Certification: Certified Fraud Examiner - Investigation

Certification Full Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Investigation

Certification Provider: ACFE

Exam Code: CFE - Investigation

Exam Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Investigation

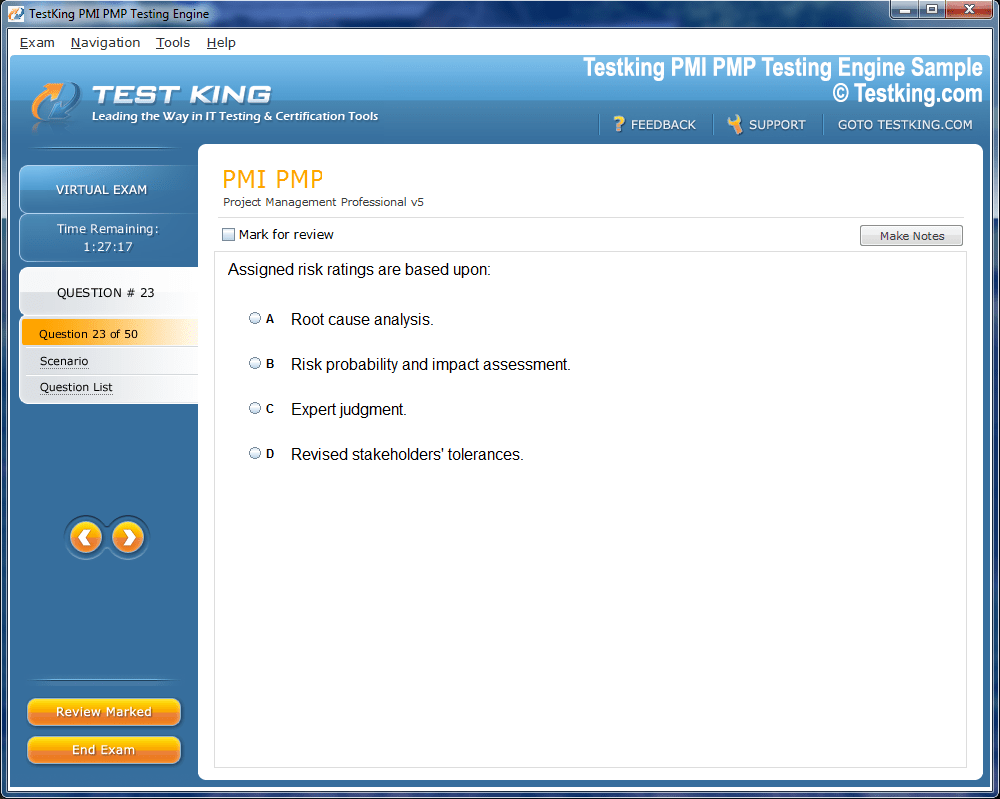

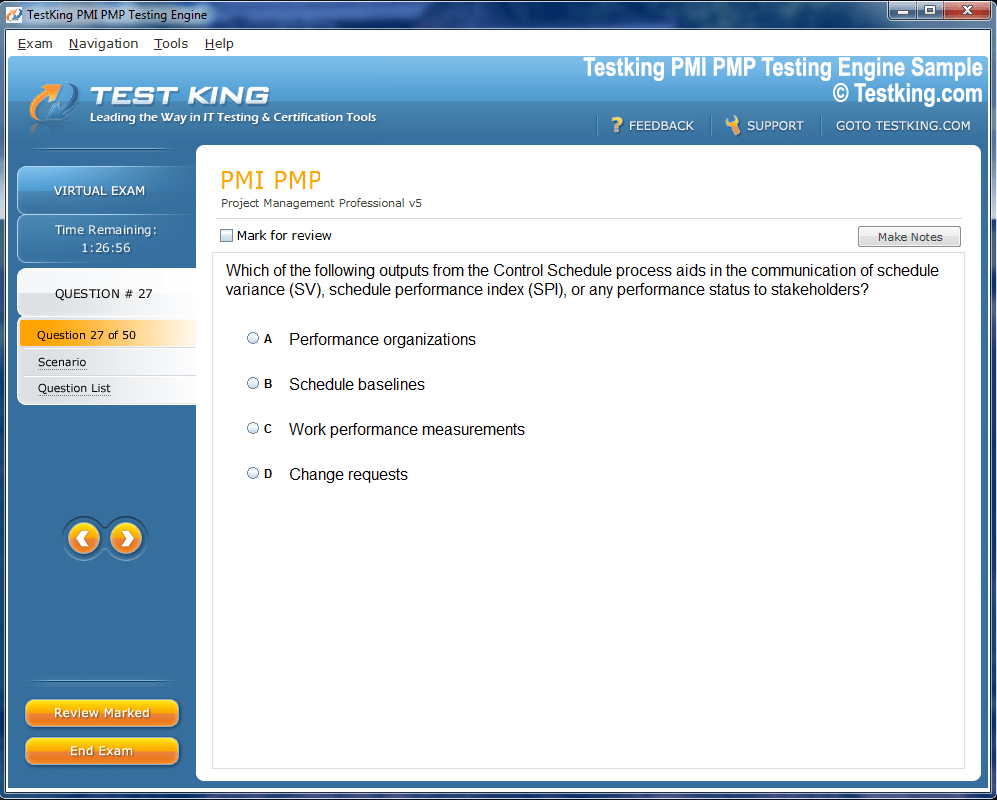

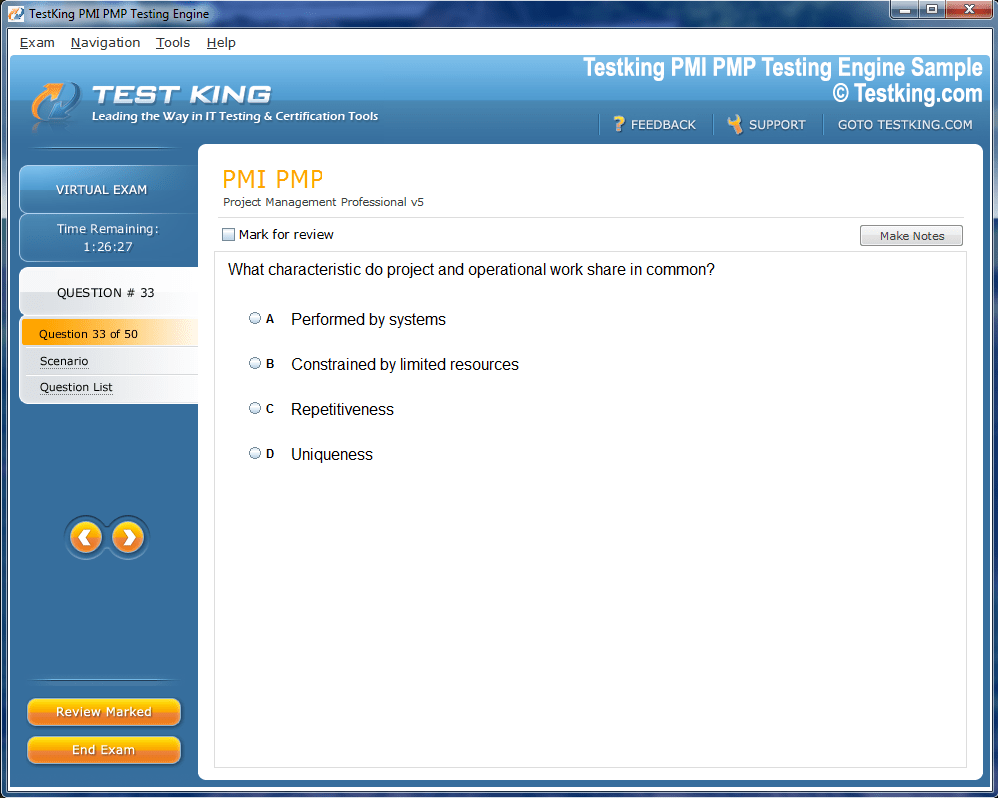

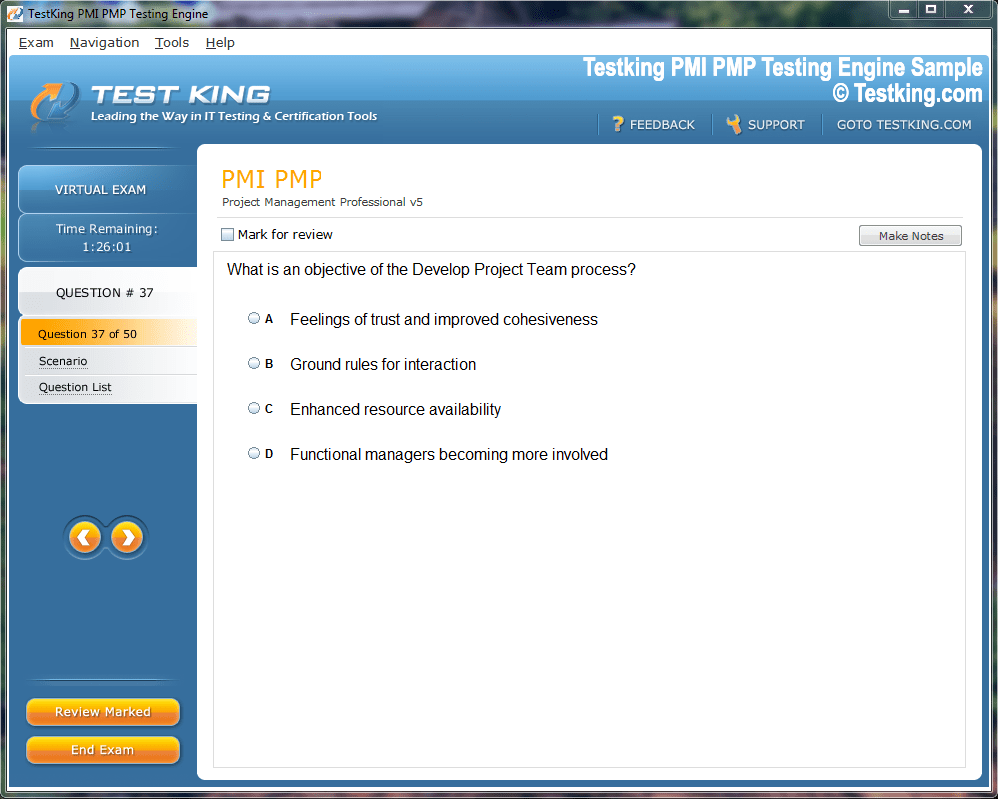

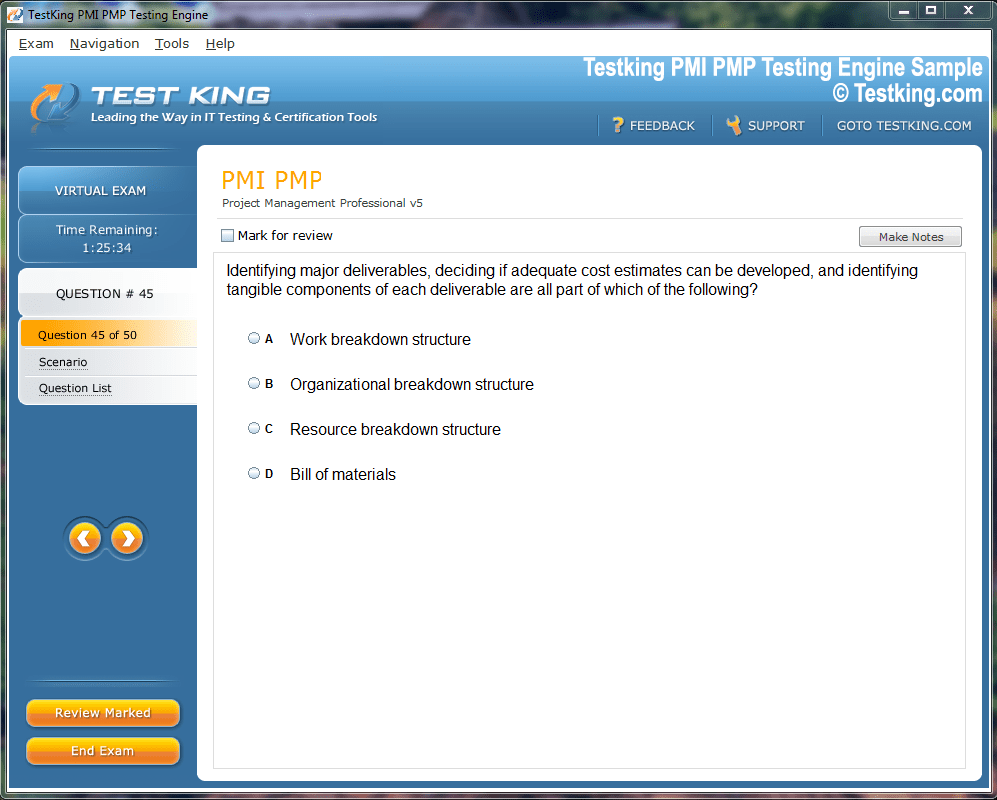

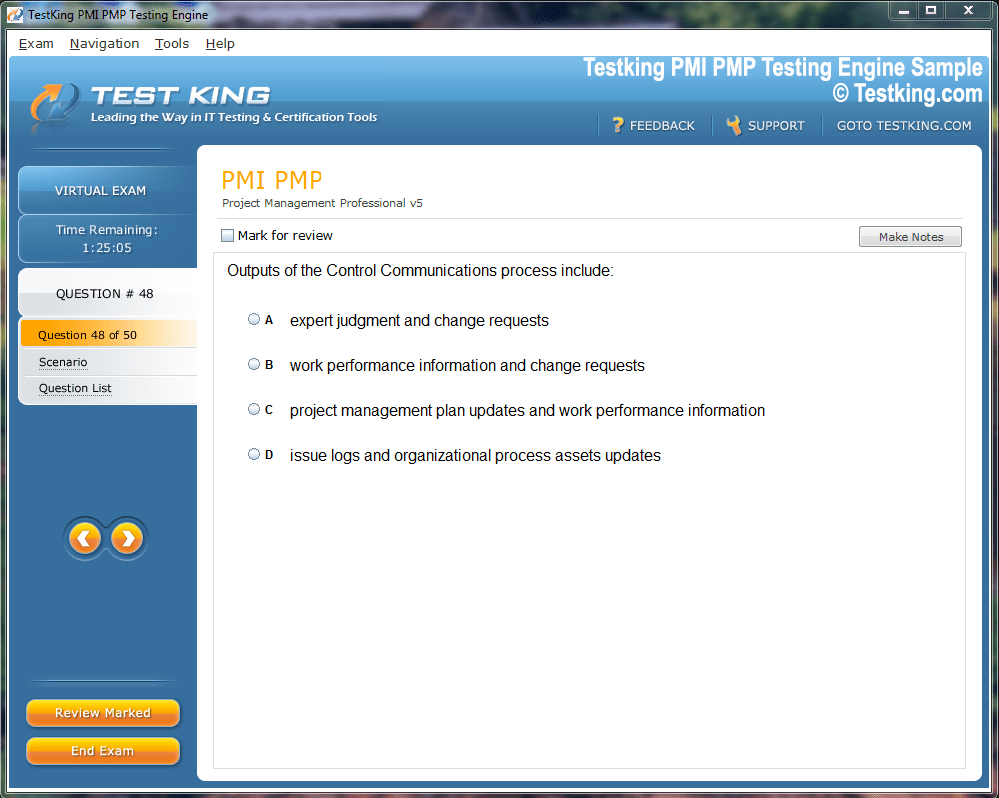

Product Screenshots

nop-1e =1

The Certified Fraud Examiner - Investigation Exam: A Foundational Guide

The Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) credential denotes proven expertise in fraud prevention, detection, and deterrence. CFEs are trained to identify the warning signs and red flags that indicate evidence of fraud and fraud risk. They are knowledgeable in the complex financial transactions often used in fraud schemes, the legal frameworks surrounding fraud investigations, and the methods used to uncover illicit activities. The CFE credential is awarded by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), the world's largest anti-fraud organization. Achieving this certification requires passing a rigorous CFE Exam, which tests a candidate's comprehensive understanding across four critical areas of fraud examination.

The CFE Exam is designed to be a comprehensive test of the skills and knowledge required in the anti-fraud profession. It is not merely an academic exercise; it is a professional benchmark that signifies a high level of competence. The exam is divided into four main sections: Financial Transactions & Fraud Schemes, Law, Investigation, and Fraud Prevention & Deterrence. Each section covers a unique body of knowledge, ensuring that a certified individual is a well-rounded expert. Preparing for the CFE Exam involves a deep dive into accounting principles, legal statutes, investigative techniques, and criminological theories, all of which form the foundation of a successful career in fraud examination.

The value of the CFE credential in the modern business and legal environment cannot be overstated. Organizations of all sizes, from multinational corporations to small non-profits, are susceptible to fraud. The financial and reputational damage caused by fraud can be devastating. Consequently, the demand for professionals who can effectively manage fraud risk is consistently high. CFEs are found in various roles, including internal and external auditing, forensic accounting, risk and compliance management, law enforcement, and consulting. The credential serves as a clear indicator to employers that an individual possesses the specialized skills necessary to protect an organization's assets and integrity.

The Pillars of Fraud: Understanding the Fraud Triangle

At the heart of fraud examination theory is the concept of the Fraud Triangle, a model developed by criminologist Donald R. Cressey. This framework is essential for understanding the conditions under which an ordinary person might commit fraud. It posits that three elements are typically present for occupational fraud to occur: a perceived non-shareable financial pressure, a perceived opportunity, and a way to rationalize the dishonest act. The CFE Exam requires candidates to have a deep understanding of this model because it provides a practical lens through which to analyze and investigate fraudulent behavior, moving beyond simple numbers to understand the human element involved.

The first side of the triangle is Pressure. This refers to the motivation or incentive behind the fraudulent act. The pressure is often financial and is considered "non-shareable" by the perpetrator, meaning they feel they cannot solve their problem through legitimate means or by confiding in others. Examples include overwhelming debt from gambling or medical bills, a desire to live beyond one's means, or intense pressure to meet unrealistic business performance targets. For a fraud examiner, identifying potential pressures on individuals in positions of trust is a critical step in assessing fraud risk and conducting an effective investigation.

The second element is Opportunity. This is the means by which an individual can commit fraud. Opportunity often arises from weak or nonexistent internal controls within an organization. For example, a single employee might have control over both recording and processing payments, with no independent oversight. This lack of segregation of duties creates a perfect opening for fraudulent activity. Other opportunities can stem from a lack of management review, poor security over assets, or an organizational culture that is overly trusting or indifferent to ethical conduct. A key part of the CFE Exam tests the ability to identify these control weaknesses that create such opportunities.

The final component of the Fraud Triangle is Rationalization. This is the internal justification that the perpetrator uses to make their dishonest actions seem acceptable to themselves. They must be able to reconcile their behavior with their own moral compass. Common rationalizations include "I was only borrowing the money," "The company owes it to me," "It's for a good purpose," or "They won't even miss it." Understanding these psychological mechanisms is crucial for investigators, especially during interviews, as it can help in structuring questions and interpreting the subject's responses, potentially leading to a confession.

Financial Transactions and Common Fraud Schemes

A significant portion of the CFE Exam is dedicated to Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes. This area requires a solid understanding of basic accounting and auditing concepts, as these are the tools used to both perpetrate and detect fraud. Candidates must be proficient in reading and analyzing financial statements, including the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. They need to understand how transactions are recorded and what constitutes a normal flow of business activity. This knowledge forms the baseline from which anomalies and red flags can be identified, signaling potential fraudulent manipulation of financial records.

The ACFE categorizes occupational fraud into three primary types: asset misappropriation, corruption, and financial statement fraud. Asset misappropriation is the most common type of fraud but typically causes the smallest median loss. It involves an employee stealing or misusing the organization's resources. This can include schemes like skimming revenues, stealing inventory, or creating fraudulent expense reimbursements. For the CFE Exam, candidates must be familiar with the various sub-schemes within this category, such as check tampering, payroll fraud, and billing schemes, and understand the internal control weaknesses that allow them to occur.

Corruption schemes involve an employee using their influence in business transactions in a way that violates their duty to the employer for their own direct or indirect benefit. These schemes can be harder to detect than simple theft because they often involve collusion between an employee and an outside party. Examples include bribery, conflicts of interest, illegal gratuities, and economic extortion. A CFE must understand how to look for red flags such as unusually close relationships with vendors, lavish lifestyles that don't match an employee's salary, or a pattern of awarding contracts without competitive bidding.

Financial statement fraud is the least common type of occupational fraud but is by far the most costly in terms of median loss. These schemes involve the intentional misstatement or omission of material information in the organization's financial reports. The goal is typically to deceive investors, creditors, and other users of the financial statements about the company's true financial performance or condition. Common methods include recording fictitious revenues, concealing liabilities, and improperly valuing assets. The CFE Exam tests a candidate's ability to use analytical techniques, such as vertical and horizontal analysis, to spot the signs of such manipulation.

The Legal Framework of a Fraud Examination

Fraud examination does not occur in a vacuum; it is deeply intertwined with the legal system. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the legal elements of fraud is a cornerstone of the CFE Exam and the profession itself. Fraud examiners must operate within the bounds of the law to ensure that any evidence collected is admissible in court and that the rights of all parties are respected. The "Law" section of the CFE Exam covers the many facets of the legal system that are relevant to fraud cases, including criminal and civil law, rules of evidence, and the legal process from investigation to trial.

Candidates must be able to distinguish between criminal law and civil law as they apply to fraud. A criminal case is brought by the government and seeks to punish the wrongdoer with fines or imprisonment. The burden of proof is "beyond a reasonable doubt." In contrast, a civil case is brought by an individual or entity to recover damages or losses, and the burden of proof is typically a "preponderance of the evidence," which is a lower standard. A CFE needs to know how the objectives and procedures of an investigation might differ depending on whether the ultimate goal is criminal prosecution or civil litigation.

The rules of evidence are another critical area of study for the CFE Exam. Fraud examiners are responsible for gathering documents, data, and testimony that can be used to prove or disprove a fraud allegation. They must understand concepts like relevance, authenticity, and the chain of custody to ensure that the evidence they collect will be accepted by the court. They also need to be aware of rules against hearsay and the various exceptions, as well as legal privileges that can protect certain communications, such as those between an attorney and a client. Mishandling evidence can jeopardize an entire case.

Finally, the CFE Exam tests knowledge of the specific statutes that make fraudulent acts illegal. This includes laws related to mail fraud, wire fraud, bank fraud, securities fraud, and money laundering, among others. A CFE is not expected to be a lawyer but must have sufficient legal knowledge to recognize potential violations, gather the appropriate evidence to support a legal case, and communicate effectively with legal counsel. This legal acumen ensures that the work of the fraud examiner serves its ultimate purpose: holding perpetrators accountable and providing a remedy for the victims of fraud.

Planning and Conducting a Fraud Examination

A successful fraud examination does not begin with random acts of investigation; it starts with a meticulous plan. The planning phase is a critical component tested on the CFE Exam and is essential in practice to ensure the investigation is efficient, effective, and legally sound. The process typically begins with a predicate, which is the totality of circumstances that would lead a reasonable, professionally trained, and prudent individual to believe a fraud has occurred, is occurring, or will occur. Once a predicate exists, the examiner can begin to formulate a plan. This involves defining the objectives of the investigation, such as proving or disproving the allegation, identifying the perpetrators, and quantifying the loss.

The investigative plan should be a dynamic document, adaptable to new information as it is uncovered. It outlines the specific procedures to be performed, the evidence to be gathered, and the resources required. A key early step is to form a hypothesis based on the initial information. For example, if there is a suspicion of a billing scheme, the hypothesis might be that an employee has created a shell company and is submitting false invoices. The investigation would then be designed to test this hypothesis by gathering evidence related to vendor files, invoices, and payments. This hypothesis-driven approach ensures the investigation remains focused and avoids becoming a "fishing expedition."

Conducting the examination involves executing the steps outlined in the plan. This often proceeds from the general to the specific. Investigators may start by analyzing broad sets of data, such as the entire vendor master file, before narrowing their focus to specific high-risk transactions or individuals. The sequence of investigation is also crucial. It is often best to start with non-confrontational methods, such as reviewing public records and internal documents, before moving on to more direct methods like surveillance or interviews. This strategy allows the examiner to build a solid foundation of evidence before alerting potential subjects to the investigation.

Throughout the process, maintaining confidentiality is paramount. A premature leak of information can compromise the investigation, allow perpetrators to destroy evidence, or unfairly damage the reputations of innocent individuals. The fraud examiner must act with discretion and professionalism, ensuring that information is shared only on a need-to-know basis. Proper planning and a methodical approach to conducting the examination not only increase the likelihood of a successful outcome but also demonstrate the professionalism and competence expected of a Certified Fraud Examiner, a key focus of the CFE Exam curriculum.

The Art of the Interview

Interviewing is one of the most critical skills for a fraud examiner and a major topic within the CFE Exam's investigation section. An interview is a structured conversation with a purpose, designed to elicit information from witnesses, victims, and even potential subjects. The ability to conduct effective interviews can often mean the difference between a successful and an unsuccessful investigation. A CFE must understand the psychology of interviewing, how to build rapport, how to structure questions, and how to interpret both verbal and non-verbal responses. The goal is to gather facts and evidence in a fair and objective manner.

There are different types of interviews for different stages of an investigation. Informational interviews are conducted with witnesses who are not suspected of wrongdoing but may have information relevant to the case. The goal here is to gather background information and corroborate facts. A more sensitive type of interview is the admission-seeking interview, which is reserved for the primary suspect and is conducted only after a substantial amount of evidence has been gathered. The objective of this interview is to obtain a confession or an admission of guilt. This requires careful planning and a deep understanding of interrogation techniques.

Effective questioning is the core of any interview. Examiners should primarily use open-ended questions (e.g., "Tell me about the payment approval process") to encourage the witness to provide a detailed narrative. Closed-ended questions (e.g., "Did you approve this invoice?") can be used to confirm specific details, while leading questions should generally be avoided as they can taint the witness's response. The interviewer must also be an active listener, paying close attention to what is said and how it is said. Inconsistencies, evasiveness, or changes in demeanor can be important indicators that require further probing.

Interpreting verbal and non-verbal cues is another essential skill. While not foolproof, changes in body language, tone of voice, and eye contact can provide clues about a person's truthfulness or emotional state. For example, a person who is being deceptive may exhibit signs of stress, such as fidgeting, avoiding eye contact, or providing overly defensive answers. A trained fraud examiner uses these observations not as definitive proof of lying, but as signals to explore certain topics more deeply. Mastering the art of the interview is a hallmark of an experienced CFE and a key to successfully resolving fraud cases.

Evidence: Collection, Handling, and Management

The entire fraud examination process revolves around evidence. It is the evidence that proves or disproves the fraud allegation, identifies the guilty parties, and supports legal action. The CFE Exam places significant emphasis on the proper collection, handling, and management of evidence because any mistake in this process can render the evidence useless. Evidence in a fraud case can take many forms, including documentary evidence (e.g., invoices, contracts, emails), physical evidence (e.g., stolen assets), and testimonial evidence (e.g., statements from witnesses). A CFE must be able to identify, gather, and preserve all relevant forms of evidence.

One of the most critical concepts in evidence management is the chain of custody. This is a chronological record that documents the possession, handling, and location of a piece of evidence from the moment it is collected until it is presented in court. A clear and unbroken chain of custody is required to prove that the evidence has not been altered, tampered with, or substituted. Each person who handles the evidence must sign for it, and every transfer must be documented. Failure to maintain a proper chain of custody is a common reason for evidence to be deemed inadmissible in a legal proceeding.

The collection of evidence must be done systematically and ethically. For documentary evidence, it is often best to obtain original documents whenever possible. If only copies are available, they should be authenticated. Examiners should create a detailed inventory of all evidence collected, noting what was taken, from where, when, and by whom. For digital evidence, such as data from a computer, specialized forensic techniques are required to create a perfect "image" of the hard drive without altering the original data in any way. This process ensures the digital evidence remains pristine and can withstand legal scrutiny.

Proper management of evidence throughout the investigation is just as important as its initial collection. Evidence should be stored in a secure location with restricted access to prevent loss or unauthorized viewing. The examiner must organize the vast amounts of information and documents collected in a logical manner, often using case management software. This organization is vital for building a coherent narrative of the fraud scheme and for preparing a final report that clearly presents the findings. The CFE Exam ensures that certified professionals understand these meticulous procedures, which are fundamental to the integrity and success of any investigation.

Leveraging Data Analytics and Forensic Testing

In today's digital world, nearly all financial transactions leave an electronic footprint. This has made data analytics and forensic testing indispensable tools for the modern fraud examiner. The CFE Exam reflects this reality by testing a candidate's understanding of how technology can be used to detect and investigate fraud. Data analytics involves examining large sets of data to identify outliers, patterns, anomalies, and red flags that may indicate fraudulent activity. Instead of manually reviewing thousands of transactions, an examiner can use specialized software to quickly pinpoint areas of high risk, making the investigation far more efficient and effective.

A variety of data analysis techniques can be applied in a fraud investigation. For example, an examiner might use data mining to search for duplicate payments to a vendor, payments made on weekends or holidays, or invoices that fall just below a required approval threshold. Benford's Law, a statistical principle, can be used to analyze the frequency of digits in a set of numbers to identify fabricated data. Other tests can identify phantom employees on a payroll register or uncover conflicts of interest by matching employee addresses with vendor addresses. These tests can provide powerful, objective evidence of a fraudulent scheme.

Digital forensics is a specialized branch of forensic science that deals with the recovery and investigation of material found in digital devices. When a fraud scheme involves computers, smartphones, or other electronic devices, a digital forensics expert may be needed. These experts can recover deleted files, analyze email history, and trace a user's internet activity. This can provide crucial evidence, such as a fraudulent spreadsheet saved on a suspect's computer or emails showing collusion between an employee and a vendor. The CFE needs to understand when to call in such specialists and how to work with them to properly collect and analyze digital evidence.

The use of these technological tools does not replace traditional investigative techniques but rather enhances them. The results of data analysis can help an examiner focus their efforts, identify key documents for review, and formulate more effective questions for interviews. For example, if data analysis reveals a series of suspicious payments to a particular vendor, the examiner knows to pull the corresponding invoices and interview the employee who approved them. A solid understanding of how to integrate data analytics and forensic testing into an investigation is a critical skill for any CFE and a key subject area for the certification exam.

Deconstructing Financial Statements for Fraud

Financial statement analysis is a core competency for any Certified Fraud Examiner and a fundamental topic on the CFE Exam. While auditors look at financial statements to ensure they are presented fairly, fraud examiners scrutinize them with a different goal: to find evidence of intentional deception. This requires a forensic mindset, looking beyond the surface numbers to identify inconsistencies and red flags that could indicate a fraudulent scheme. The examiner must be proficient in analyzing the three main financial statements: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the statement of cash flows. Each statement tells a different part of the company's story and can hold clues to potential manipulation.

Several analytical techniques are employed to detect anomalies. Vertical analysis, for instance, involves restating each line item on a financial statement as a percentage of a base figure, such as total assets on the balance sheet or total sales on the income statement. This allows for the comparison of a company's financial makeup over time or against industry benchmarks. A sudden, unexplained change in a percentage can be a red flag. Horizontal analysis, on the other hand, compares line items across multiple periods to identify unusual trends. For example, if revenues are increasing by 20% year-over-year while accounts receivable are increasing by 80%, it could suggest the company is recording fictitious sales.

Beyond these basic techniques, ratio analysis is a powerful tool. By calculating and tracking financial ratios—such as the current ratio, debt-to-equity ratio, or inventory turnover—an examiner can spot trends that deviate from historical norms or industry standards. For example, a declining inventory turnover ratio might indicate that obsolete inventory is being carried on the books at an inflated value, a common way to overstate assets. The CFE Exam expects candidates to be comfortable with these analytical methods and to understand what different anomalies might signify in the context of a potential fraud scheme.

Ultimately, the goal of financial statement analysis in a fraud context is to identify areas that require further investigation. It rarely provides definitive proof of fraud on its own, but it is an essential starting point that helps the examiner focus their efforts. It allows them to develop a more specific hypothesis about the nature of the potential fraud and guides them toward the specific documents, transactions, and individuals that need to be examined more closely. This analytical skill is what separates a fraud examiner from a traditional accountant and is a critical part of the CFE body of knowledge.

Unraveling Asset Misappropriation Schemes

Asset misappropriation is by far the most common category of occupational fraud, although it often results in lower median losses compared to financial statement fraud. This section of the CFE Exam covers the many ways employees can steal or misuse an organization's resources. These schemes can be broadly divided into two types: cash schemes and non-cash schemes. A thorough understanding of how these schemes work is essential for both detection and prevention. Examiners must know the specific red flags and control weaknesses associated with each type of scheme to effectively investigate and recommend corrective actions.

Cash misappropriation schemes are numerous and varied. They include skimming, which is the theft of cash before it is recorded in the accounting system, and cash larceny, which is the theft of cash after it has been recorded. For example, an employee might pocket cash from a sale and never ring it up on the register. Another major subcategory is fraudulent disbursements, where the perpetrator causes the organization to make a payment for a fictitious purpose. This includes billing schemes (creating a shell company to submit fake invoices), check tampering (altering or forging company checks), and expense reimbursement schemes (submitting false claims for business expenses).

Non-cash misappropriation involves the theft or misuse of physical assets such as inventory and equipment. An employee in a warehouse might steal inventory and sell it, or a manager might use company equipment for a personal side business. These schemes can be more difficult to conceal than cash theft because the missing assets create a discrepancy between the physical count and the perpetual inventory records. Perpetrators may try to hide the theft by falsifying records, such as writing off the stolen items as damaged or obsolete.

Detecting asset misappropriation requires a combination of strong internal controls, vigilant management oversight, and specific audit tests. For example, to detect a billing scheme, an examiner might analyze the vendor master file for suspicious details like vendors with no physical address or phone number, or they might match vendor addresses against employee addresses. For inventory theft, regular physical counts and reconciliations are crucial. The CFE Exam requires candidates to not only understand the mechanics of these schemes but also the specific control activities that are most effective in preventing and detecting them.

Exposing Corruption and Bribery

Corruption schemes represent a significant threat to organizations, as they can undermine business integrity, lead to substantial financial loss, and cause severe reputational damage. This area of the CFE Exam focuses on schemes where an employee uses their position of influence to gain an improper personal benefit. Unlike asset misappropriation, corruption cases almost always involve a third party colluding with the employee. These schemes are often difficult to detect because they can be concealed within what appear to be legitimate business transactions. The four main types of corruption are conflicts of interest, bribery, illegal gratuities, and economic extortion.

A conflict of interest occurs when an employee has an undisclosed personal or economic interest in a transaction that could adversely affect the organization. For example, a purchasing manager might award a contract to a company that is secretly owned by a family member, even if that company does not offer the best price or quality. The organization is harmed because it is not getting the benefit of a fair and competitive bidding process. Detecting these schemes often involves comparing vendor and employee records and looking for undisclosed relationships.

Bribery involves offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting anything of value to influence an official act or a business decision. For instance, a vendor might pay a kickback to a manager in exchange for the manager approving the vendor's inflated invoices. The kickback is the bribe, and the approval of the invoices is the influenced business decision. Illegal gratuities are similar, but they are given as a reward for a decision after the fact, rather than as an inducement before the decision is made. Bribery schemes are notoriously hard to uncover and often require a tip from a whistleblower or proactive data analysis to identify suspicious payment patterns.

Economic extortion is the opposite of bribery. In this case, an employee demands a payment from a vendor or third party in order to make a particular business decision. For example, an inspector might demand a payment from a contractor to approve their substandard work. The employee is essentially holding the vendor's business hostage. To prepare for the CFE Exam, candidates must understand the legal definitions and mechanics of each of these corruption schemes, as well as the behavioral red flags and internal control weaknesses that are commonly associated with them.

The Fraud Examiner in the Courtroom

The culmination of a fraud examiner's work is often their participation in legal proceedings. This can involve providing documents, assisting legal counsel in preparing for trial, and, most importantly, testifying as a witness. The CFE Exam tests the candidate's understanding of the examiner's role in the courtroom, particularly as an expert witness. An expert witness is someone who, by virtue of their knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, has specialized knowledge in a particular field that is beyond that of the average person. This expertise allows them to offer opinions on matters within their field, which a lay witness is not permitted to do.

Preparing to testify is an exhaustive process. The CFE must prepare a detailed report outlining their findings, the evidence they relied upon, and the conclusions they reached. This report will be scrutinized by the opposing counsel. The examiner must be prepared to defend every aspect of their investigation and analysis. Before trial, they may be required to give a deposition, which is sworn testimony given out of court that can be used during the trial. The CFE must be thoroughly familiar with all the facts of the case and be able to present them clearly and concisely.

During the trial, the expert witness will be questioned by both the attorney who hired them (direct examination) and the opposing attorney (cross-examination). On direct examination, the goal is to present the findings of the investigation to the jury in a way that is easy to understand. The CFE should avoid jargon and speak clearly and professionally. On cross-examination, the opposing counsel will try to challenge the expert's credibility, qualifications, and conclusions. The CFE must remain calm, professional, and objective, answering questions truthfully and without becoming defensive.

The credibility of the expert witness is paramount. Their demeanor, professionalism, and perceived objectivity can have a significant impact on how the jury views their testimony. The CFE's ultimate duty is to the court and to the truth, not to the party that hired them. They must present their findings fairly and honestly, regardless of whether those findings help or hurt their client's case. Understanding the pressures and responsibilities of testifying is a key skill for any fraud examiner and an important part of the knowledge base required for the CFE certification.

Corporate Culture and the Tone at the Top

An organization's culture is one of the most powerful forces in either promoting ethical behavior or allowing fraud to fester. The CFE Exam emphasizes the importance of corporate culture as a primary fraud prevention control. A culture of integrity, transparency, and accountability can create an environment where fraud is less likely to occur and more likely to be detected if it does. This culture is not created by a mission statement on a wall; it is built through the consistent actions and communications of the organization's leadership.

The concept of "tone at the top" is central to this discussion. This refers to the ethical atmosphere that is created in the workplace by the organization's leadership. When senior executives and the board of directors demonstrate a clear commitment to ethical conduct and a zero-tolerance policy towards fraud, that message cascades down through the entire organization. Employees take their cues from their leaders. If they see that management cuts corners or acts unethically, they are more likely to believe that such behavior is acceptable for them as well. A strong tone at the top is the foundation of an effective anti-fraud program.

This ethical culture must be supported by concrete policies and procedures. This includes having a clear and comprehensive code of conduct that is regularly communicated to all employees. It also involves creating a positive work environment where employees feel valued and respected. Research has shown that disgruntled or mistreated employees are more likely to rationalize fraudulent acts as a way of getting back at the company. Promoting organizational justice and treating employees fairly can significantly reduce this risk.

A key component of a strong anti-fraud culture is a robust whistleblower program. Employees are often the first to know about fraudulent activity, but they may be hesitant to come forward for fear of retaliation. A well-designed program provides a safe and confidential channel for employees to report their concerns without fear. It demonstrates that the organization is serious about uncovering wrongdoing and protects those who have the courage to speak up. The CFE Exam tests a candidate's understanding of how these cultural and governance elements work together to create a powerful defense against fraud.

The ACFE Code of Professional Ethics: A Practical Guide

The Certified Fraud Examiner credential is a mark of high professional and ethical standards. Adherence to a strict ethical code is not just a recommendation; it is a requirement for all CFEs. The ACFE Code of Professional Ethics serves as the guiding principle for the conduct of all members. The CFE Exam ensures that candidates have a thorough understanding of this code and are prepared to apply it in real-world situations. The code is built on a foundation of integrity, objectivity, and professional competence, and it is the bedrock of the public's trust in the CFE designation.

The code mandates that a CFE shall demonstrate a commitment to professionalism. This includes acting with integrity and diligence in the performance of their duties and refraining from any conduct that would bring discredit to the profession. It means being honest and straightforward in all professional relationships and never being a party to any illegal or improper activity. Objectivity is another cornerstone. A CFE must remain impartial and free from conflicts of interest in all engagements. Their conclusions must be based on the evidence, not on any personal bias or pressure from a client.

Confidentiality is a critical ethical obligation. During an investigation, a CFE will often be privy to sensitive and confidential information. The code strictly prohibits the disclosure of this information without proper legal or professional authorization. This duty of confidentiality extends even after an engagement has concluded. A breach of confidentiality can not only damage the reputation of the CFE but can also jeopardize the investigation and cause significant harm to the individuals and organizations involved.

Finally, the code requires CFEs to maintain their professional competence. The field of fraud examination is constantly evolving, with new schemes and new technologies emerging all the time. A CFE has an obligation to continually improve their skills and knowledge through ongoing education and training. They must not accept engagements for which they are not qualified. This commitment to lifelong learning ensures that CFEs remain at the forefront of the anti-fraud profession and can provide the highest level of service to their clients and employers.

Mastering the CFE Exam: A Strategy for Success

Passing the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam is a challenging but achievable goal that requires a well-thought-out study plan and a disciplined approach. The exam covers a vast body of knowledge, and simply reading the material is not enough. Candidates need a strategy to absorb, retain, and apply the information effectively. The first step is to become familiar with the exam's structure and content. The exam is divided into four sections: Financial Transactions & Fraud Schemes, Law, Investigation, and Fraud Prevention & Deterrence. Understanding the key topics covered in each section allows you to assess your own strengths and weaknesses and allocate your study time accordingly.

The primary study resource recommended by the ACFE is the CFE Exam Prep Course. This comprehensive tool is specifically designed to align with the exam content. It includes detailed study guides, practice questions, and simulated exams that mimic the format and difficulty of the real test. A key strategy for success is to work through the Prep Course methodically. Don't just passively read the material; actively engage with it. Take notes, create flashcards for key concepts, and consistently test your knowledge with the practice questions.

Time management is crucial, both during your study period and on exam day. Create a realistic study schedule that you can stick to over several weeks or months. Trying to cram all the information in a short period is a recipe for failure. During the exam itself, be mindful of the clock. Each section has a time limit, so it's important to pace yourself. If you encounter a difficult question, make your best guess, flag it for review if time permits, and move on. Don't let one challenging question derail your progress on the rest of the section.

Finally, practice is the key to confidence. The more practice questions and simulated exams you complete, the more comfortable you will become with the types of questions asked and the level of detail required. Review your answers, paying close attention to the questions you got wrong. Understand why the correct answer is right and why your answer was wrong. This process of active learning and self-assessment is the most effective way to prepare for the CFE Exam and to ensure you are ready to demonstrate your mastery of the fraud examination discipline on test day.

Conclusion

The path to becoming a Certified Fraud Examiner, culminating in the successful completion of the CFE Exam, is a journey that transcends mere technical knowledge. It is an immersion into a multidisciplinary field that requires a unique blend of psychological insight, ethical fortitude, and strategic preparation. The final, yet perhaps most crucial, pieces of this puzzle involve understanding the mindset of the fraudster, the cultural environment that can either enable or prevent their actions, and the unwavering ethical code that must guide the examiner's every move. To truly combat fraud, one must look beyond the balance sheets and legal statutes to comprehend the human factors at play. The study of criminology provides this essential context, offering frameworks like the Fraud Diamond to explain not just how fraud happens, but why. Recognizing the behavioral red flags—the sudden lifestyle changes, the defensiveness, the refusal to take a vacation—allows an examiner to add a layer of human observation to their analytical skills, often leading them to perpetrators who might otherwise go unnoticed.

This understanding of individual psychology is magnified when considering the corporate environment. An organization's culture, dictated by the "tone at the top," is the single most powerful fraud prevention tool at its disposal. A leadership team that consistently demonstrates a commitment to integrity creates a ripple effect throughout the company, fostering an atmosphere where unethical behavior is unacceptable. Conversely, a culture of lax oversight, where leaders themselves cut corners, provides the fertile ground in which fraud can take root and grow. A CFE must be more than just an investigator; they must also be a trusted advisor who can help an organization build these cultural defenses, promoting transparency, accountability, and a safe environment for whistleblowers. This proactive, preventative role is as vital as any reactive investigation.

Underpinning all of this is the ACFE Code of Professional Ethics. This is not a set of optional guidelines; it is the absolute, non-negotiable foundation of the profession. The CFE credential has value because the public and employers trust that the person holding it will act with unwavering integrity, objectivity, and competence. This code governs every aspect of an examiner's work, from maintaining the confidentiality of sensitive information to remaining impartial in the face of pressure. It is this ethical commitment that ensures a CFE's findings are credible and that their ultimate loyalty is to the truth. Violating this code does not just risk an individual's career; it damages the reputation of the entire profession.

Finally, the journey comes down to the CFE Exam itself. Success is not a matter of chance but of deliberate and strategic preparation. It requires a disciplined approach, leveraging dedicated resources like the CFE Exam Prep Course to master the vast and diverse body of knowledge. It demands effective time management, a commitment to consistent practice, and the resilience to learn from mistakes. Passing the exam is the final validation, the formal recognition that a candidate has acquired the necessary skills and knowledge to join the ranks of a global community of anti-fraud experts. It is a challenging endeavor, but one that opens the door to a rewarding career dedicated to the pursuit of truth and justice in the business world.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I download my products after I have completed the purchase?

Your products are available immediately after you have made the payment. You can download them from your Member's Area. Right after your purchase has been confirmed, the website will transfer you to Member's Area. All you will have to do is login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long will my product be valid?

All Testking products are valid for 90 days from the date of purchase. These 90 days also cover updates that may come in during this time. This includes new questions, updates and changes by our editing team and more. These updates will be automatically downloaded to computer to make sure that you get the most updated version of your exam preparation materials.

How can I renew my products after the expiry date? Or do I need to purchase it again?

When your product expires after the 90 days, you don't need to purchase it again. Instead, you should head to your Member's Area, where there is an option of renewing your products with a 30% discount.

Please keep in mind that you need to renew your product to continue using it after the expiry date.

How often do you update the questions?

Testking strives to provide you with the latest questions in every exam pool. Therefore, updates in our exams/questions will depend on the changes provided by original vendors. We update our products as soon as we know of the change introduced, and have it confirmed by our team of experts.

How many computers I can download Testking software on?

You can download your Testking products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers/devices. To use the software on more than 2 machines, you need to purchase an additional subscription which can be easily done on the website. Please email support@testking.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our testing engine is supported by all modern Windows editions, Android and iPhone/iPad versions. Mac and IOS versions of the software are now being developed. Please stay tuned for updates if you're interested in Mac and IOS versions of Testking software.