WDM systems, enabling simultaneous wavelength diversity and Ethernet protection. For instance, each wavelength channel in a DWDM system can host an EPT session, ensuring both optical and logical resilience.

In metropolitan environments, EPT is commonly deployed in ring or mesh topologies. In ring configurations, protection switching can reroute traffic around a failed segment without disrupting other connections. In mesh designs, multiple redundant paths enable even more granular fault management. Such topological versatility ensures that EPT adapts seamlessly to both small and large-scale deployments.

When integrated with optical equipment such as Nokia’s 1830 Photonic Service Switch, EPT extends the resilience of the physical layer into the service domain. This convergence of optical and Ethernet protection mechanisms exemplifies the principle of end-to-end survivability—a hallmark of advanced transport design.

Performance Considerations and Limitations

While EPT offers exceptional reliability, it is not without limitations. The deterministic switching process requires precise synchronization and uniform link characteristics. Variations in latency, bandwidth, or propagation delay between working and protection paths can lead to packet reordering or transient jitter during switching. Engineers must therefore ensure path symmetry to uphold performance expectations.

Additionally, the resource duplication inherent in protection schemes increases capital expenditure. Effective network design seeks equilibrium between protection coverage and cost efficiency. Techniques such as shared protection and path diversity optimization mitigate these concerns while maintaining high availability. Balancing economics with engineering precision defines the art of EPT deployment.

Management and Control Integration

In a modern optical transport environment, EPT does not operate in isolation. It is supervised and orchestrated through advanced management systems that provide centralized visibility and configuration control. The Network Functions Manager for Transport, commonly referred to as NFM-T, plays a pivotal role in this orchestration. It allows operators to configure protection groups, monitor health indicators, and automate switchover operations through intuitive graphical interfaces.

The integration of EPT with such management platforms ensures operational consistency across heterogeneous network layers. Fault events in the Ethernet plane can be correlated with optical impairments in the underlying layer, enabling holistic diagnostics. This cross-layer coordination represents the next step in converged network management, where abstraction and automation replace manual intervention.

Testing and Validation Practices

Before full-scale deployment, EPT mechanisms must undergo rigorous validation to ensure that protection triggers function as expected under all conditions. Engineers simulate link failures, latency spikes, and asymmetrical path behavior to evaluate switching accuracy. Performance metrics such as switchover time, packet loss ratio, and hitless restoration define the quality benchmarks for certification.

Continuous monitoring after deployment remains equally critical. Alarms, threshold counters, and OAM statistics provide the empirical evidence necessary to maintain network integrity. Proper testing transforms theoretical protection into tangible resilience, reinforcing the confidence that carriers and enterprises place in Ethernet transport infrastructures.

Interoperability and Standardization

EPT adheres to globally recognized frameworks established by the ITU-T and IEEE. These standards ensure interoperability among devices from different vendors and guarantee consistent behavior across diverse infrastructures. Standardized message formats, state transitions, and recovery thresholds enable predictable operation even in multi-vendor environments.

This universality underscores why EPT remains relevant in heterogeneous networks. It allows operators to integrate legacy systems with new platforms while maintaining a unified protection model. The continuity between generations of technology ensures that networks evolve without sacrificing dependability.

The Strategic Role of EPT in Network Evolution

As transport networks transition toward software-defined paradigms, the foundational concepts of EPT continue to hold significance. While virtualized control layers automate path computation, the deterministic protection logic of EPT remains essential for real-time fault recovery. The synergy between static protection and dynamic orchestration forms the basis for future-ready optical architectures.

EPT exemplifies the timeless principle that resilience cannot rely solely on centralized intelligence. Even in programmable networks, local protection mechanisms provide the immediate reaction required to prevent catastrophic service disruption. This duality—instantaneous local recovery complemented by centralized optimization—defines the architecture of modern optical networks.

Understanding NFM-T in Optical Network Management

In modern optical transport systems, where vast layers of packet and photonic technologies converge, manual configuration and fragmented management are no longer sustainable. Network Functions Manager for Transport, or NFM-T, emerges as a cohesive management platform that unifies the monitoring, provisioning, and control of optical and Ethernet domains. For anyone preparing for the Nokia 4A0-205 Optical Networking Fundamentals exam, mastering NFM-T means understanding how network orchestration evolves from simple supervision to intelligent automation.

The Purpose and Philosophy of NFM-T

NFM-T is designed to streamline the complex task of managing transport networks that integrate multiple technologies such as WDM, OTN, and Ethernet. Its central purpose is to abstract the underlying complexity of physical and logical layers into an intuitive, policy-driven interface. In essence, it acts as the brain of the network—coordinating thousands of interconnected devices, links, and services through a unified operational environment.

Traditional network management systems often operated in silos, with separate tools for optical layers, IP layers, and service provisioning. NFM-T consolidates these into a single architectural entity, allowing operators to view and control the entire topology from a centralized console. This holistic perspective is vital for ensuring that performance, capacity, and reliability remain synchronized across diverse network elements.

Architecture and Core Components

NFM-T follows a modular architecture composed of several integral components. The main modules include the Element Manager, the Network Manager, and the Service Manager. Each performs a distinct function while maintaining interdependency through a central data repository.

The Element Manager communicates directly with individual network elements, gathering telemetry, alarms, and performance statistics. The Network Manager aggregates this data to construct a comprehensive view of the entire network topology, while the Service Manager translates high-level service requests into executable provisioning actions. This multi-tiered design allows granular control while preserving scalability for large networks encompassing thousands of nodes.

A database known as the Configuration Management Repository stores the operational state and configuration data of all managed entities. This repository acts as the single source of truth, ensuring that configuration consistency is maintained even across distributed deployments. By adhering to this architectural discipline, NFM-T achieves both operational coherence and rapid fault recovery.

Integration with Optical and Ethernet Layers

NFM-T’s strength lies in its ability to transcend technological boundaries. In an optical network, it interfaces seamlessly with photonic systems such as the Nokia 1830 Photonic Service Switch, enabling control over wavelength provisioning, amplifier settings, and optical channel monitoring. In the Ethernet layer, it manages services, protection groups, and link aggregation, providing a consistent management framework across domains.

This integration creates a hierarchical control structure where optical resources provide the foundation, and Ethernet or IP services operate above them. When faults or degradations occur at the physical layer, NFM-T propagates the information upward, allowing higher layers to adapt dynamically. This vertical visibility prevents cascading failures and facilitates rapid troubleshooting, a concept known as cross-layer correlation.

Fault Management and Alarm Processing

Effective fault management forms the cornerstone of NFM-T’s operational design. The system collects and categorizes alarms from every managed entity, filtering them through predefined severity levels such as critical, major, minor, and warning. These alarms are visualized through graphical dashboards, allowing operators to grasp network health at a glance.

Beyond simple alarm aggregation, NFM-T employs root cause analysis algorithms that distinguish between primary and consequential alarms. For instance, if a fiber cut triggers multiple downstream link failures, the system identifies the initial cause and suppresses redundant notifications. This intelligent filtering reduces operator fatigue and accelerates repair actions. Acknowledgment mechanisms allow teams to track incident handling progress, ensuring accountability and procedural discipline.

Configuration and Provisioning Workflows

One of the defining features of NFM-T is its capacity for automated provisioning. Rather than configuring devices individually, operators can define end-to-end services through templates and workflows. The system translates these abstract service definitions into precise configuration commands for each network element involved.

This automation eliminates human error and dramatically reduces provisioning time. When establishing an optical circuit, for example, NFM-T determines the optimal wavelength, configures the required amplifiers, and synchronizes settings across multiple nodes. The same principle applies to Ethernet services, where it automatically assigns VLANs, protection paths, and Quality of Service parameters.

Provisioning tasks can also be scheduled or triggered dynamically in response to network events. Such adaptability makes NFM-T an essential instrument for achieving operational agility in high-capacity transport networks.

Performance and Quality Management

NFM-T provides continuous monitoring of performance metrics to ensure that network services meet predefined Service Level Agreements. Key indicators such as optical power, bit error rate, latency, and throughput are measured and archived for trend analysis. These metrics enable predictive maintenance, allowing operators to anticipate degradation before it leads to failure.

The system visualizes performance through graphs and dashboards, where threshold crossings automatically trigger alarms. This proactive management philosophy transforms traditional reactive maintenance into a forward-looking practice rooted in empirical data. The ability to correlate performance anomalies with specific network components allows precise interventions, optimizing both efficiency and reliability.

Security and Access Control Mechanisms

In an era of escalating cyber threats, network management systems must enforce rigorous security controls. NFM-T implements a multi-layered security framework encompassing authentication, authorization, and encryption. User roles define access privileges, ensuring that configuration rights align with operational responsibilities. For instance, a technician may view alarms but lack the authority to modify service parameters.

The system also supports secure communication protocols for device management, including SSH and SNMPv3, ensuring that configuration data remains protected during transmission. Logging mechanisms record every user action, creating an immutable audit trail that enhances accountability and compliance with regulatory standards. Security is not an afterthought in NFM-T—it is an inherent component of its architectural integrity.

Data Correlation and Visualization

NFM-T transforms raw operational data into actionable intelligence through advanced visualization techniques. Network maps display topological relationships between nodes, links, and services. These maps are dynamic, updating in real time to reflect changes such as path reconfigurations or node failures.

Correlation engines analyze this data to reveal hidden dependencies and performance patterns. By correlating optical signal strength with Ethernet throughput, for instance, the system can pinpoint cross-layer inefficiencies that would otherwise remain obscure. Such analytical depth empowers operators to move beyond reactive management and engage in continuous optimization.

Automation and Policy-Based Control

One of the defining evolutions introduced by NFM-T is policy-driven automation. Instead of manually enforcing operational rules, operators define policies that dictate how the network should behave under specific conditions. These policies may involve rerouting traffic, allocating additional capacity, or adjusting optical power levels. Once configured, NFM-T enforces them autonomously, ensuring consistent decision-making across the network.

Policy-based control introduces a new paradigm in network operations: intent-based management. Operators articulate desired outcomes, and the system translates them into executable instructions. This abstraction allows engineers to focus on strategy rather than minutiae, dramatically enhancing efficiency and scalability in large networks.

Scalability and Distributed Deployment

As networks expand geographically and technologically, scalability becomes a pivotal concern. NFM-T supports distributed deployment architectures where management functions are spread across multiple servers to accommodate increasing load. This design not only enhances performance but also provides redundancy against system failures.

The distributed model enables regional control centers to operate semi-autonomously while synchronizing with a central management core. This hierarchical arrangement mirrors the structure of large service provider organizations, aligning operational control with physical geography. It ensures that even as networks grow in scale and complexity, management responsiveness remains intact.

Integration with Other Network Layers

NFM-T’s integration extends beyond transport and Ethernet domains to interface with IP and MPLS layers. This interoperability allows coordinated provisioning of end-to-end services across multi-technology environments. When a new IP service is created, for example, NFM-T ensures that the underlying optical and Ethernet paths are already provisioned and healthy. Such orchestration prevents configuration conflicts and guarantees consistent quality across the entire service chain.

Furthermore, by integrating with higher-level orchestration platforms, NFM-T contributes to the automation of hybrid networks that combine physical and virtual functions. This convergence embodies the ongoing transformation toward software-defined infrastructure, where management systems act as the cohesive fabric binding diverse network elements together.

Maintenance and Lifecycle Management

The maintenance philosophy embedded in NFM-T extends beyond fault detection to encompass complete lifecycle management. From deployment and configuration to upgrade and decommissioning, every phase of a network element’s existence is tracked and recorded. Software version management ensures that all devices maintain compatibility, while rollback mechanisms allow recovery from erroneous updates.

Scheduled backups of configuration data guarantee resilience against database corruption or system failure. Lifecycle analytics, meanwhile, assess resource utilization trends to guide capacity planning and investment strategies. This long-term perspective elevates network management from daily operation to strategic governance.

The Role of NFM-T in Network Transformation

As operators migrate toward virtualized and cloud-centric environments, NFM-T remains an indispensable bridge between legacy and modern infrastructures. Its design supports hybrid operation, where traditional hardware-based elements coexist with software-defined components. Through open interfaces and standardized protocols, NFM-T enables smooth evolution without necessitating wholesale replacement of existing assets.

The system’s ability to manage both physical and virtualized functions foreshadows the future of transport management, where programmability and analytics merge into an autonomous operational paradigm. By embedding intelligence at the control layer, NFM-T transforms optical networks into adaptive ecosystems that respond dynamically to user demand and network conditions.

Optical Network Design and Implementation Concepts

The design and implementation of optical networks form the structural essence of modern communication systems. It is through meticulous design principles that optical infrastructures achieve the resilience, scalability, and capacity required to sustain global data exchange. For those preparing for the Nokia 4A0-205 Optical Networking Fundamentals exam, understanding how optical design principles interconnect physical realities with logical intentions is pivotal. Optical networks, by their very nature, demand both scientific precision and architectural artistry.

Foundations of Optical Network Design

Designing an optical network begins with a fundamental understanding of the service requirements it must fulfill. Capacity, reach, latency, availability, and scalability serve as the primary dimensions shaping architectural choices. Engineers must translate these parameters into quantifiable design objectives. The goal is to create a system capable of transmitting enormous quantities of data with minimal latency and near-perfect reliability.

Optical design follows a hierarchical approach. At the lowest level, the fiber infrastructure defines physical connectivity. Above this lies the optical layer, which manages wavelengths and signal propagation. The upper layers include transport and service domains, responsible for logical path management and service delivery. The synchronization among these layers forms the foundation for coherent design.

Network Topologies and Their Strategic Implications

Topology determines how optical nodes and links interconnect, influencing both performance and resilience. Common topologies include point-to-point, ring, mesh, and hybrid structures. Each offers distinct operational advantages and constraints.

Point-to-point configurations are simple and efficient for dedicated links, often used for data center interconnections or backhaul transport. However, their lack of redundancy makes them unsuitable for high-availability networks. Ring topologies, in contrast, provide inherent protection through alternate routing, allowing traffic to bypass faults via the opposite direction. This design balances simplicity with reliability, making it popular in metropolitan transport networks.

Mesh topologies represent the pinnacle of flexibility and survivability. Multiple paths exist between nodes, enabling dynamic rerouting and optimal resource utilization. Although mesh networks offer superior resilience, they require sophisticated control mechanisms to manage wavelength assignment and path optimization. Hybrid architectures often combine these models, merging the efficiency of rings with the adaptability of mesh frameworks.

Link Budget Analysis and Power Balancing

The link budget constitutes the quantitative backbone of optical design. It accounts for every gain and loss encountered by an optical signal as it travels through the network. Engineers calculate the total available optical power from the transmitter and subtract cumulative losses introduced by fibers, connectors, splices, and passive components. The remaining power margin determines whether a signal can reach its destination without regeneration.

Optical amplifiers extend reach by compensating for attenuation, but they must be carefully balanced to prevent saturation or noise amplification. Excessive power may induce nonlinear effects, while insufficient power compromises signal detectability. Maintaining equilibrium among these variables requires iterative refinement, ensuring that every optical span remains within operational thresholds.

Dispersion management complements power budgeting by preserving signal integrity. Techniques such as dispersion-compensating modules, coherent detection, and electronic equalization mitigate pulse broadening, which can distort high-speed signals. Mastery of these calculations distinguishes a proficient network designer from a merely competent one.

Wavelength Planning and Channel Allocation

Efficient wavelength planning ensures optimal utilization of available spectrum while minimizing interference. The International Telecommunication Union’s frequency grid defines standardized intervals for dense wavelength division multiplexing. Engineers select channel spacing based on desired capacity and spectral efficiency. Narrow spacing enhances capacity but demands high filter precision and temperature stability.

Channel allocation strategies must also consider amplifier gain profiles and non-linear impairments. Uneven optical power among channels, known as tilt, can degrade performance. Equalization techniques and variable optical attenuators are employed to maintain uniformity. The ability to harmonize these spectral elements demonstrates not only technical skill but also an intuitive grasp of photonic equilibrium.

Dynamic wavelength assignment adds an additional layer of complexity. In reconfigurable optical networks, wavelengths may be reassigned based on traffic demands. Automation platforms such as NFM-T facilitate this by adjusting channel configurations in real time. Thus, wavelength planning evolves from static design to adaptive orchestration.

Protection and Restoration Strategies

Reliability stands at the heart of every optical design philosophy. Protection mechanisms ensure continuity when faults occur. Common approaches include line protection, path protection, and shared mesh protection. Line protection operates at the physical level, rerouting traffic around faulty fiber spans. Path protection functions at a logical level, redirecting end-to-end services through pre-established alternate routes.

Shared mesh protection maximizes efficiency by allowing multiple working paths to share the same protection resources. When a fault occurs, only the affected traffic occupies the protection route, leaving others unaffected. This intelligent resource sharing exemplifies the convergence of resilience and efficiency.

Restoration mechanisms extend beyond static protection. While protection provides immediate recovery through preplanned paths, restoration dynamically recalculates routes after failure detection. This adaptability is particularly beneficial in large-scale networks where flexibility outweighs reaction speed. Together, protection and restoration ensure that optical infrastructures maintain continuity under all conceivable conditions.

Amplification and Regeneration Planning

Optical signals degrade as they traverse long distances, necessitating periodic amplification. The placement and configuration of amplifiers such as Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers and Raman amplifiers play a critical role in sustaining signal quality. Engineers determine amplifier spacing based on loss budgets and noise accumulation.

Regeneration, though less frequent in modern coherent systems, remains essential in ultra-long-haul designs. Regenerative sites restore signal shape, timing, and power. However, they introduce cost and complexity, so designers aim to minimize their number through advanced modulation formats and optimized dispersion control. Amplification and regeneration planning, therefore, balance physics with economics—a recurring theme in optical engineering.

Node and Equipment Configuration

Network nodes, often embodied as reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers, serve as the convergence points for wavelength routing and service interconnection. Proper configuration of these nodes determines the agility and scalability of the network. Each node contains wavelength-selective switches that direct optical channels to desired paths without optical-electrical conversion. This all-optical switching paradigm reduces latency and power consumption.

Incorporating redundant control planes within node architecture enhances fault tolerance. Even if one controller fails, operations continue seamlessly under the backup unit. Modular design principles further enable incremental capacity upgrades, allowing networks to evolve alongside traffic demands. The sophistication of node configuration directly influences the adaptability of the entire system.

Synchronization and Latency Considerations

High-capacity transport networks depend heavily on synchronization, especially in environments supporting time-sensitive applications. Precise timing ensures that packets and optical channels align correctly across multiple layers. Synchronization can be derived through protocols like Synchronous Ethernet or Precision Time Protocol, ensuring microsecond-level accuracy.

Latency, the temporal delay between transmission and reception, influences service performance, particularly for applications like high-frequency trading or 5G backhaul. Optical design minimizes latency through efficient routing, low-dispersion fiber, and optimized amplification intervals. Striking harmony between latency control and protection mechanisms reflects a designer’s ability to reconcile competing priorities.

Implementation Planning and Commissioning

Transitioning from design to implementation requires systematic planning and coordination. Physical deployment begins with fiber installation, connector inspection, and power calibration. Engineers validate link performance through optical time-domain reflectometry and power level verification. These steps ensure that the network meets design specifications before service activation.

Commissioning also involves configuring management interfaces and verifying communication between network elements and control systems. Automation tools streamline this process, reducing human intervention and ensuring consistency. Documentation at each stage preserves transparency, forming the foundation for future maintenance and upgrades.

Testing and Validation Procedures

Testing validates the theoretical integrity of a design under real-world conditions. Engineers perform optical power measurements, bit error rate tests, and latency verification across all links. Stress testing subjects the network to failure simulations to ensure that protection mechanisms respond within expected thresholds. These tests expose potential weaknesses before live operation begins.

Performance baselines are established during validation, enabling continuous comparison throughout the network’s lifecycle. Such baselines serve as reference points for troubleshooting and performance optimization. Rigorous testing not only certifies functionality but also instills confidence in the network’s operational endurance.

Documentation and Change Management

Comprehensive documentation serves as the intellectual repository of network knowledge. Diagrams, configuration files, and parameter records ensure transparency and traceability. Change management processes govern any modifications, whether physical or logical. Before implementing a change, engineers analyze its potential impact on existing services, reducing the risk of unintended disruptions.

Automated management systems integrate with documentation frameworks to maintain up-to-date inventories. Each network element’s attributes, firmware versions, and performance history are preserved. This meticulous record-keeping transforms complexity into clarity, supporting long-term stability and compliance.

Challenges and Emerging Trends in Design

Modern optical design faces new challenges as data consumption accelerates and service expectations rise. Traffic patterns have become unpredictable, driven by cloud computing, streaming, and artificial intelligence workloads. Designers must anticipate fluctuating capacity demands and integrate elasticity into the network’s DNA. Technologies like flexible-grid WDM and sliceable bandwidth allocation enable this adaptability.

Another transformative trend involves the convergence of optical and packet layers under unified control frameworks. Software-defined networking extends programmability into the optical domain, allowing real-time optimization of wavelengths and bandwidth. Artificial intelligence further enhances predictive design by analyzing historical data to forecast network behavior. These advancements redefine the boundaries of optical architecture.

Optical Network Performance, Monitoring, and Troubleshooting

The stability and dependability of any optical transport network depend upon the meticulous evaluation of its performance and the precision of its monitoring systems. As optical infrastructures evolve into highly dynamic and dense environments, continuous supervision becomes indispensable. Performance management ensures that signals traverse fibers without degradation, while troubleshooting mechanisms restore harmony when disruptions arise. For candidates pursuing the Nokia 4A0-205 Optical Networking Fundamentals certification, mastering the philosophy and practice of optical performance monitoring is central to understanding how operational excellence is maintained in high-capacity systems.

The Essence of Performance Management

Performance management in optical networks refers to the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of operational data to ensure the network adheres to defined service standards. It encompasses parameters that quantify signal health, latency, throughput, and error rates. By transforming raw measurements into actionable intelligence, operators can identify early signs of degradation before they escalate into service outages.

Unlike reactive maintenance, performance management thrives on foresight. Its primary objective is to preserve signal integrity and service continuity by predicting impairments rather than merely reacting to them. This predictive nature elevates the optical network from a static infrastructure into a self-aware ecosystem governed by real-time analytics.

Key Parameters Influencing Optical Performance

A multitude of parameters influence the operational quality of optical transmission. Optical power levels, chromatic dispersion, polarization mode dispersion, and optical signal-to-noise ratio collectively define the fidelity of light as it journeys through the fiber. Each parameter interacts subtly with the others, creating a delicate equilibrium that must be constantly maintained.

Optical power represents the most fundamental metric. Insufficient power weakens the signal, increasing bit errors, while excessive power induces nonlinearities that distort the waveform. Chromatic dispersion causes pulse broadening, where different wavelengths travel at slightly varying speeds. Polarization mode dispersion introduces random delays between polarization states, especially significant at higher bit rates. Meanwhile, a low optical signal-to-noise ratio reflects amplifier noise accumulation and optical crosstalk.

By observing and correlating these parameters, engineers derive a comprehensive picture of network health. The interdependence of these factors underscores the need for holistic monitoring rather than isolated inspection.

Tools and Techniques for Optical Performance Monitoring

Modern optical systems employ a sophisticated arsenal of monitoring tools to measure and interpret performance parameters. Optical Time Domain Reflectometers (OTDRs) remain a cornerstone technology, providing spatially resolved insights into fiber loss, reflections, and splices. They emit light pulses and analyze the backscattered signal, revealing the location and magnitude of anomalies along the fiber span.

Optical spectrum analyzers complement this by evaluating spectral characteristics. They display the distribution of power across wavelengths, exposing issues such as channel imbalance or crosstalk. Bit Error Rate Testers (BERTs) assess the accuracy of transmitted data by comparing received bits against a known pattern, providing an exact quantification of transmission quality.

Performance monitoring modules embedded within network elements continuously report parameters like optical power, wavelength drift, and signal quality indicators. These metrics feed into centralized management platforms such as NFM-T, which aggregates and visualizes data for human interpretation. The fusion of hardware instrumentation and software analytics embodies the principle of intelligent supervision.

Proactive Monitoring and Predictive Analytics

Proactive monitoring transcends basic observation by incorporating predictive analytics. Through statistical trend analysis and machine learning models, anomalies can be anticipated before service degradation becomes noticeable. Predictive systems analyze long-term variations in optical power, temperature fluctuations, and historical failure patterns to estimate the probability of future faults.

This predictive capability transforms operational philosophy from reactive repair to preventive optimization. For example, if an amplifier’s gain slowly drifts from its nominal value, predictive algorithms can trigger pre-emptive recalibration before customer impact occurs. Such foresight ensures that service reliability remains uncompromised, reflecting the industry’s gradual shift toward autonomous network maintenance.

Quality of Transmission and Bit Error Analysis

Quality of Transmission, or QoT, serves as the ultimate indicator of optical link performance. It encompasses metrics such as Q-factor, Bit Error Rate (BER), and Error Vector Magnitude. These parameters quantify how faithfully data is represented at the receiver compared to the transmitter. BER analysis, in particular, provides a direct correlation between signal impairments and user experience.

In high-speed optical networks, Forward Error Correction (FEC) techniques compensate for inevitable errors by adding redundancy to the transmitted signal. Monitoring post-FEC and pre-FEC BER values enables engineers to distinguish between transient impairments and structural issues. A growing disparity between these values often signals progressive deterioration, warranting investigation. By meticulously analyzing error patterns, operators can pinpoint whether impairments stem from dispersion, non-linear distortion, or hardware misalignment.

Alarm and Fault Management Framework

A well-structured alarm management framework forms the operational nervous system of an optical network. Every monitored parameter has defined thresholds that trigger alarms when exceeded. These alarms are categorized by severity—ranging from warnings that indicate potential risks to critical alerts demanding immediate intervention. Prioritization ensures that vital issues receive prompt attention, preventing minor anomalies from overwhelming operators.

Alarms are not merely notifications; they are the language through which the network communicates its condition. Intelligent alarm correlation eliminates redundancy by grouping related events under a single root cause. This refinement minimizes noise and enhances focus. Integration with platforms like NFM-T allows these alarms to be visualized, acknowledged, and tracked through their resolution lifecycle. Such systematization embodies the discipline of structured troubleshooting.

Stepwise Troubleshooting Methodology

Troubleshooting in optical environments requires a blend of analytical reasoning and empirical testing. The process typically follows a sequential methodology: symptom identification, isolation, root cause analysis, correction, and verification. This systematic approach prevents hasty conclusions and ensures that every corrective action aligns with underlying causes.

The first step involves observing alarms, logs, and performance metrics to detect anomalies. Isolation narrows the focus to a specific segment or component, often verified through targeted OTDR tests or power measurements. Root cause analysis explores the physical or logical reason behind the fault—whether it be a connector contamination, fiber bend, amplifier drift, or wavelength misconfiguration. Once corrected, verification confirms the restoration of normal operation through comparative testing. The discipline of stepwise troubleshooting transforms complex network failures into solvable puzzles of precision.

Common Optical Faults and Their Resolution

Optical networks, though resilient, are susceptible to a variety of faults. Fiber cuts remain one of the most disruptive events, typically caused by external construction or environmental stress. Detecting such breaks relies on real-time loss-of-signal alarms and OTDR trace analysis. Rapid restoration is achieved through rerouting mechanisms and preconfigured protection paths.

Connector contamination constitutes another prevalent issue. Dust or oil residues at connector interfaces can introduce reflection losses or intermittent attenuation. Routine inspection and cleaning are therefore critical. Misalignment of optical modules can similarly degrade performance, requiring calibration or replacement. Amplifier saturation, wavelength drift, and polarization instability represent more subtle failures that demand nuanced diagnosis. Each fault type reinforces the need for comprehensive monitoring frameworks capable of distinguishing between physical and systemic anomalies.

Performance Baselines and Trend Analysis

Establishing performance baselines forms an essential part of operational stability. Baselines define the expected behavior of optical parameters under normal conditions. By continuously comparing real-time data against these benchmarks, deviations can be detected instantly. Trend analysis extends this practice by examining long-term variations, enabling recognition of gradual deterioration patterns.

For example, a slow decline in optical power might indicate fiber aging or connector degradation, while a periodic fluctuation could signal environmental influence such as temperature variation. Maintaining accurate baselines ensures that troubleshooting begins with context rather than conjecture. The combination of baselines and trend analytics empowers operators to manage networks with scientific precision.

Integration of Monitoring with Management Systems

Performance and fault data hold limited value without a unifying management framework. Platforms like NFM-T assimilate this data from various network layers, presenting it through a coherent graphical interface. Operators can visualize link states, optical power levels, and alarm statuses in real time. Correlation algorithms match events across layers, revealing causal relationships between optical impairments and higher-layer service disruptions.

Automation features extend this integration by allowing preprogrammed responses to specific triggers. For instance, a detected drop in optical power might automatically activate protection switching or initiate diagnostic scripts. Such coordination minimizes human latency and strengthens overall reliability. Through the union of monitoring and management, optical networks achieve cognitive operational behavior.

Maintenance and Preventive Strategies

Effective maintenance transcends routine inspection; it encompasses a comprehensive strategy combining periodic testing, calibration, and component replacement. Scheduled maintenance windows allow engineers to perform fiber cleaning, firmware upgrades, and equipment validation without impacting active services. Predictive analytics further refine maintenance schedules by identifying components approaching end-of-life or performance degradation.

Preventive strategies also involve environmental conditioning. Controlling humidity, temperature, and dust accumulation within optical facilities prolongs equipment lifespan. Proper cable routing and strain relief prevent mechanical stress that could compromise fiber integrity. Maintenance thus becomes an ongoing dialogue between human diligence and machine intelligence.

The Role of Automation in Troubleshooting

Automation has revolutionized troubleshooting by embedding diagnostic intelligence directly into the network. Self-diagnostic modules continuously evaluate internal metrics and trigger automatic corrective actions. For example, if an amplifier detects output power drift, it can recalibrate its gain autonomously. In multi-layer architectures, automated fault correlation identifies the precise layer where degradation originates, sparing engineers from exhaustive manual tracing.

Artificial intelligence enhances this automation further. Machine learning models trained on historical fault data can predict failure signatures, recommend corrective measures, and even execute recovery scripts. This convergence of automation and analytics exemplifies the shift toward self-healing networks—systems that detect, diagnose, and recover with minimal human intervention.

Testing for Compliance and Quality Assurance

Testing for compliance ensures that network performance aligns with industry standards and contractual obligations. Optical systems are often subjected to acceptance testing that verifies their conformity with specifications. These tests validate optical power, signal quality, and restoration times under controlled conditions. Documenting results provides verifiable evidence of network readiness.

Quality assurance extends beyond initial deployment, encompassing continuous adherence to performance metrics throughout the network’s lifespan. Regular audits confirm that configurations, firmware versions, and operational parameters remain consistent. This disciplined approach transforms maintenance from a reactive task into an institutionalized process of perpetual improvement.

Future Trends and Innovations in Optical Networking

The trajectory of optical networking continues to ascend, shaped by relentless demand for bandwidth, agility, and intelligence. What began as the quest to transmit light through glass fibers has evolved into a sophisticated symbiosis between photonics, computation, and automation. Future optical systems will not only transport information but also interpret, optimize, and adapt dynamically to evolving digital ecosystems. Understanding the emerging directions in optical innovation is essential for grasping where the next generation of networks—and the professionals who design them—are heading.

Evolution of Capacity and Spectral Efficiency

At the heart of future optical advancements lies the continuous drive to expand capacity. The traditional approach of simply increasing channel counts within the C-band has reached physical limits. Engineers now pursue spectral expansion into the L-band and even the S-band, effectively doubling usable frequency space. Beyond that, elastic optical networks exploit variable channel widths and flexible grids to optimize spectral occupancy.

The concept of spectral efficiency—maximizing bits per hertz—remains a guiding objective. Advanced modulation formats such as 64-QAM and probabilistic constellation shaping extract more information from each photon. Coherent detection, coupled with digital signal processing, enables precise control of phase and amplitude, pushing boundaries once thought unreachable. The result is a dramatic leap in data density, transforming single fibers into conduits capable of carrying petabit-scale capacities.

Integration of Photonic and Electronic Domains

Optical communication has traditionally relied on distinct domains for transmission and control: photonics for light propagation and electronics for processing. This separation is rapidly dissolving. Photonic integrated circuits are merging these realms onto single chips, allowing lasers, modulators, and detectors to coexist with electronic amplifiers and processors. This convergence reduces latency, power consumption, and cost while enhancing stability.

Silicon photonics exemplifies this paradigm. By leveraging semiconductor manufacturing processes, it enables mass production of compact, high-performance optical components. Such integration also paves the way for on-chip WDM systems, where entire transceivers can operate within a miniature form factor. These innovations promise not only scalability but also the democratization of high-speed optical technology across industries.

The Rise of Space Division Multiplexing

As wavelength and modulation innovations approach their theoretical limits, attention turns toward spatial multiplexing. Space Division Multiplexing (SDM) introduces multiple parallel paths within a single fiber, achieved through multi-core or few-mode designs. Each core or mode acts as an independent transmission channel, exponentially increasing total capacity without demanding additional fibers.

While SDM presents formidable challenges—such as inter-core crosstalk and complex amplification—it also holds extraordinary potential. Laboratories have already demonstrated multi-core fibers transmitting data rates exceeding several petabits per second. In practical deployments, SDM will enable hyperscale data centers, intercontinental backbones, and emerging cloud infrastructures to meet insatiable traffic growth without expanding physical footprints.

Flexibility Through Software-Defined Photonics

The principle of flexibility now extends deep into the optical layer. Software-defined photonics transforms static configurations into programmable environments. By abstracting control over wavelengths, modulation formats, and power levels, operators can dynamically allocate resources according to demand. Software-defined networking principles are being adapted to govern optical behaviors in real time.

Network elements equipped with reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers already embody this flexibility. Future iterations will evolve further, supporting fully autonomous wavelength reallocation and traffic balancing. Through integration with control systems such as NFM-T, software-defined photonics introduces unprecedented agility—enabling networks that morph fluidly with shifting service landscapes.

Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Networking

Artificial intelligence has begun to weave itself into every layer of optical infrastructure. Cognitive networking—an architecture where AI and machine learning continuously observe, predict, and adjust network behavior—marks the dawn of a new operational era. Algorithms analyze terabytes of telemetry, detecting latent patterns invisible to human operators. They forecast equipment aging, optimize optical power distribution, and propose configuration changes that sustain peak performance.

Predictive maintenance exemplifies this shift. By learning the subtle signatures that precede component failure, AI can initiate corrective measures autonomously, reducing downtime and operational expenditure. Reinforcement learning techniques extend this further by enabling the network to experiment and refine its strategies continuously. In cognitive optical systems, decision-making becomes distributed, adaptive, and profoundly intelligent.

Quantum Communication and Secure Transmission

Beyond classical optics lies the quantum frontier, where photons carry information encoded in quantum states rather than binary symbols. Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) harnesses the principles of quantum mechanics to enable theoretically unbreakable encryption. Any attempt to intercept or measure the photons alters their state, instantly revealing the presence of an intruder. As data security assumes paramount importance, quantum communication is poised to redefine trust in digital infrastructure.

Quantum channels can coexist with conventional data on the same fiber, provided isolation and synchronization are maintained. Researchers are developing hybrid systems that integrate QKD with existing optical frameworks, paving the path toward quantum-secured metropolitan and long-haul networks. For the future optical engineer, understanding quantum communication will soon become as essential as mastering dispersion or amplification today.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Optical Design

Sustainability has become a defining metric of technological progress. The exponential rise in data traffic has magnified the energy footprint of communication networks, compelling designers to innovate toward efficiency. Optical technologies naturally consume less energy per bit than electronic counterparts, yet opportunities for improvement abound.

Advancements in low-power lasers, intelligent cooling systems, and energy-aware routing algorithms collectively contribute to greener networks. Amplifier technologies are also evolving, with distributed Raman amplification offering lower noise and better power efficiency. Moreover, network virtualization and intelligent sleep modes reduce idle consumption during low traffic periods. The emerging philosophy of sustainable photonics intertwines ecological responsibility with engineering ingenuity.

Edge Optical Architectures and Cloud Convergence

The growing decentralization of computation has redefined network architecture. Edge computing brings data processing closer to users, reducing latency and bandwidth strain on core infrastructures. Optical networks must adapt by extending high-capacity links to edge nodes and micro data centers. This transformation demands compact optical modules, agile wavelength allocation, and seamless orchestration across multiple layers.

Cloud convergence amplifies this need. As hyperscale cloud providers deploy global infrastructures, optical transport becomes the connective tissue linking their distributed environments. Programmable optical fabrics, guided by platforms like NFM-T, ensure that cloud workloads move fluidly between locations with minimal delay. The synergy between optical transport and cloud architecture signals a profound evolution from connectivity to cohesion.

The Emergence of Multi-Layer Coordination

Future optical systems will not operate in isolation but as part of a unified multi-layer ecosystem. The optical, packet, and service layers will communicate bidirectionally, sharing state information to optimize resource utilization. A traffic surge detected at the packet layer could prompt optical bandwidth adjustments in real time, ensuring efficiency without human intervention.

This vision of integrated coordination aligns with the philosophy of intent-based networking, where operators define desired outcomes rather than explicit configurations. Automation frameworks interpret these intents, translating them into actions across all layers. Such orchestration ensures that performance, cost, and resilience remain balanced dynamically. Multi-layer coordination thus transforms networks from reactive mechanisms into intelligent organisms.

Optical Virtualization and Network Slicing

Virtualization has reshaped data centers and is now permeating optical transport. Optical network slicing enables multiple virtual optical networks to coexist over shared physical infrastructure. Each slice can possess its own performance parameters, isolation levels, and management policies. This flexibility allows operators to offer differentiated services—high-throughput channels for enterprises, ultra-low latency paths for financial institutions, and resilient connections for mission-critical applications.

Dynamic slicing relies on programmable transceivers and adaptive control planes. As bandwidth demands shift, slices expand or contract accordingly. This evolution introduces a business dimension to optical networking, transforming it from a static utility into a customizable service platform. The concept resonates deeply with future communication paradigms such as 6G and autonomous connectivity ecosystems.

Challenges on the Horizon

With innovation comes complexity. As optical systems grow more intelligent, their interactions become increasingly intricate. Managing thousands of adaptive elements, each responding to environmental stimuli, requires robust control architectures. Standardization must evolve to ensure interoperability across vendors and technologies. Moreover, the scarcity of skilled professionals capable of mastering both photonic principles and software automation poses a critical challenge.

Security also intensifies as networks gain programmability. Safeguarding control channels and ensuring trust among autonomous components become paramount. Future networks will need built-in mechanisms for authentication, verification, and anomaly detection at both optical and digital levels. The convergence of intelligence and automation demands not only technical precision but ethical foresight.

Educational and Professional Implications

As technology advances, so must the expertise of those who design and maintain it. The Nokia 4A0-205 certification embodies the foundational knowledge necessary to comprehend these evolving paradigms. Yet, the optical professional of the future will require multidisciplinary fluency—encompassing photonics, electronics, data science, and artificial intelligence. The capacity to interpret data, model behavior, and engineer adaptive systems will distinguish visionary engineers from routine operators.

Continuous education will become a perpetual necessity. With each technological leap, the vocabulary of networking expands, introducing new principles and methodologies. Staying aligned with these transformations demands curiosity, discipline, and a commitment to lifelong learning. Optical networking, once perceived as a specialized domain, is now a crucible for broader digital transformation.

The Horizon of Autonomy

Autonomy defines the endgame of future optical design—the creation of networks that configure, monitor, and optimize themselves. Through the interplay of AI, software-defined control, and photonic precision, such systems will achieve near-instantaneous adaptation to shifting conditions. They will route traffic intelligently, balance power dynamically, and repair themselves when faults occur. The human role will evolve from manual intervention to strategic oversight, guiding the network’s evolution rather than its minutiae.

This vision embodies a philosophical shift. Networks will cease to be static infrastructure and instead become sentient entities—fluid, learning, and continuously optimizing. The artistry of engineering will no longer reside solely in design, but in nurturing these self-organizing systems toward ever-greater harmony and resilience.

Conclusion

The exploration of optical networking through the lens of WDM, EPT, and NFM-T reveals a discipline where science, precision, and innovation converge. Each concept—whether it involves the multiplexing of wavelengths, the protection of transmission paths, or the intelligent management of network functions—embodies the intricate balance that sustains modern communication systems. Optical networks are no longer passive conduits of light; they have evolved into adaptive frameworks that learn, predict, and optimize in real time. Their future lies in integration—of photonics with software, of intelligence with automation, and of human ingenuity with machine precision. Mastering these principles, as required in the Nokia 4A0-205 Optical Networking Fundamentals, is not merely about technical competence but about perceiving the interconnected harmony that governs global connectivity. The continuing evolution of optical technologies will shape how the world communicates, collaborates, and innovates. To understand these systems is to understand the language of light itself—subtle, powerful, and transformative. Those who harness this understanding will illuminate the path toward faster, smarter, and more resilient networks that define the digital era’s enduring rhythm.