Test Name: SBAC - Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium

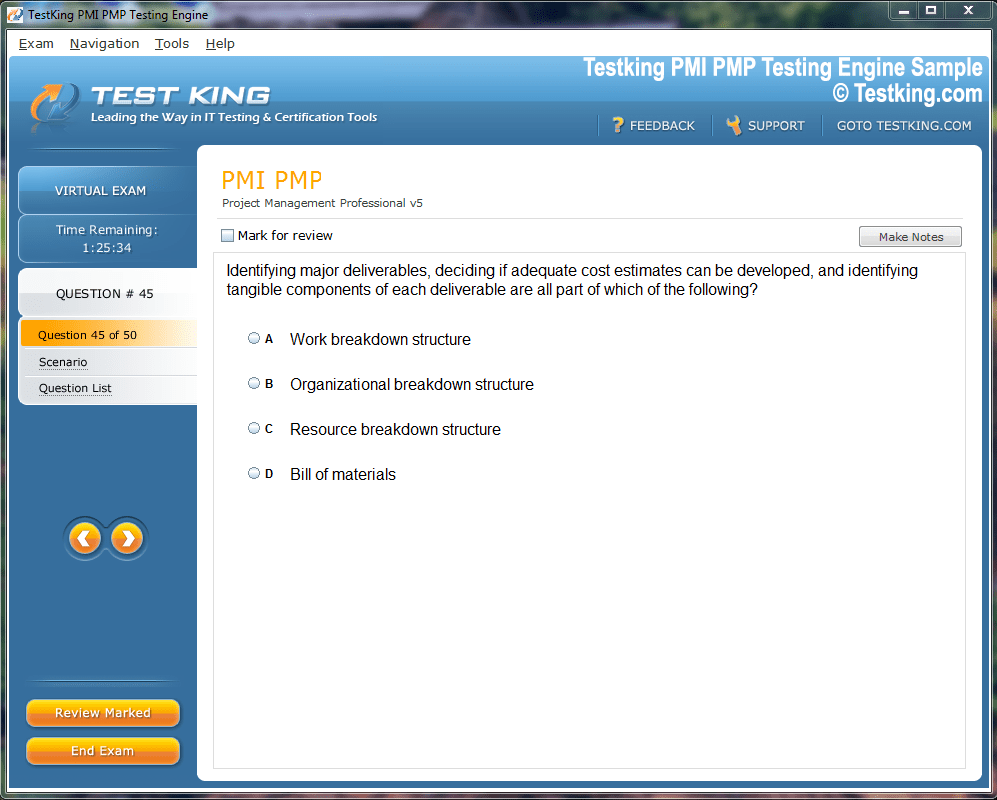

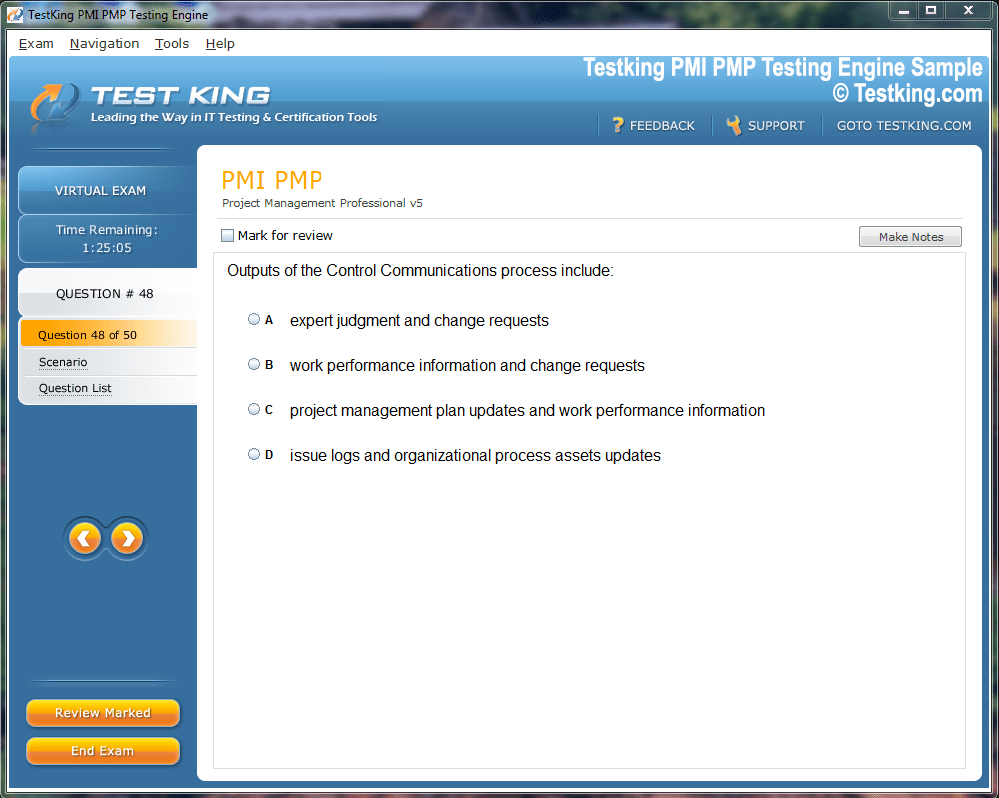

Product Screenshots

nop-1e =1

SBAC Certification and the Transformation of Classroom Learning

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, often abbreviated as SBAC, is an educational framework created to measure student progress and learning consistency across states that have adopted the Common Core State Standards. The goal of this initiative is not merely to test students, but to gauge how effectively the curriculum aligns with learning outcomes that emphasize analytical thinking, comprehension, and applied knowledge. Unlike earlier standardized tests that primarily measured memorization, the SBAC aims to capture a student’s ability to reason, evaluate, and synthesize information in a modern academic setting.

This assessment system emerged from a collective demand for a more equitable and adaptive form of testing that transcends traditional boundaries of paper-based exams. With the rise of digital learning environments and online educational resources, the SBAC introduced a computer-adaptive testing model that adjusts in real time based on the student’s responses. The intent behind this innovation is to ensure that each student experiences a test tailored to their ability level, providing a more accurate reflection of what they know and how they think.

However, as with many large-scale educational reforms, the implementation of the SBAC has not been without complications. Early testing phases revealed a range of technical and logistical difficulties that schools had to navigate. For instance, some districts faced connectivity issues, malfunctioning testing interfaces, and disparities in technology access between schools. These challenges illuminated an ongoing concern within the educational ecosystem—ensuring that every student, regardless of their school’s resources, receives a fair and consistent assessment experience.

The philosophical foundation of the SBAC lies in the idea that education should measure not only what a student recalls but how they apply that knowledge to unfamiliar scenarios. Traditional testing methods often fail to capture higher-order thinking skills, leaving educators with an incomplete picture of student development. The SBAC attempts to fill that void by introducing a format that interlaces reading comprehension, problem-solving, and conceptual reasoning.

The consortium that designed this system involves educators, administrators, researchers, and assessment specialists from multiple states. Their collaboration aims to create a unified standard that can adapt to the diverse learning environments of American schools while maintaining a rigorous and transparent evaluation framework. In practice, this means that students from different regions encounter tests that are consistent in difficulty and content scope, making it possible to analyze data across state lines in a meaningful way.

As schools transitioned toward using the SBAC, educators began to notice its similarities to other well-known standardized assessments, such as the SAT, albeit in a less complex format suitable for K–12 education. Students encounter a mixture of multiple-choice questions, short responses, and analytical writing tasks. What distinguishes the SBAC from previous assessments is the way it layers interconnected questions. For example, a student might answer part A of a question incorrectly and, as a result, be guided into a corresponding part B that builds on the initial response. This structure not only tests accuracy but also reveals how students reason through their mistakes or misinterpretations.

Beyond structure and content, the SBAC seeks to redefine how schools interpret student performance data. Rather than offering a simple pass or fail outcome, the test provides detailed feedback on individual strengths and weaknesses across several domains. This diagnostic approach is intended to help educators fine-tune their teaching strategies and offer more targeted support to students who struggle in specific areas. It also empowers administrators to make informed decisions about curriculum development and resource allocation based on empirical data rather than assumptions.

The introduction of a computer-adaptive testing model represents one of the most significant shifts in modern assessment philosophy. This adaptive method means that the test dynamically adjusts its level of difficulty depending on each student’s previous responses. A correct answer prompts a slightly harder question, while an incorrect one triggers a less challenging follow-up. This continuous adjustment generates a precise measure of ability, distinguishing between students who might otherwise appear to have similar proficiency levels on a traditional static exam.

However, while this adaptive approach is intellectually compelling, it also presents several obstacles. For one, digital testing presupposes a certain level of technological literacy. Younger students or those with limited access to computers at home may experience added anxiety and reduced performance, not because of a lack of academic ability, but due to unfamiliarity with digital tools. Furthermore, technical malfunctions—ranging from frozen screens to unresponsive components—can disrupt the flow of testing, leading to incomplete results or invalid data. These operational issues highlight the tension between innovation and practicality in modern education systems.

Another key feature of the SBAC is its focus on integrated learning. Rather than compartmentalizing knowledge into isolated subjects, the test often presents scenarios that require students to apply skills from multiple disciplines simultaneously. For instance, a reading comprehension passage might include data interpretation elements that demand mathematical reasoning, or a science-related prompt may require written analysis and argumentation. This cross-disciplinary approach reflects a growing recognition that real-world problem-solving rarely fits neatly within a single subject category.

The SBAC’s emphasis on critical thinking and interdisciplinary application aligns with the broader goals of the Common Core Standards. These standards were designed to ensure that students across the United States receive a consistent and challenging education that prepares them for college, careers, and civic engagement. The SBAC serves as a mechanism for evaluating how effectively these goals are being met.

Despite these intentions, the transition to SBAC testing has prompted widespread debate within the educational community. Some educators welcome the change as a necessary modernization of outdated testing systems. Others view it with skepticism, questioning whether standardized testing—no matter how sophisticated—can truly capture the nuances of student learning. Critics argue that the reliance on digital platforms can widen existing inequities, as wealthier districts with better technological infrastructure gain an inherent advantage.

In addition, concerns have been raised about test fatigue among students. As education systems continue to emphasize measurable outcomes, the frequency of assessments can lead to exhaustion and disengagement. The SBAC’s extended testing sessions, combined with their adaptive nature, demand sustained concentration that some students find difficult to maintain. For younger learners in particular, the cognitive load of navigating unfamiliar interfaces while also processing complex content can be overwhelming.

Educators, on the other hand, face their own challenges. While the SBAC provides detailed performance data, interpreting that information and translating it into actionable teaching strategies requires significant training and support. The analytics behind adaptive testing are complex, and many teachers have expressed the need for professional development to effectively use the insights generated by the assessments. Without sufficient guidance, valuable data may remain underutilized or misunderstood.

The development of the SBAC also reflects a philosophical evolution in how learning is conceptualized. Historically, education systems emphasized rote memorization and standardized content mastery. Modern educational theory, however, prioritizes flexibility, problem-solving, and transferable skills. The SBAC attempts to bridge these perspectives by combining factual knowledge assessment with scenarios that require reasoning and adaptability.

The consortium’s emphasis on uniformity across states introduces another layer of complexity. While a unified standard ensures consistency, it can also limit local flexibility. States and school districts vary in demographics, economic resources, and pedagogical approaches. Applying a single testing framework across such diverse contexts requires careful calibration to avoid marginalizing students whose learning experiences deviate from the dominant model.

An intriguing aspect of the SBAC’s design is its potential to evolve over time. Unlike static paper-based tests, digital platforms allow for continuous updates to question banks, scoring algorithms, and reporting formats. This adaptability enables the consortium to refine the system based on empirical evidence from each testing cycle. Over successive years, the SBAC can theoretically become more accurate and responsive, reflecting ongoing advancements in both pedagogy and technology.

Nevertheless, adaptability introduces its own challenges. Frequent modifications can create instability for educators who must regularly adjust their teaching strategies to align with updated assessment formats. Students, too, may experience confusion if question structures or scoring criteria shift between years. Balancing innovation with consistency remains one of the central dilemmas of digital assessment design.

Beyond its technical components, the SBAC represents a cultural shift in how society views education. It reflects a movement toward accountability, data-driven decision-making, and evidence-based policy. Yet this reliance on data also carries risks. Quantitative measurements can oversimplify the complex realities of learning, reducing students to numbers and percentile rankings. While data can reveal patterns, it cannot always capture creativity, resilience, or emotional intelligence—qualities equally vital for lifelong success.

The scoring methodology of the SBAC further differentiates it from older assessments. Instead of a single composite score, results are broken down into performance levels that correspond to varying degrees of proficiency. These levels help educators understand not just whether a student passed or failed, but where they stand on a continuum of development. The nuanced feedback aims to guide instruction, support remediation, and encourage growth rather than punishment.

Despite these benefits, transparency about how scores are calculated remains limited. Many educators have voiced uncertainty about which question types carry more weight or whether partial credit is awarded for near-correct responses. This lack of clarity can make it difficult to interpret results with confidence. Greater openness about scoring algorithms would enhance trust and help schools better understand the relationship between instruction and assessment outcomes.

Financial considerations also influence the implementation of the SBAC. Developing and maintaining computer-adaptive testing systems requires significant investment in infrastructure, training, and software maintenance. Wealthier districts are better positioned to absorb these costs, while underfunded schools may struggle to keep pace. This economic disparity underscores a recurring theme in American education—the uneven distribution of resources and opportunities.

Another dimension of the SBAC’s impact involves its relationship with teaching philosophy. When tests evolve, teaching inevitably follows. The emphasis on analytical thinking and cross-disciplinary reasoning encourages educators to design lessons that mirror the skills tested. Ideally, this alignment fosters deeper learning and more meaningful engagement with content. Yet some critics caution that excessive alignment can lead to teaching to the test, narrowing the curriculum and stifling creativity. Achieving a balance between preparation and exploration remains one of the most delicate challenges for modern educators.

One of the SBAC’s most ambitious goals is to create an assessment that not only evaluates students but also strengthens instruction. The detailed performance reports generated by the test can serve as diagnostic tools, revealing trends at the classroom, school, and district levels. When used thoughtfully, this information can guide interventions, shape professional development programs, and inform curriculum design. However, the utility of these reports depends on how effectively they are interpreted and applied within educational communities.

The cultural and psychological dimensions of testing also deserve attention. For many students, standardized assessments evoke anxiety and pressure, which can distort performance and obscure true ability. The SBAC’s computer-adaptive design seeks to mitigate this by presenting questions that align more closely with a student’s skill level, thus reducing frustration and boredom. Yet the awareness that results carry significant academic implications can still generate stress, especially in environments where test outcomes are tied to school rankings or teacher evaluations.

The long-term success of the SBAC will depend on how well it harmonizes its technical sophistication with the human realities of learning. Education is not a purely mechanical process; it involves emotion, curiosity, and interpersonal connection. Tests can measure achievement, but they cannot replicate the experience of discovery that defines genuine understanding. As such, the SBAC should be viewed not as a final judgment but as one instrument among many for fostering educational growth.

The Origins and Purpose of the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium arose from a national movement to reform standardized testing and align educational practices with the expectations of the Common Core State Standards. Its establishment represented a significant turning point in the philosophy of academic evaluation in the United States. The concept behind it was to create an equitable testing system that could consistently measure student achievement across multiple states while accommodating the complexity of modern learning.

Before the emergence of the consortium, standardized assessments varied drastically among states. These disparities made it difficult to compare student performance or identify consistent academic benchmarks. Some states had rigorous exams with complex analytical components, while others relied on assessments that measured rote memorization. This inconsistency generated confusion among educators, policymakers, and parents who sought to understand how students from different regions compared in terms of academic readiness.

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium was conceived as a corrective measure to these inconsistencies. Its architects aimed to create a test that measured not only academic knowledge but also the cognitive skills necessary for success in an increasingly globalized and technology-driven world. This new testing model would emphasize critical thinking, evidence-based reasoning, and problem-solving—all central components of the Common Core philosophy.

The origins of the consortium date back to a period of educational introspection in the early 21st century. Federal and state leaders recognized that the traditional metrics of assessment were not capturing the evolving skills required in higher education and the modern workforce. Employers and universities alike reported that many graduates lacked the ability to analyze complex information, think creatively, and communicate effectively. These findings underscored a widening gap between what schools taught and what society demanded.

In response, educational reformers began to advocate for a unified set of standards designed to raise academic expectations and ensure that students, regardless of geographic location, had access to a comparable quality of education. From this initiative emerged two major assessment consortia: the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC). While both shared similar objectives, the SBAC distinguished itself through its commitment to computer-adaptive testing and its extensive collaboration among participating states.

The structure of the consortium was intentionally designed to be cooperative. Member states pooled resources and expertise to develop a comprehensive testing system grounded in research and validated through pilot studies. This collective approach reflected a broader belief that education should not operate in isolation; rather, it should benefit from shared innovation and collective responsibility. By working together, the participating states aimed to construct a testing model that was both rigorous and flexible enough to evolve alongside educational practices.

One of the most striking features of the SBAC’s development was its emphasis on technological integration. Traditional testing methods—paper-based, manually scored, and logistically cumbersome—were no longer sufficient to meet the demands of large-scale educational assessment. The move toward digital testing represented both a practical and philosophical shift. On a practical level, online testing streamlined administration, scoring, and data collection. On a philosophical level, it symbolized a transition toward 21st-century learning environments in which digital literacy is integral to academic success.

Computer-adaptive testing lies at the heart of the SBAC’s methodology. Unlike traditional exams that present the same set of questions to every student, adaptive tests modify their difficulty in real time based on a student’s responses. This dynamic adjustment produces a more precise estimate of ability, reducing the likelihood that high-achieving students will find the test too easy or that struggling students will find it overwhelmingly difficult. The result is a more individualized testing experience that aligns with each learner’s cognitive trajectory.

This approach also offers a deeper form of data analysis. Because the SBAC tracks not just whether an answer is correct but also the sequence and reasoning patterns leading to that answer, educators gain a richer understanding of how students think. This analytical depth enables schools to identify specific conceptual gaps and adjust instruction accordingly. The data collected through this process can reveal broader trends across grade levels, subject areas, and demographic groups, allowing policymakers to address systemic inequities in education.

The consortium’s focus on fairness and inclusivity reflects an awareness of the diverse needs within the American student population. Testing accommodations were designed for students with disabilities, English language learners, and those from varied socioeconomic backgrounds. The goal was to create an assessment environment in which all students had an equal opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. This commitment to equity also extended to the content of the tests, which underwent extensive review to minimize cultural or linguistic bias.

The purpose of the SBAC extends beyond the simple measurement of knowledge acquisition. It serves as a diagnostic instrument that informs instruction, curriculum design, and policy decisions. Each test result contributes to a larger body of data used to evaluate educational effectiveness at multiple levels—individual, classroom, school, district, and state. In doing so, the SBAC helps identify which instructional strategies yield the best outcomes and where resources should be allocated to support improvement.

Moreover, the SBAC represents an attempt to bridge the gap between K–12 education and postsecondary readiness. The consortium’s assessments were designed with input from higher education institutions to ensure that performance benchmarks accurately reflected the skills needed for success in college-level coursework. This alignment is particularly important given that one of the persistent criticisms of earlier testing systems was their failure to predict college readiness accurately.

By grounding its design in the principles of the Common Core Standards, the SBAC embodies a philosophy that values depth of understanding over breadth of content. The test emphasizes reasoning, evidence, and application rather than the mere recall of facts. For example, in English language arts, students are required to analyze passages, infer meanings, and construct coherent arguments supported by textual evidence. In mathematics, they must not only perform calculations but also explain the reasoning behind their solutions and apply mathematical principles to real-world scenarios.

This shift represents a broader pedagogical transformation within American education. The traditional model of instruction—where teachers transmitted information and students regurgitated it on exams—has gradually given way to a model that prioritizes inquiry, collaboration, and critical thought. The SBAC serves as both a reflection and a reinforcement of this transition. By assessing students on their ability to synthesize information and draw conclusions, the test encourages teachers to adopt instructional methods that nurture analytical thinking.

Despite its progressive aims, the SBAC has faced a spectrum of challenges since its inception. The first major issue involves technological accessibility. Not all schools have the same level of digital infrastructure, and disparities in broadband connectivity or hardware availability can affect test administration. In some regions, limited access to functioning computers or reliable internet connections has led to delays, interruptions, and frustration among students and staff alike.

The consortium recognized these challenges early on and encouraged states to invest in upgrading their technological capacity. However, such improvements require significant financial resources, and not all districts are equally equipped to meet these demands. The result is a persistent imbalance between schools that can fully embrace computer-adaptive testing and those that must contend with logistical hurdles. This discrepancy raises important questions about the relationship between technology and educational equity.

Another challenge lies in public perception. Standardized testing, regardless of format, often elicits skepticism from parents, teachers, and students. Many perceive such assessments as high-stakes exercises that reduce education to a numerical score. The SBAC’s developers sought to counter this perception by emphasizing the test’s diagnostic and formative value rather than its punitive potential. Yet changing entrenched attitudes about testing culture remains an uphill battle.

Educators also express concern about the time required to administer the SBAC. Because of its adaptive nature and complex question design, the test can be lengthy, leading to student fatigue. Balancing the need for comprehensive assessment with the realities of classroom schedules continues to be a logistical challenge. Schools must allocate multiple days for testing, which can disrupt instructional flow and reduce the time available for non-tested subjects or enrichment activities.

The psychological dimension of testing cannot be ignored either. Students approach exams with varying levels of confidence and anxiety, both of which can influence outcomes. Computer-adaptive testing introduces an additional layer of complexity because students cannot predict how difficult the next question will be. This uncertainty can create tension, particularly for those who equate difficulty with failure. Educators must therefore provide reassurance and context, emphasizing that fluctuating question difficulty is a normal part of the process, not an indicator of performance.

From an instructional standpoint, the SBAC provides teachers with an unprecedented level of data granularity. Instead of a single score that vaguely reflects performance, educators receive detailed profiles outlining student proficiency across multiple skill domains. This information can guide interventions, enrich lessons, and foster individualized learning plans. For instance, if a student demonstrates strong reading comprehension but weak inferential reasoning, teachers can target instruction toward improving that specific cognitive skill.

However, the effectiveness of such data-driven instruction depends heavily on teacher training. Interpreting complex assessment reports requires familiarity with statistical concepts and a clear understanding of how testing algorithms function. Without proper professional development, the wealth of information generated by the SBAC may remain underutilized. The consortium and participating states have invested in training initiatives to bridge this knowledge gap, but implementation varies widely across districts.

Another area of ongoing debate concerns the balance between state oversight and local autonomy. While the SBAC establishes consistent standards, education remains primarily a local endeavor. Some districts have expressed concern that nationalized testing frameworks may erode local control over curriculum design. Others argue that consistent benchmarks are necessary to ensure accountability and equity. Navigating this tension requires careful governance and open communication between policymakers, educators, and communities.

The SBAC’s influence extends beyond the confines of the test itself. Its introduction has prompted schools to reevaluate their instructional priorities and to align lesson plans with the competencies it measures. In this way, the test indirectly shapes curriculum design, teacher training, and classroom dynamics. While this alignment can lead to improved coherence between instruction and assessment, it also risks narrowing educational focus to tested subjects at the expense of creativity and exploration.

The Framework and Structure of the Smarter Balanced Assessment

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium operates on a framework that intertwines innovation, equity, and pedagogical rigor. Its design reflects a fusion of research-based principles and technological advancements, culminating in an assessment system intended to evaluate the multidimensional aspects of learning. At its core, the SBAC framework seeks to measure not only the mastery of academic standards but also the underlying cognitive processes that support critical thinking, analysis, and synthesis. The structural foundation of the test is intentionally layered to mirror the complexity of real-world problem-solving.

Unlike traditional assessments that adhere to static question sets, the SBAC employs a computer-adaptive model. This model is both dynamic and diagnostic, adjusting the difficulty of questions based on each student’s responses. The system uses sophisticated algorithms to calibrate the next question in real time, creating a tailored testing experience that reflects individual proficiency levels. This adaptive approach ensures that students encounter questions that are neither too simple nor too advanced, thus maintaining engagement and providing a more accurate reflection of their capabilities.

In practice, the adaptive framework functions much like a continuous feedback loop. Each response provides data that influences subsequent questions, resulting in a unique test path for every student. For example, a correct answer to a mid-level question might prompt a more challenging one, while an incorrect response could trigger a question designed to probe foundational understanding. This iterative process generates a nuanced portrait of each learner’s strengths and weaknesses. Rather than offering a binary measure of right or wrong, it evaluates the continuum of understanding, identifying both mastery and misconception.

The SBAC structure encompasses two primary domains: English Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics. Each domain contains multiple subcategories designed to assess distinct competencies aligned with the Common Core State Standards. Within ELA, the focus areas include reading comprehension, writing, listening, and research skills. Students must analyze texts, interpret themes, evaluate evidence, and construct reasoned arguments. The test emphasizes textual analysis and evidence-based reasoning, requiring students to engage deeply with content rather than merely recalling information.

The mathematics portion of the SBAC similarly moves beyond computational fluency to assess conceptual understanding and application. Students encounter problems that demand logical reasoning, pattern recognition, and the ability to apply mathematical principles to practical scenarios. Instead of performing repetitive calculations, they must explain their reasoning, interpret data, and connect mathematical ideas to real-world contexts. This design aligns with the overarching educational shift toward fostering problem-solving and higher-order cognitive skills.

A defining feature of the SBAC’s framework is the inclusion of performance tasks—extended activities that integrate multiple skills and knowledge areas. These tasks require students to engage in sustained reasoning, analysis, and written communication. For instance, a performance task in ELA might ask students to read several related texts, synthesize information, and compose an essay defending a specific viewpoint using evidence from the readings. In mathematics, performance tasks might involve interpreting data from graphs, developing a model, or justifying a solution through logical argumentation.

Performance tasks serve a dual purpose: they assess the application of knowledge and mirror the types of challenges students are likely to encounter in higher education or professional environments. By requiring integration across content areas, these tasks transcend rote learning and simulate authentic intellectual inquiry. This component of the SBAC exemplifies the consortium’s commitment to cultivating versatile learners capable of navigating complex problems with adaptability and insight.

Another structural element central to the SBAC is its reliance on digital interactivity. The test’s computer-based format allows for question types that would be impossible in a paper exam. Students may drag and drop responses, highlight textual evidence, or manipulate virtual objects to demonstrate understanding. This interactivity enhances engagement and broadens the spectrum of skills that can be assessed. It also reflects an acknowledgment that digital literacy has become an essential component of modern education.

Despite these innovations, the SBAC framework has encountered challenges related to technological execution. Variations in hardware quality, internet connectivity, and user familiarity can affect the testing experience. Some schools, particularly those in underfunded districts, struggle to provide the necessary infrastructure to ensure smooth administration. These disparities highlight the persistent issue of digital inequity in education—a challenge that must be addressed if the SBAC’s mission of fairness is to be fully realized.

Scoring within the SBAC framework operates through a combination of automated algorithms and human evaluation. Multiple-choice and short-response items are typically scored by computer, ensuring rapid and consistent processing. More complex responses, such as essays or performance tasks, require human scorers trained to apply detailed rubrics. These rubrics focus on coherence, reasoning, accuracy, and evidence integration rather than superficial features. The hybrid scoring model allows the consortium to balance efficiency with qualitative judgment, ensuring that student work receives both analytical precision and interpretive fairness.

The development of these scoring rubrics reflects the consortium’s attention to reliability and validity. Every rubric undergoes rigorous testing to ensure that scorers interpret criteria consistently. Calibration sessions, blind scoring, and statistical analyses are used to maintain inter-rater reliability. This meticulous process underscores the importance of fairness and objectivity in large-scale assessment. A misalignment between rubric design and scorer interpretation could distort outcomes, undermining the test’s credibility.

Each test administration cycle contributes to an expansive data repository that informs continuous improvement. Item analyses identify which questions effectively differentiate between proficiency levels and which require revision. Questions that exhibit bias or inconsistent performance are removed or restructured. Over time, this iterative refinement enhances the test’s precision and fairness. The adaptive algorithms themselves also evolve, drawing upon vast datasets to improve predictive accuracy and question calibration.

The SBAC’s framework also emphasizes accessibility and inclusivity. Recognizing the diversity of student needs, the consortium designed a suite of accommodations and supports embedded directly into the testing platform. These features include text-to-speech options, adjustable font sizes, high-contrast displays, glossaries, and language translations. Such tools ensure that students with disabilities, visual impairments, or linguistic challenges can engage with the content equitably. Importantly, these accommodations are seamlessly integrated so that they do not disrupt the testing experience or stigmatize users.

The notion of accessibility extends beyond physical or linguistic barriers. It encompasses cognitive accessibility as well. The SBAC’s adaptive nature helps ensure that students are neither overwhelmed by excessively difficult questions nor disengaged by overly simple ones. This adaptive equilibrium supports sustained focus and confidence, particularly among students who might otherwise feel alienated by standardized testing environments.

At the policy level, the SBAC’s structure facilitates large-scale data analysis for educational improvement. The results provide insights not only into individual performance but also into broader patterns that can inform curriculum development, teacher training, and policy initiatives. For example, aggregated data may reveal that students across a state struggle with certain types of reasoning or literacy skills. Policymakers can then use these insights to allocate resources toward targeted interventions.

For educators, the structure of the SBAC encourages a pedagogical shift toward inquiry-based and evidence-driven instruction. Because the test rewards reasoning and synthesis, teachers are incentivized to design lessons that cultivate these abilities. Classroom activities increasingly emphasize analytical writing, problem-solving, and collaborative exploration. The ripple effect of this transformation extends beyond test preparation, influencing the overall culture of learning.

While the SBAC framework is grounded in consistency, it is not rigid. One of its distinguishing qualities is its capacity for evolution. Feedback from educators, students, and researchers continuously shapes revisions to content and format. The consortium’s iterative design philosophy mirrors the process of learning itself—a continuous cycle of testing, reflection, and refinement. This adaptability ensures that the assessment remains relevant in an ever-changing educational landscape.

Nonetheless, the process of continual evolution presents certain complications. Frequent updates require schools to adjust instructional materials and retrain staff, which can strain resources. Teachers may feel pressured to stay abreast of each modification while maintaining classroom stability. Moreover, repeated revisions can cause confusion among parents and students who struggle to keep pace with changing expectations. Striking a balance between progress and consistency remains one of the consortium’s ongoing challenges.

The structure of the SBAC also encompasses comprehensive reporting mechanisms. After each test administration, schools receive detailed data summaries that break down performance by content area, skill domain, and proficiency level. These reports are designed to be transparent and actionable, providing educators with concrete insights into where students excel and where improvement is needed. The clarity of these reports is crucial; without accessible interpretation, even the most sophisticated data loses its value.

In designing its reporting systems, the consortium prioritized clarity and usability. Graphical displays, performance bands, and narrative descriptions help translate complex data into understandable insights. The goal is to make assessment results not merely a summation of performance but a catalyst for reflection and growth. Teachers can use this information to identify patterns, adapt instruction, and set measurable goals for student progress.

The comprehensive nature of the SBAC’s structure also invites broader reflection on the philosophy of assessment itself. The framework challenges conventional notions of testing as an endpoint. Instead, it positions assessment as an integral part of learning—a diagnostic tool that informs teaching and fosters growth. By situating assessment within a cycle of continuous improvement, the SBAC redefines the relationship between evaluation and education.

The Educational Philosophy Behind the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium stands not only as a technological and administrative innovation but also as a philosophical reimagining of what education and learning assessment mean in a rapidly evolving world. Beneath its structure lies a deep pedagogical rationale that seeks to reshape how educators, students, and policymakers define achievement. This philosophy diverges from traditional models of standardized testing by focusing less on the mere acquisition of facts and more on the cultivation of thought, reasoning, and the ability to apply knowledge in diverse contexts.

At the heart of this philosophy is the conviction that learning is a dynamic, reflective process rather than a static accumulation of information. The Smarter Balanced Assessment system, by design, prioritizes comprehension, interpretation, and synthesis over memorization. Its creators envisioned an evaluative tool that mirrors authentic intellectual activity, where students engage with ideas, draw inferences, and defend positions based on evidence. This emphasis on cognitive depth aligns with the broader educational movement that advocates for cultivating lifelong learners capable of navigating complexity with agility and discernment.

The roots of this philosophy can be traced to constructivist theories of learning, which posit that knowledge is actively constructed through experience, dialogue, and reflection. According to this perspective, education should not be confined to the transmission of information from teacher to student. Instead, it should foster environments in which learners explore, question, and connect new ideas to prior understanding. The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium integrates this principle by crafting assessments that require interpretation and reasoning rather than simple recall. For example, when a student encounters a passage in the English Language Arts section, they are not merely asked to identify a main idea but to analyze the author’s intent, evaluate the use of evidence, and synthesize information across multiple texts.

Similarly, the mathematics component reflects a shift from mechanical computation toward conceptual reasoning. Students are encouraged to demonstrate understanding through problem-solving, pattern recognition, and the articulation of thought processes. They might be presented with a scenario involving data interpretation or spatial reasoning, requiring them to translate mathematical ideas into real-world applications. This form of assessment moves beyond verifying procedural knowledge to examining whether students grasp the underlying principles governing their work.

The philosophical underpinnings of the consortium also rest on the notion of equity in education. The SBAC’s adaptive model is not merely a technical choice but a moral one, designed to provide every student with a fair opportunity to succeed. Traditional one-size-fits-all tests have long been criticized for favoring certain groups of students—those with stronger test-taking strategies, greater access to preparatory resources, or backgrounds that align with the cultural assumptions embedded in exam content. By contrast, the SBAC’s computer-adaptive testing tailors the experience to each individual, thereby reducing the disadvantage for students who might otherwise struggle with fixed-difficulty exams.

This focus on fairness reflects a deeper philosophical commitment to inclusivity. Learning, in its truest sense, is an inherently human process that should accommodate diversity rather than conform to uniformity. The consortium’s attention to accessibility features—such as text-to-speech support, visual contrast options, and multilingual glossaries—demonstrates an awareness that equitable education cannot exist without attention to individual needs. In this respect, the SBAC represents an attempt to translate educational ideals of inclusion and differentiation into tangible, operational realities.

The SBAC’s philosophical framework also embraces the concept of formative learning—education as a continuous journey of improvement rather than a series of isolated outcomes. The test’s detailed feedback mechanism provides teachers with insights into student progress, allowing them to identify specific areas for growth. This data-driven reflection supports a culture of ongoing refinement, where assessment becomes a dialogue between educator and learner rather than a unilateral judgment. It reinforces the idea that testing should inform teaching, guiding instruction toward areas that require reinforcement or enrichment.

Such an approach contrasts sharply with older models of standardized assessment, which were often summative and final in nature. In those systems, tests functioned as endpoints—defining achievement in static terms and offering little room for recalibration. The Smarter Balanced philosophy, on the other hand, positions assessment as part of a cyclical process that intertwines with learning itself. It recognizes that intellectual growth is iterative, shaped by mistakes, feedback, and reflection.

Underlying the consortium’s philosophy is also a belief in transparency and accountability, not as mechanisms of control, but as tools for empowerment. By providing educators with detailed, disaggregated data, the SBAC enables evidence-based decision-making at both the classroom and administrative levels. When used thoughtfully, this transparency fosters trust among teachers, parents, and policymakers, encouraging collaboration toward shared educational goals. However, this trust hinges on the responsible interpretation of data—recognizing that numbers alone do not define human potential but can illuminate pathways for nurturing it.

This balance between data and humanity encapsulates one of the most nuanced aspects of the SBAC’s educational philosophy. In a data-saturated era, there is a temptation to equate measurement with meaning. The consortium resists this reductionist impulse by asserting that data should serve understanding rather than replace it. The intent is to use quantitative insights to enhance qualitative learning experiences—to let numbers guide, not dictate, educational priorities.

Another critical tenet of the consortium’s philosophy is the emphasis on readiness for life beyond school. The SBAC’s assessments are designed to measure skills that transcend classroom boundaries, preparing students for college, careers, and civic engagement. In this sense, the test embodies the concept of applied intelligence—the ability to transfer learning from one context to another. Students are expected to analyze information, collaborate with others, and communicate ideas effectively, all of which are competencies essential in an interconnected global society.

This broader conception of readiness aligns with twenty-first-century educational paradigms that emphasize adaptability, creativity, and critical literacy. The world students are entering demands more than content mastery; it requires the capacity to synthesize knowledge across disciplines, to innovate, and to engage ethically with diverse perspectives. The SBAC’s integrated design encourages the cultivation of these capacities, reflecting a holistic vision of education that extends beyond traditional academic boundaries.

Furthermore, the consortium’s philosophy embraces the notion that assessment should inspire learning rather than inhibit it. For decades, standardized testing has been associated with stress, competition, and fear of failure. The Smarter Balanced Assessment seeks to shift this perception by reframing tests as opportunities for demonstration rather than judgment. Through adaptive difficulty and responsive feedback, the system aims to create an experience that challenges students appropriately while affirming their progress. By encountering questions calibrated to their ability level, students can engage more meaningfully with the content and develop confidence in their intellectual abilities.

The philosophical orientation of the SBAC also resonates with the principle of interconnectivity—both within subjects and across the broader educational ecosystem. Knowledge, in this framework, is not compartmentalized but fluid. The assessments reflect this by integrating reading, writing, mathematics, and reasoning into cohesive tasks. A student might analyze a passage in English that contains data elements, requiring mathematical interpretation, or respond to a mathematical prompt that demands written justification. This cross-disciplinary approach echoes the complexity of real-life problem-solving, where challenges seldom fit neatly into singular categories.

The integration of disciplines represents more than a pedagogical strategy; it reflects an epistemological stance about how knowledge operates in the world. The consortium’s philosophy suggests that genuine understanding arises not from isolated memorization but from the synthesis of diverse ideas into coherent meaning. Such a view encourages students to see connections, recognize patterns, and apply insights across multiple domains—a skill set increasingly valuable in an era defined by information abundance and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Beyond its direct implications for students, the Smarter Balanced philosophy also redefines the role of educators. Teachers are no longer seen merely as transmitters of knowledge but as facilitators of inquiry and mentors in intellectual growth. The SBAC’s detailed reporting systems empower educators to make informed decisions, tailoring instruction to the unique needs of their students. This dynamic transforms assessment from an external imposition into a shared tool for reflection and progress. When properly integrated, it fosters a collaborative relationship between teacher and student, where both engage in the continuous pursuit of understanding.

Critically, the consortium’s educational philosophy acknowledges the emotional and ethical dimensions of learning. Education is not solely about cognitive advancement; it is also about cultivating empathy, resilience, and integrity. By emphasizing fairness, inclusivity, and reflection, the SBAC implicitly advocates for a humane model of assessment—one that honors individuality while maintaining rigor. The test’s adaptability ensures that each student encounters challenges suited to their developmental stage, reinforcing the principle that growth should be measured relative to potential, not conformity.

However, the implementation of this philosophy faces real-world constraints. The ideals of inclusivity and adaptability often collide with logistical limitations, financial pressures, and policy mandates. Schools with fewer resources may struggle to meet the technological and training requirements necessary for successful test administration. In such cases, the lofty aspirations of the SBAC can appear out of reach, prompting critical discussions about educational equity and systemic reform. Yet, even amid these challenges, the philosophical framework remains a guiding compass—an aspirational model for what assessment can become when guided by vision rather than convenience.

The SBAC’s approach also reveals a subtle but profound shift in how success is conceptualized. Instead of treating performance as a static endpoint, success becomes a narrative of progress, resilience, and reflection. This narrative resists the binary logic of pass and fail, acknowledging that learning is often non-linear and deeply contextual. Students may excel in certain domains while struggling in others, and such variability is recognized as part of the natural rhythm of intellectual development. By adopting this holistic view, the SBAC moves closer to an authentic portrayal of human learning.

The Implementation Challenges and Realities of the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium emerged as an ambitious initiative designed to modernize how learning is measured and interpreted. Its conceptual framework promised adaptability, inclusivity, and precision, yet translating these ideals into practice has proven to be a formidable challenge. Implementation across diverse educational landscapes has illuminated the complexity of standardization within systems marked by inequality, technological disparity, and philosophical divergence.

The deployment of the Smarter Balanced Assessment across school districts required a convergence of resources, infrastructure, and human adaptability. At first glance, the test’s computer-based nature appeared to signify progress—a movement toward efficiency, speed, and modernity. Yet, beneath that surface, the transition revealed fractures within the educational ecosystem. Schools varied widely in their capacity to adopt the new system. Wealthier districts, equipped with reliable technology and trained staff, transitioned smoothly. Others, particularly those in rural or underfunded regions, encountered persistent barriers.

One of the most conspicuous challenges was technological access. For many schools, especially in communities with limited broadband infrastructure, even maintaining stable connectivity during testing became an ordeal. Students experienced delays, crashes, and interruptions that affected both concentration and performance. Teachers and administrators faced logistical chaos as they scrambled to troubleshoot problems in real time. Such difficulties revealed that the supposed neutrality of computer-based testing was, in reality, shaped by socioeconomic and geographic inequalities. The promise of fairness—central to the consortium’s mission—was compromised whenever technology dictated opportunity.

The digital divide also raised questions about familiarity. Students accustomed to frequent computer use navigated the interface intuitively, while those with limited exposure faced an added cognitive burden unrelated to academic ability. Tasks requiring drag-and-drop actions, digital highlighting, or on-screen calculators became more about mastering mechanics than demonstrating knowledge. In effect, the assessment inadvertently measured technological literacy alongside academic competence. This overlap underscored a subtle irony: the very innovation designed to equalize opportunity risked amplifying disparity.

Training educators represented another significant dimension of the implementation challenge. The Smarter Balanced Assessment demanded not only technical proficiency but also conceptual understanding. Teachers had to learn how to interpret adaptive results, integrate data into instruction, and realign lesson plans to reflect the competencies measured by the test. While professional development programs were introduced, their quality and depth varied substantially. Some educators embraced the transition, viewing it as an opportunity for pedagogical evolution. Others, feeling overwhelmed by shifting expectations and limited support, expressed frustration and skepticism.

These mixed reactions reflected a broader tension between innovation and inertia in educational systems. Change, no matter how progressive in intention, can falter when imposed without adequate scaffolding. The consortium’s rollout highlighted that transformation in education must be accompanied by time, communication, and cultural readiness. Without these, even the most carefully designed systems risk alienating the very practitioners they rely on.

Another layer of complexity emerged from policy interpretation. States and districts retained flexibility in how they implemented the Smarter Balanced framework, leading to variations in timing, structure, and scoring application. While this autonomy allowed local customization, it also produced inconsistency. Students across different regions experienced divergent versions of what was ostensibly a standardized test. Moreover, the integration of SBAC results into accountability systems—such as teacher evaluations and school performance metrics—sparked controversy. Critics argued that using high-stakes testing for such purposes distorted educational priorities, encouraging teaching to the test rather than nurturing genuine understanding.

The assessment’s adaptive model also posed conceptual challenges for educators and policymakers. Because the test adjusts in difficulty based on student responses, two learners can receive different sets of questions, making direct comparison of scores less intuitive. While this approach personalizes assessment, it complicates statistical interpretation. Teachers seeking to analyze results across classes or districts found themselves navigating intricate data systems that required technical and analytical literacy far beyond traditional grading practices.

From a logistical standpoint, the test’s administration schedule strained resources. Schools had to allocate computer labs for extended periods, coordinate proctoring staff, and accommodate make-up sessions for absent students. These demands disrupted regular classroom routines, often displacing instructional time. Furthermore, the need for constant technical supervision—ensuring that software functioned, servers remained stable, and student data stayed secure—added another layer of operational complexity.

Beyond logistics, the emotional and psychological dimensions of the transition were equally significant. For many students, the unfamiliar digital interface and the high stakes associated with standardized assessments contributed to anxiety. Teachers, already managing packed curricula and accountability pressures, struggled to balance preparation for the test with maintaining holistic learning environments. Parents, witnessing the growing emphasis on assessment, expressed concern that education was becoming overly mechanized, reducing creativity and joy in learning.

The Smarter Balanced Consortium faced the formidable task of addressing these human concerns while maintaining its commitment to innovation. Communication became a central challenge. The intent behind the test—to measure deeper learning and support growth—was often overshadowed by misunderstanding or misinformation. Where schools lacked clear messaging, resistance grew. Communities questioned the purpose and value of another standardized exam, particularly one associated with the already controversial Common Core framework.

Furthermore, financial realities shaped the trajectory of implementation. Transitioning from paper-based to computer-based testing required substantial investment in technology, maintenance, and training. Districts operating under tight budgets faced difficult decisions—redirecting funds from instructional programs or extracurricular activities to meet testing requirements. These trade-offs intensified debates about educational priorities and equity. Could a system that demanded such investment truly serve all students equally, or would it inadvertently deepen existing divides?

Despite these obstacles, certain aspects of the SBAC rollout demonstrated resilience and adaptability. Many educators discovered value in the rich data generated by the assessment. Unlike older tests that provided limited feedback, the Smarter Balanced reports offered nuanced insights into student strengths and weaknesses. Teachers who learned to interpret this data effectively could design targeted interventions, differentiating instruction with greater precision. Over time, schools that embraced data-driven reflection began to see improvement in instructional alignment and student engagement.

Nevertheless, success depended heavily on context. In schools with supportive leadership, adequate infrastructure, and a collaborative culture, the SBAC functioned as intended—a tool for growth and reflection. In less prepared environments, it became a source of frustration, widening the gap between aspiration and reality. This dichotomy revealed that innovation cannot be divorced from systemic readiness. The same technology that empowers one classroom can overwhelm another if foundational supports are absent.

Cultural perception also played a role in shaping implementation outcomes. In communities that valued experimentation and embraced change, the Smarter Balanced Assessment was viewed as a forward-looking reform. In others, particularly those fatigued by decades of shifting policies, it was received with skepticism. For many educators, the consortium represented yet another reform initiative destined to fade under political and bureaucratic turnover. This perception—fueled by past experiences of transient educational trends—created a climate of guarded compliance rather than enthusiastic participation.

Moreover, questions about data privacy and security complicated implementation. The digital nature of the assessment required the collection and storage of sensitive student information. Concerns emerged about how this data might be used, who had access to it, and whether it could be safeguarded against breaches. In an era increasingly aware of digital vulnerability, such apprehensions were not unfounded. The consortium and participating states had to invest in robust cybersecurity measures and transparent policies to reassure educators and families alike.

The process of implementing the Smarter Balanced Assessment also underscored the importance of patience in educational reform. Large-scale systemic change rarely yields immediate results. Early missteps and frustrations, though disheartening, often serve as catalysts for refinement. In some regions, initial technical difficulties prompted investments in digital literacy and infrastructure that ultimately benefited broader educational initiatives. Likewise, the demands of interpreting complex assessment data encouraged a new generation of teachers to develop analytical skills that enhanced their instructional practice beyond testing contexts.

Nevertheless, the challenges remain substantial. Achieving consistency across districts with vastly different resources continues to be a formidable undertaking. Ensuring that the test’s adaptive algorithm functions equitably for diverse populations requires constant recalibration and monitoring. Addressing teacher workload, student anxiety, and community trust necessitates ongoing dialogue and transparency. The consortium’s evolution, therefore, depends not only on technical adjustments but also on sustained cultural engagement within education.

The realities of implementation reveal a deeper truth about reform: no assessment, however innovative, can exist in isolation from the conditions that surround it. The Smarter Balanced Assessment’s potential lies not merely in its design but in the collective willingness of educators, policymakers, and communities to nurture its vision. Where collaboration thrives, the test becomes a catalyst for reflection and growth. Where fragmentation persists, it risks becoming another instrument of division.

The Future of the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and the Evolving Landscape of Learning

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium occupies a pivotal position in the broader transformation of educational systems. Its emergence signified a conscious shift toward assessments that prioritize critical thinking, reasoning, and applied knowledge. Yet the true measure of its success will not rest solely on its design or implementation, but on how it adapts to the evolving demands of education in an era defined by technological acceleration and cultural change. The consortium, though rooted in early twenty-first-century reforms, must now confront questions that transcend the boundaries of its original mandate.

Education today is no longer a static institution confined within classroom walls. It exists within a fluid continuum of information, interaction, and innovation. Students encounter knowledge across digital platforms, through social discourse, and via global networks that redefine what it means to learn. The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium must, therefore, evolve alongside this new reality, ensuring that its assessments remain relevant to the way knowledge is acquired, processed, and applied in the modern world.

The first and most pressing challenge facing the consortium’s future is adaptability to technological change. When it was first introduced, the notion of computer-based testing represented innovation. Now, technology has advanced to encompass artificial intelligence, immersive learning environments, and adaptive feedback systems capable of real-time analysis. These advancements open possibilities for transforming the Smarter Balanced model into something far more dynamic. Rather than a single annual assessment, it could evolve into a continuous learning companion—one that interacts with students’ progress throughout the academic year, providing instant feedback and adaptive guidance.

Such a transformation would require not only technological sophistication but also philosophical clarity. The purpose of assessment must remain educational, not purely algorithmic. Machines can process data, but they cannot yet fully grasp the nuances of human thought, creativity, or emotion. As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly integrated into educational systems, the consortium must guard against the reduction of learning to numerical abstraction. The human element—the teacher’s intuition, the student’s curiosity, the dialogue that animates classrooms—must remain central. The goal should be harmony between data and humanity, where technology amplifies insight without overshadowing it.

Another significant factor shaping the consortium’s future is the diversification of learning pathways. Traditional schooling, once the dominant mode of education, now coexists with online academies, micro-credentialing platforms, apprenticeships, and community-based learning models. This diversity challenges the very notion of standardized assessment. How can a single test, however adaptive, account for the multiplicity of ways in which knowledge manifests? The future may call for a network of interconnected assessments that reflect distinct competencies—collaboration, creativity, ethical reasoning, digital fluency—rather than a singular, monolithic exam.

In this emerging landscape, the consortium could evolve into a framework for credentialing multidimensional learning. Imagine an assessment system that recognizes a student’s project in environmental science, their coding skills demonstrated through digital prototypes, and their narrative analysis presented through multimedia storytelling. Each component would form part of a holistic portrait of ability, offering a richer, more authentic representation of learning. This vision aligns with global movements toward competency-based education, which emphasize mastery and application over memorization.

Equity will remain a defining concern as the Smarter Balanced Assessment moves forward. While its adaptive model was designed to accommodate diverse learners, equity in practice requires constant vigilance. The digital divide persists, manifesting in new forms as technology evolves. Access to reliable devices, high-speed internet, and supportive learning environments cannot be assumed. Moreover, biases in data algorithms can inadvertently reproduce systemic inequalities. The consortium’s future will depend on its capacity to ensure that innovation does not become another vector of exclusion.

Achieving this will require more than technical fixes; it demands ethical leadership and collaborative design. Educators, technologists, psychologists, and sociologists must work in concert to refine the principles that guide assessment development. The voices of students themselves—those most affected by the outcomes—should be integral to the process. Involving learners in the design of future assessments would not only enhance fairness but also cultivate a sense of agency, transforming testing from an imposed requirement into a participatory act of reflection.

The evolving role of teachers also carries profound implications for the consortium’s trajectory. As artificial intelligence and automation assume greater roles in educational data management, the human educator’s function will shift toward mentorship, facilitation, and ethical guidance. The Smarter Balanced system must adapt to support this transformation. Rather than serving as a distant evaluator, it can become an ally to educators, offering real-time insights that empower them to tailor instruction with precision. Through intelligent dashboards and narrative-based reporting, teachers could gain a deeper understanding of their students’ cognitive and emotional development.

However, this integration of technology and pedagogy will necessitate extensive professional learning. Teachers must be equipped not only to interpret complex data but to translate it into meaningful action. The consortium’s future, therefore, lies partly in its ability to foster a symbiotic relationship with professional development frameworks. Assessment literacy—understanding what data reveals and what it conceals—will become an essential skill in the educator’s repertoire.

The cultural dimension of assessment will also play an increasingly influential role. The Smarter Balanced Consortium operates within a society undergoing rapid demographic and ideological transformation. Students bring with them a tapestry of languages, traditions, and worldviews. Future assessments must reflect this diversity not as an obstacle to standardization but as an enrichment of it. Culturally responsive assessment design—where content resonates with varied backgrounds—will be crucial to maintaining relevance and authenticity. By recognizing multiple ways of knowing, the consortium can foster inclusivity that transcends mere accommodation.

Environmental and psychological sustainability form another frontier of consideration. High-stakes testing has long been associated with stress and burnout. Future iterations of the Smarter Balanced model must explore ways to mitigate these effects. Incorporating reflective pauses, creative tasks, or collaborative components could reframe assessment as an empowering experience rather than an anxiety-inducing ordeal. Furthermore, the consortium might embrace ecological responsibility by optimizing testing platforms for minimal resource consumption, aligning educational practice with broader sustainability goals.

The future of the Smarter Balanced Assessment will also be shaped by the shifting relationship between education and the workforce. The boundaries separating academic and professional life continue to blur, and assessments must evolve to capture transferable skills relevant to both domains. The consortium could partner with institutions that focus on workforce readiness, integrating problem-solving scenarios drawn from real-world contexts—engineering challenges, ethical dilemmas, or policy analyses—that mirror the complexity of modern careers. Such alignment would transform testing into a bridge between learning and livelihood, underscoring education’s relevance in an unpredictable economy.

Moreover, the concept of lifelong learning will redefine the consortium’s purpose. In an age where individuals continuously reskill and adapt, assessment cannot remain confined to childhood and adolescence. The Smarter Balanced framework could expand to accommodate learners across all ages, offering modular evaluations that recognize evolving competencies throughout life. This approach would democratize access to credentialing and reaffirm the principle that learning is perpetual, not terminal.

Data integrity and ethical governance will remain foundational to the consortium’s credibility. As digital ecosystems grow more complex, protecting student privacy becomes paramount. The consortium must lead by example in establishing transparent policies that prioritize consent, minimize data collection, and ensure accountability. Ethical stewardship of information will determine public trust in assessment institutions. Any erosion of that trust risks undermining not only the consortium’s legitimacy but the very notion of equitable education.

Beyond logistics and policy, the future of the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium is ultimately philosophical. It must continue to ask fundamental questions about what it means to know, to understand, and to learn. The test’s evolution will mirror society’s shifting conception of intelligence—from narrow definitions rooted in academic performance to broader interpretations that encompass creativity, empathy, collaboration, and ethical discernment. In this sense, the consortium’s role extends beyond measurement; it becomes a mirror reflecting humanity’s educational aspirations.

As education moves deeper into the digital age, the Smarter Balanced Assessment will be called upon to balance precision with compassion, structure with flexibility, and accountability with imagination. Its capacity to do so will depend on its willingness to embrace experimentation. Pilot programs exploring alternative assessments, performance portfolios, or interdisciplinary tasks may point the way toward a more holistic system. The consortium’s greatest strength lies in its ability to evolve—adapting not through radical overhaul but through gradual, thoughtful refinement guided by evidence and empathy.

If it succeeds in this endeavor, the consortium could redefine the global conversation about assessment. Other nations and institutions may look to its model as an example of how technology, inclusivity, and critical pedagogy can coexist. The Smarter Balanced Assessment has already proven that innovation in education is possible when collaboration replaces competition and when curiosity replaces compliance. Its future will depend on whether it continues to embody those values in practice.

Conclusion

The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium represents a significant evolution in how education measures learning, growth, and understanding. More than a testing mechanism, it embodies a philosophical and structural shift toward inclusivity, adaptability, and reflective practice. Its creation sought to balance the precision of technology with the humanity of learning, acknowledging that assessment should illuminate progress rather than define limitation. Through its adaptive model, it has encouraged a more nuanced understanding of student achievement—one that values reasoning, creativity, and application over rote memorization.

Yet, the consortium’s journey also reveals the profound challenges inherent in educational reform. Technological disparities, resource inequities, and divergent interpretations across states continue to shape its effectiveness. The process of implementation has shown that innovation requires more than design; it demands patience, equity, and trust. Despite these obstacles, the Smarter Balanced Assessment has laid the groundwork for a more responsive and equitable system of evaluation—one capable of evolving alongside society’s changing needs.

Looking ahead, the consortium’s enduring relevance will depend on its capacity to adapt while preserving its core ideals. If it continues to integrate technology thoughtfully, respect diversity, and prioritize meaningful feedback, it can serve as a guiding framework for future generations of assessment. Ultimately, the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium stands as both an instrument of measurement and a testament to education’s greater purpose: to nurture curiosity, foster critical thought, and empower every learner to reach their full potential in an ever-changing world.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I download my products after I have completed the purchase?

Your products are available immediately after you have made the payment. You can download them from your Member's Area. Right after your purchase has been confirmed, the website will transfer you to Member's Area. All you will have to do is login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long will my product be valid?

All Testking products are valid for 90 days from the date of purchase. These 90 days also cover updates that may come in during this time. This includes new questions, updates and changes by our editing team and more. These updates will be automatically downloaded to computer to make sure that you get the most updated version of your exam preparation materials.

How can I renew my products after the expiry date? Or do I need to purchase it again?

When your product expires after the 90 days, you don't need to purchase it again. Instead, you should head to your Member's Area, where there is an option of renewing your products with a 30% discount.

Please keep in mind that you need to renew your product to continue using it after the expiry date.

How often do you update the questions?

Testking strives to provide you with the latest questions in every exam pool. Therefore, updates in our exams/questions will depend on the changes provided by original vendors. We update our products as soon as we know of the change introduced, and have it confirmed by our team of experts.

How many computers I can download Testking software on?

You can download your Testking products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers/devices. To use the software on more than 2 machines, you need to purchase an additional subscription which can be easily done on the website. Please email support@testking.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our testing engine is supported by all modern Windows editions, Android and iPhone/iPad versions. Mac and IOS versions of the software are now being developed. Please stay tuned for updates if you're interested in Mac and IOS versions of Testking software.