Certification: Certified Fraud Examiner - Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

Certification Full Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

Certification Provider: ACFE

Exam Code: CFE - Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

Exam Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

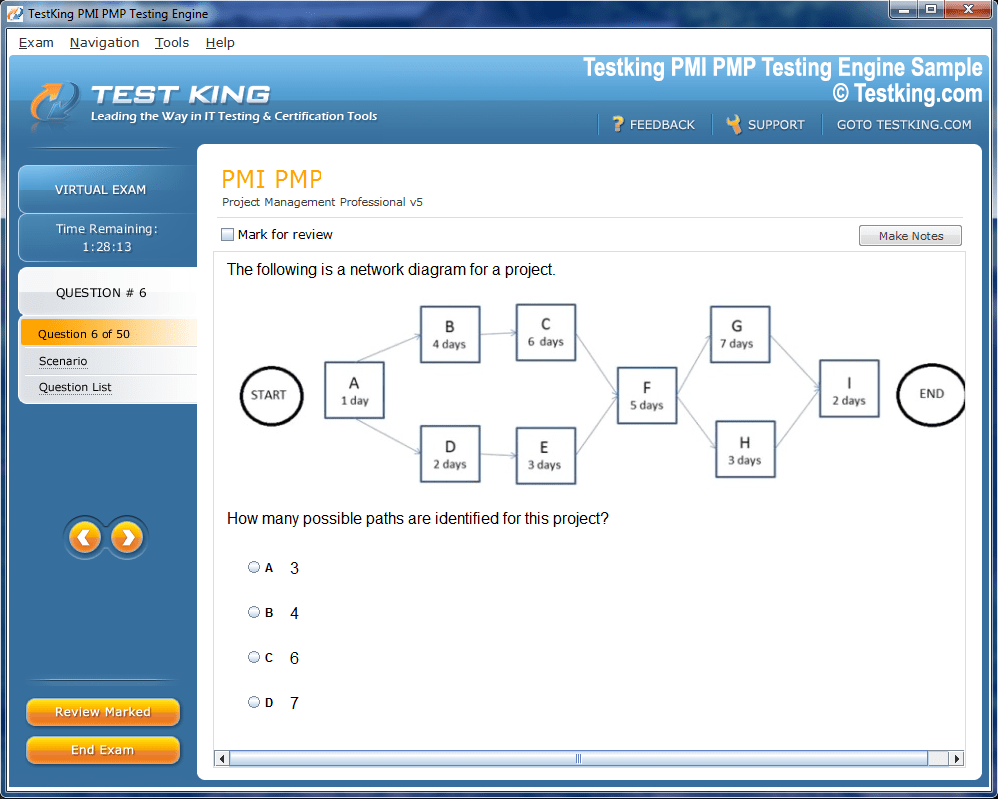

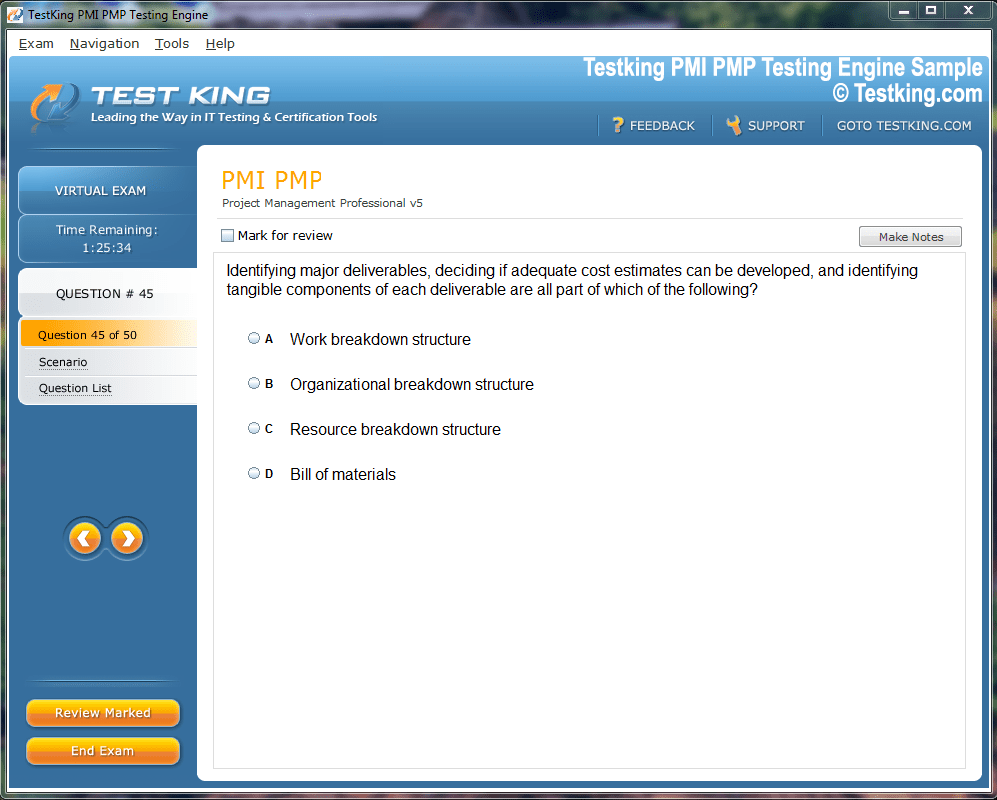

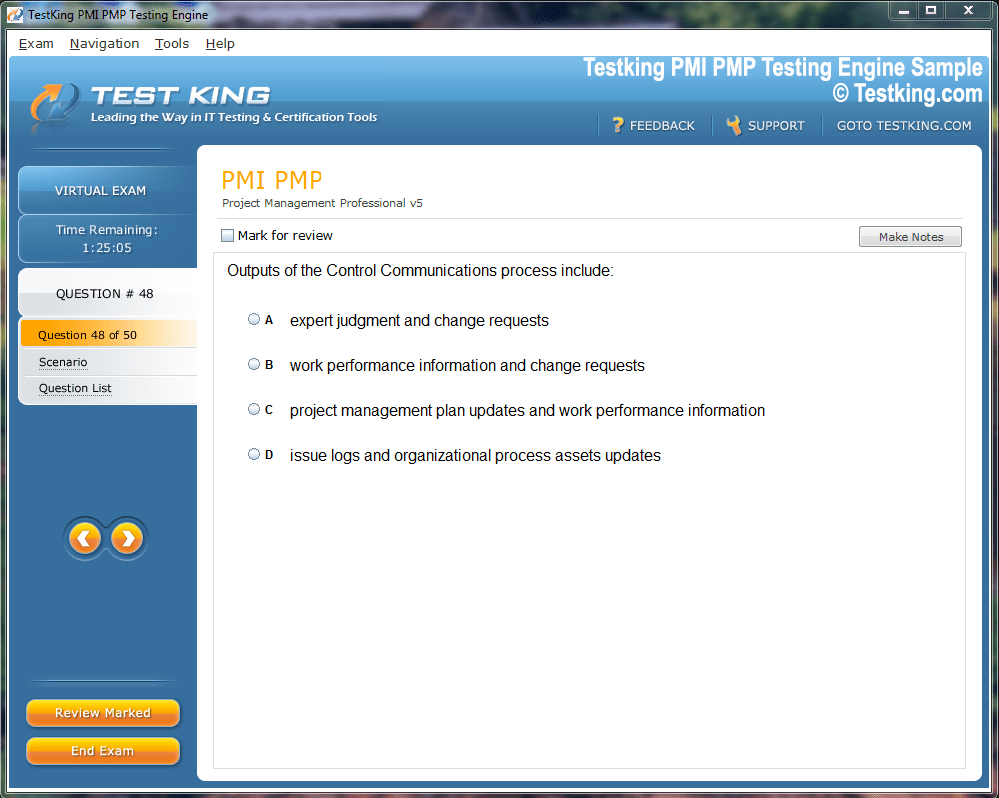

Product Screenshots

nop-1e =1

Mastering the CFE Exam: Foundations of Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

The Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) credential denotes proven expertise in fraud prevention, detection, and deterrence. CFEs are trained to identify the warning signs and red flags that indicate evidence of fraud and fraud risk. Earning this certification is a significant step for professionals in accounting, auditing, and law enforcement. The CFE Exam is a rigorous test of knowledge across four key sections: Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes, Law, Investigation, and Fraud Prevention and Deterrence. This series will focus specifically on the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section, which is often considered the most challenging part of the entire exam.

This section of the CFE Exam requires a deep understanding of accounting principles and the myriad ways they can be manipulated. Candidates must not only know how financial transactions are supposed to be recorded but also how they can be falsified to conceal illicit activity. It tests the ability to trace fraudulent transactions through complex accounting records and understand the schemes used by perpetrators. Success in this part of the exam is fundamental to the work of a fraud examiner, as financial records are the primary source of evidence in most fraud cases. This article will lay the foundational knowledge needed for this critical exam.

The Core of the CFE Exam: Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the CFE Exam is the bedrock upon which the other sections are built. It provides the technical knowledge necessary to understand and investigate the financial evidence of a crime. Without a firm grasp of accounting and auditing concepts, an investigator cannot effectively follow the money trail or identify anomalies in financial statements. This part of the exam covers a wide range of topics, from basic accounting theory to complex fraud schemes that can bring down entire corporations. It is designed to ensure that a certified professional can speak the language of finance fluently.

Preparing for this section of the exam demands a structured approach. It is not enough to simply memorize definitions of different fraud schemes. A candidate must understand the mechanics of each scheme, the internal control weaknesses that allow them to occur, and the audit tests or analytical procedures used to detect them. The exam questions are often scenario-based, requiring the application of knowledge to a practical situation. This section truly separates those who have a theoretical understanding from those who can apply that knowledge in a real-world investigative context, which is the ultimate goal of the CFE Exam.

Defining Fraud within the Exam Context

For the purposes of the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam, fraud is defined as any intentional act or omission designed to deceive others, resulting in the victim suffering a loss and the perpetrator achieving a gain. This definition is crucial because it distinguishes fraud from simple error. An unintentional mistake in the accounting records is an error; a deliberate misstatement to hide theft is fraud. The element of intent, or 'scienter', is a key component that a fraud examiner must often help establish. The exam will test your ability to recognize indicators of intent within a set of financial data.

The scope of fraud covered in the exam is vast. It encompasses everything from an employee stealing a few dollars from the cash register to a multi-billion dollar financial statement fraud scheme orchestrated by senior management. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) provides a framework for categorizing these schemes, known as the Fraud Tree. Understanding this classification system is essential for organizing your study efforts and for recognizing the patterns of different types of fraud. Each branch of the tree represents a different category of occupational fraud, which will be explored in this series.

The Fraud Triangle: A Universal Framework

A cornerstone of fraud theory, and a recurring concept in the CFE Exam, is the Fraud Triangle. Developed by criminologist Donald R. Cressey, this model posits that three factors are present in every situation of occupational fraud: perceived pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalization. Pressure refers to a motivator in the perpetrator's life, such as a financial hardship, a gambling addiction, or an intense workplace performance goal. This is the 'why' behind the fraudulent act. The exam will expect you to identify potential pressures when analyzing a case study.

Opportunity is the condition or situation that allows the fraud to occur. This is typically created by weak internal controls, a lack of oversight, or the abuse of a position of trust. A fraud examiner's primary role in prevention is to help organizations reduce opportunity. Rationalization is the personal justification the fraudster uses to make their actions seem acceptable to themselves. Common rationalizations include "I was only borrowing the money," "the company owes it to me," or "it's for a good purpose." Understanding these three elements helps an examiner not only detect fraud but also understand its root causes.

Navigating the ACFE Fraud Tree

The ACFE Fraud Tree is a classification model that is indispensable for studying for the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the exam. It divides occupational fraud into three primary categories: Asset Misappropriation, Corruption, and Financial Statement Fraud. Each of these main branches then splits into more specific sub-categories and individual scheme types. This structured model provides a clear roadmap for the vast landscape of fraudulent conduct you will be tested on. The exam will require you to identify, differentiate, and understand the mechanics of schemes from all parts of the tree.

Asset Misappropriation is the most common category of occupational fraud, although it often has the lowest median loss. It involves an employee stealing or misusing the employing organization's resources. This category includes cash schemes like skimming and larceny, as well as the theft of non-cash assets like inventory. Corruption schemes involve an employee wrongfully using their influence in a business transaction to procure some benefit for themselves or another person, contrary to their duty to their employer. Examples include bribery and conflicts of interest. Financial Statement Fraud involves the intentional misstatement or omission of material information from financial reports.

Fundamental Accounting Concepts for the Exam

A solid understanding of basic accounting and bookkeeping is non-negotiable for passing this part of the CFE Exam. You must be comfortable with the double-entry accounting system, where every transaction has an equal and opposite effect in at least two different accounts. This means understanding debits and credits, the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity), and how transactions flow from source documents to journals and ledgers, and ultimately into the financial statements. The exam will assume you have this baseline knowledge.

You will need to be familiar with the key financial statements: the Balance Sheet, the Income Statement, the Statement of Cash Flows, and the Statement of Owners' Equity. For the exam, you must know what each statement represents and how they are interconnected. For example, Net Income from the Income Statement flows into the Statement of Owners' Equity, and the ending equity balance is reported on the Balance Sheet. Fraud schemes often create inconsistencies between these statements, and your ability to spot those inconsistencies is a critical exam skill.

The Role of Internal Controls

Internal controls are the policies, procedures, and systems that an organization implements to safeguard assets, ensure the accuracy of financial records, promote operational efficiency, and encourage adherence to management policies. A significant portion of the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes exam focuses on how weak internal controls create opportunities for fraud. You must be able to identify control weaknesses in a given scenario and explain how they could be exploited. This is a central theme throughout the CFE Exam material.

Key internal control concepts you must master include segregation of duties, which involves separating the functions of authorization, record-keeping, and asset custody. Other important controls are physical safeguards over assets, independent checks and reconciliations, and proper authorization of transactions. The exam will test your ability to recognize both preventative controls, which are designed to stop fraud from happening in the first place, and detective controls, which are designed to identify fraud after it has occurred. Understanding this framework is vital for answering many exam questions correctly.

An Introduction to Asset Misappropriation Schemes

Asset misappropriation schemes are by far the most common form of occupational fraud, though they typically involve smaller financial losses than financial statement fraud. This category is broadly divided into cash schemes and non-cash schemes. The CFE Exam requires a detailed understanding of the various methods perpetrators use to steal these assets. Cash is the most frequently targeted asset because it is liquid and easily transportable. The exam material delves deeply into the specifics of how cash is stolen.

Cash schemes are further broken down into three main types: larceny, skimming, and fraudulent disbursements. Cash larceny involves stealing cash that has already been recorded in the victim company's books. Skimming is the theft of cash before it has been recorded, making it an "off-book" fraud that is more difficult to detect. Fraudulent disbursements are schemes where an employee causes the organization to make a payment for a fraudulent purpose. This is the most common and costly type of cash misappropriation and includes billing schemes, payroll schemes, and check tampering.

A Primer on Corruption for the CFE Exam

Corruption schemes represent a significant threat to organizations and are a key area of study for the CFE Exam. In these schemes, fraudsters use their influence in business transactions to gain a direct or indirect benefit. These acts are often hidden and can be difficult to detect without a tip or a proactive investigation. The exam will test your knowledge of the four sub-categories of corruption: bribery, illegal gratuities, economic extortion, and conflicts of interest. Each has distinct elements that you must be able to differentiate.

Bribery involves offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting anything of value to influence an official act or a business decision. Illegal gratuities are similar, but they are given after a decision has been made as a reward, rather than to influence it beforehand. Economic extortion is the opposite of bribery; it involves an employee demanding a payment from a vendor or customer in order to make a particular business decision. Finally, a conflict of interest occurs when an employee has an undisclosed personal economic interest in a transaction that could adversely affect the company.

Initial Look at Financial Statement Fraud

While it is the least common of the three primary categories of occupational fraud, financial statement fraud is by far the most costly on a per-incident basis. These schemes are typically perpetrated by senior management who have the authority to override internal controls and manipulate accounting records. The motivation is often to deceive investors, creditors, or regulatory bodies about the true financial health of the organization. The CFE Exam will test your ability to understand the methods used to falsify financial statements and the analytical techniques used to detect them.

The most common types of financial statement fraud involve the overstatement of assets and revenues or the understatement of liabilities and expenses. Common schemes include recording fictitious revenues, improperly timing revenue recognition, concealing liabilities, and improperly valuing assets. Detecting these schemes requires a different skillset than investigating asset misappropriation. It relies heavily on financial statement analysis, including vertical and horizontal analysis and ratio analysis, to identify anomalies that may indicate manipulation. These techniques are a critical component of the material you must master for the exam.

CFE Exam Deep Dive: Asset Misappropriation - Cash Schemes

Cash is the lifeblood of any organization, and its liquidity and universal acceptance make it the most frequently targeted asset in fraud schemes. The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam places a heavy emphasis on understanding the multitude of ways cash can be misappropriated. For the exam, it is not enough to know that cash was stolen; you must be able to identify the specific methodology used by the fraudster. The ACFE framework divides cash misappropriation into three primary groups: cash larceny, skimming, and fraudulent disbursements.

Each of these categories has unique characteristics, occurs at a different point in the accounting cycle, and requires different methods of concealment. Cash larceny, for instance, is the theft of on-book cash, meaning it creates an imbalance in the accounts that must be hidden. Skimming is the theft of off-book cash, which presents a different set of challenges for detection. Fraudulent disbursements involve tricking the company into making what appears to be a legitimate payment. Mastering the distinctions between these schemes is absolutely essential for success on the CFE Exam.

CFE Exam Focus: Non-Cash Asset Misappropriation and Concealment

While cash is the most frequently stolen asset, the misappropriation of non-cash tangible and intangible assets presents a significant risk to organizations and is a key topic on the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam. Non-cash assets can include everything from inventory and supplies to company equipment and intellectual property. The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the exam requires a thorough understanding of how these assets are stolen, misused, and how the theft is concealed. These schemes can be just as damaging as cash fraud, and in some cases, even more so.

The theft of non-cash assets is typically more difficult to convert to cash, which often makes these schemes less appealing to fraudsters than direct cash theft. However, for employees in certain positions, such as warehouse staff or IT administrators, access to non-cash assets may be easier than access to cash. The CFE Exam will test your knowledge of the various types of non-cash schemes, the internal control weaknesses that permit them, and the investigative techniques used to uncover them. This includes a deep dive into inventory fraud, misuse of assets, and the theft of proprietary information.

Inventory and Other Assets: Misuse Schemes

One of the primary categories of non-cash fraud is the simple misuse of company assets. This can range from an employee using a company vehicle for a personal vacation to using company computers and servers for a side business. While some may view this as a minor infraction, it can result in significant costs to the organization through increased wear and tear, fuel consumption, and other direct expenses. The CFE Exam requires you to differentiate between simple misuse and outright theft. Misuse typically involves borrowing or using an asset temporarily, not permanently depriving the organization of it.

These schemes are often difficult to detect as they may not immediately impact the financial statements in a material way. They are usually discovered through observation, employee tips, or through analytical review that reveals unusually high operating costs in a particular department. For example, an unusually high fuel expense for a specific company vehicle might indicate unauthorized personal use. The exam will expect you to recognize that while less financially dramatic, these schemes are still a form of occupational fraud that must be addressed through clear policies and effective oversight.

Detection of Non-Cash Misappropriation

Detecting the theft of non-cash assets requires a combination of analytical review, physical observation, and robust internal controls. The CFE Exam will test your knowledge of these detection methods. For inventory, analytical procedures can be very effective. An examiner might calculate inventory turnover ratios or analyze trends in shrinkage, scrap, and write-offs. An unexplained deviation from historical norms could indicate fraud. A sudden increase in the cost of goods sold as a percentage of sales can also be a significant red flag.

Physical inventory counts are a fundamental detective control. However, a fraudster may try to conceal theft during a count by, for example, stacking empty boxes to look like full ones or including obsolete items in the count. Therefore, auditors and examiners must be diligent during the observation of a physical count. For other non-cash assets, maintaining a detailed fixed asset register and conducting periodic inventories of equipment is crucial. Ultimately, one of the most effective sources for detecting non-cash theft is through employee tips, highlighting the importance of a well-publicized whistleblower hotline.

Prevention of Non-Cash Asset Theft

Preventing the theft of non-cash assets, like all fraud prevention, relies on strong internal controls. The CFE Exam emphasizes the importance of a proactive approach. The first line of defense is proper separation of duties. The person responsible for ordering inventory should not also be able to receive it or approve payment for it. Similarly, the person who maintains the fixed asset register should not have custody of those assets. This segregation of duties makes it much more difficult for a single individual to commit and conceal fraud.

Other critical preventative controls include physical security measures, such as locks, fences, and security cameras for warehouses and storage areas. Access controls are also vital, both for physical locations and for company data systems. Not all employees need access to sensitive areas or information. Finally, the CFE Exam materials stress the importance of clear policies regarding the personal use of company assets and a strong ethical tone set by management. When employees know that theft is taken seriously and that controls are in place, they are less likely to see an opportunity to commit fraud.

Linking Non-Cash Schemes to Financial Records

A key skill tested on the CFE Exam is the ability to connect the physical act of theft to its impact on the financial statements. The theft of non-cash assets, especially inventory, directly affects the balance sheet and the income statement. When inventory is stolen, the inventory asset account on the balance sheet is overstated until the theft is discovered and written off. This overstatement can mislead investors and creditors about the company's true financial position.

Simultaneously, the income statement is affected. If the theft is concealed by debiting cost of goods sold, then profits will be understated. If the asset is simply removed without any accounting entry, the cost of goods sold will be understated, and profits will be overstated until a physical count reveals the shortage. This can lead to the payment of excess income taxes on illusory profits. Understanding this dual impact and being able to trace the fraudulent entries through the accounting system is a high-level skill required for the CFE Exam.

CFE Exam Analysis: Deconstructing Financial Statement Fraud Schemes

Financial statement fraud is the deliberate misrepresentation of the financial condition of an enterprise accomplished through the intentional misstatement or omission of amounts or disclosures in the financial statements to deceive financial statement users. While it is the least common form of occupational fraud covered on the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam, it is by far the most costly. These schemes are typically perpetrated by upper-level management who have the authority to override internal controls. The motivation is often to boost stock prices, secure financing, or achieve personal performance bonuses.

The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the CFE Exam requires a distinct set of skills to master this topic. Unlike asset misappropriation, which involves stealing from the company, financial statement fraud is often committed for the company, at least in the short term. The exam will test your ability to understand the various methods used to manipulate earnings and to apply analytical techniques to detect the warning signs of this manipulation. This is a critical area for any professional who relies on the integrity of financial reporting.

Methods of Committing Financial Statement Fraud

The CFE Exam classifies financial statement fraud into five broad categories. These are: fictitious revenues, timing differences, concealed liabilities and expenses, improper asset valuations, and improper disclosures. It is crucial for exam candidates to understand the mechanics and red flags associated with each of these methods. Perpetrators often use a combination of these techniques to create a distorted picture of the company's performance and financial health. The exam will present scenarios where you must identify which type of scheme is being used based on the evidence provided.

Fictitious revenues involve creating fake sales, while timing differences involve booking revenues or expenses in the wrong period to smooth earnings or meet targets. Concealed liabilities are schemes to hide debts and obligations, making the company appear less leveraged than it truly is. Improper asset valuations involve inflating the value of assets like inventory, accounts receivable, or fixed assets. Finally, improper disclosures involve omitting or misrepresenting important information in the footnotes to the financial statements.

Fictitious and Inflated Revenues

Recording fictitious revenues is a straightforward but powerful way to manipulate financial results. This can be done by creating fake invoices for non-existent customers, or by colluding with a legitimate customer to record a sale that never actually took place. The CFE Exam will expect you to know how these schemes impact the accounting equation. A fictitious sale increases both revenues and accounts receivable. Since the receivable is fake and will never be collected, it can be a major red flag for this type of fraud.

A related scheme is recording inflated revenues. This might involve intentionally shipping the wrong or defective goods to a customer and booking the full sale, knowing the items will likely be returned in a subsequent period. This practice improperly accelerates revenue recognition. The exam will test your knowledge of detection techniques, such as analyzing the relationship between sales and accounts receivable. A significant increase in the "days sales in receivable" ratio can indicate that a company is booking sales faster than it is collecting cash, a classic sign of fictitious or premature revenue.

Timing Differences: Premature Revenue Recognition

Timing difference schemes involve recognizing revenues or expenses in the wrong accounting period. The most common form is premature revenue recognition, which is the practice of booking revenue before it has been earned under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). For a sale to be properly recognized, the earnings process must be complete, and collectability must be reasonably assured. The CFE Exam will require you to understand these criteria and how they can be subverted.

One classic example is a "bill and hold" sale, where a company bills a customer for goods but does not ship them, holding them in its own warehouse. Unless specific, strict criteria are met, this does not qualify for revenue recognition. Another technique is to keep the books open past the end of an accounting period to record sales from the next period. Detecting these schemes often involves reviewing sales contracts for specific terms, examining shipping documents to confirm delivery dates, and analyzing sales trends for unusual spikes at the end of a quarter or year.

Concealed Liabilities and Expenses

To make a company appear more profitable and financially stable, management might engage in schemes to conceal liabilities and expenses. This has the effect of artificially inflating net income and equity. The CFE Exam covers several methods for doing this. One common technique is liability/expense omission. This is simply the failure to record a liability and its corresponding expense when it has been incurred. For example, a company might fail to record utility expenses for the last month of the year.

Another method is capitalized expenses. This involves improperly capitalizing costs that should have been expensed, such as routine maintenance or marketing costs. By capitalizing these costs, they are moved from the income statement (as an expense) to the balance sheet (as an asset), thereby increasing current period profits. A third method is the failure to disclose contingent liabilities, such as pending lawsuits or loan guarantees, in the footnotes of the financial statements. The exam will test your ability to spot these omissions and misclassifications.

Improper Asset Valuations

Inflating the value of assets on the balance sheet is another common financial statement fraud scheme. Overstating assets makes the company appear to have a stronger financial position and can be used to meet loan covenants. The CFE Exam will test your knowledge of how various assets can be improperly valued. Inventory valuation is a prime area for manipulation. This can be done by misrepresenting the quantity of inventory on hand, or by assigning it a value that is higher than its actual cost or market value, for instance, by failing to write down obsolete inventory.

Accounts receivable can also be overstated by failing to write off accounts that are known to be uncollectible. This keeps fictitious or non-collectible receivables on the books as assets. Fixed assets can be inflated by leaving worthless or disposed-of assets on the books or by improperly capitalizing costs associated with those assets. The exam will require you to understand the accounting rules for asset valuation and the audit procedures used to verify these balances, such as observing physical inventory and confirming accounts receivable with customers.

Improper Disclosures

Financial statement fraud is not just about the numbers on the face of the statements; it can also involve improper disclosures in the footnotes. The footnotes provide crucial context and additional detail that is essential for a complete understanding of the company's financial health. The CFE Exam recognizes that omitting or misrepresenting information in the disclosures can be just as deceptive as manipulating the primary financial statements. This is a qualitative, rather than quantitative, form of fraud.

Examples of improper disclosures include the failure to disclose significant related-party transactions, which could reveal conflicts of interest. It could also involve failing to disclose material subsequent events that occur after the balance sheet date but before the financial statements are issued. Omitting details about contingent liabilities, changes in accounting policies, or significant risks and uncertainties can all mislead investors. The exam will test your understanding of what constitutes a material disclosure and the potential impact of its omission.

Financial Statement Analysis for Fraud Detection

Detecting financial statement fraud relies heavily on analytical techniques. The CFE Exam will test your ability to use these tools to spot red flags. Vertical analysis involves stating each line item on a financial statement as a percentage of a base amount (e.g., sales on the income statement or total assets on the balance sheet). This allows for the comparison of a company's structure over time and against industry benchmarks. A sudden, unexplained change in a key percentage can be a warning sign.

Horizontal analysis, or trend analysis, involves comparing account balances over several periods to identify unusual changes. For example, if revenues have grown by 10% but accounts receivable have grown by 50%, it could indicate that the company is booking sales that are not being collected. Ratio analysis is another powerful tool. Ratios like the current ratio, debt-to-equity ratio, and inventory turnover can provide insights into a company's liquidity, solvency, and operational efficiency. The exam will expect you to know these key ratios and what they signify.

The Role of Corporate Governance and the Audit Committee

Strong corporate governance is a key defense against financial statement fraud. The CFE Exam materials emphasize the role of the board of directors and, specifically, the audit committee in overseeing the financial reporting process. An independent and financially literate audit committee is responsible for hiring and overseeing the external auditors, reviewing the internal controls over financial reporting, and ensuring the integrity of the financial statements. A weak or passive audit committee is a major red flag for fraud risk.

The exam will test your understanding of the characteristics of an effective audit committee. This includes independence from management, financial expertise among its members, and regular meetings with both internal and external auditors without management present. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, passed in response to major accounting scandals, established many of the modern requirements for audit committees of public companies. A basic understanding of this regulatory environment is essential for the CFE Exam.

Nonfinancial Performance Measures

Sometimes, the first sign of financial statement fraud is not in the financial numbers themselves, but in the disconnect between the company's reported financial performance and its nonfinancial performance. The CFE Exam may present scenarios where you need to look beyond the financial statements. For example, a company might report a massive increase in revenue, but the data on its factory output, shipping volumes, or employee headcount does not show a corresponding increase. This suggests the reported revenue growth may not be real.

Other nonfinancial red flags can include a high rate of turnover in senior management or the chief financial officer position, the use of an audit firm that is not well-known or respected, or overly complex organizational structures that seem designed to obscure the true nature of transactions. An effective fraud examiner learns to look at the big picture and question situations where the financial story does not align with the operational reality. The exam will test this type of critical thinking.

CFE Exam Synthesis: Corruption, Other Frauds, and Final Preparation

Corruption schemes represent a significant departure from asset misappropriation and financial statement fraud, and they form the third major branch of the ACFE Fraud Tree. These schemes are characterized by an employee misusing their influence in a business transaction to gain a direct or indirect benefit. This area of the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam tests your ability to identify the various forms of corrupt acts, understand the legal and ethical implications, and recognize the environments where corruption is most likely to thrive. It often involves collusion between an employee and an outside party.

Unlike other fraud types that may leave a clear accounting trail, corruption schemes are often hidden within seemingly legitimate transactions. The evidence is more likely to be found in emails, contracts, and lifestyle changes of the perpetrator rather than in the general ledger. The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes exam requires you to understand the four subcategories of corruption: bribery, illegal gratuities, economic extortion, and conflicts of interest. Mastering the distinctions between these is crucial for the exam.

Bribery and Illegal Gratuities

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of anything of value to influence an official act or a business decision. The key element is the intent to influence a decision before it is made. For example, a vendor might pay a purchasing manager to ensure their company is awarded a contract. The CFE Exam will test your ability to recognize scenarios involving kickbacks, which are a form of bribery where a vendor submits an inflated invoice and "kicks back" a portion of the overpayment to the corrupt employee.

Illegal gratuities are similar to bribery but with a crucial difference in timing and intent. An illegal gratuity is something of value given to an employee to reward a decision after it has been made, rather than to influence it beforehand. For example, a vendor who was awarded a contract might give the purchasing manager an expensive gift as a "thank you." While there is no evidence of a prior agreement to influence the decision, it is still considered a corrupt act because it can create an expectation of future favorable treatment. The exam will require you to differentiate between these two concepts.

Economic Extortion and Conflicts of Interest

Economic extortion is the "opposite" of bribery. Instead of a vendor offering a payment to an employee, economic extortion occurs when an employee demands a payment from a vendor in order to make a favorable business decision. For instance, a government inspector might demand payment from a restaurant owner to grant a health and safety permit. The employee is using the threat of adverse action (e.g., failing the inspection) to extort money. This is essentially a "pay me or else" scenario.

A conflict of interest arises when an employee, manager, or executive has an undisclosed personal or economic interest in a transaction that could adversely affect the organization. The CFE Exam covers common conflict schemes like purchasing schemes, where a manager approves purchases from a company they secretly own, or sales schemes, where a manager sells goods at a discount to a company in which they have a hidden interest. The core issue is the undisclosed conflict; the fraud is in the failure to disclose the personal interest.

Detecting and Preventing Corruption

Detecting corruption is notoriously difficult because it often lacks a clear financial trail and involves collusion. The CFE Exam emphasizes that tips and complaints are the most common way corruption is uncovered. Therefore, having a robust and well-publicized whistleblower program is a critical preventive and detective control. Analytically, red flags can include a vendor's prices being consistently higher than competitors, a single vendor receiving an unusually large volume of contracts, or an employee's lifestyle appearing to exceed their known salary.

Prevention of corruption relies on a strong ethical tone at the top, clear policies regarding gifts and conflicts of interest, and regular training for employees on what constitutes corrupt behavior. For the exam, you should know that requiring employees to sign an annual conflict of interest disclosure statement is a key preventative control. Conducting proper due diligence on new vendors can also help identify potential red flags, such as a vendor's address matching an employee's home address.

Consumer and Other Miscellaneous Fraud Schemes

While the CFE Exam focuses heavily on occupational fraud, it also covers other types of fraud that an examiner may encounter. This includes various consumer fraud schemes. You should have a general understanding of identity theft, where a fraudster uses another person's identifying information to commit fraud, and advance-fee scams, where a victim is persuaded to pay a small upfront fee in the promise of a much larger gain that never materializes. Phishing and other social engineering schemes used to obtain sensitive information are also relevant.

The exam may also touch upon computer and internet fraud. This includes everything from hacking and unauthorized access to company systems to manipulate data, to using computer systems to perpetrate other fraud schemes like billing or payroll fraud. While a deep technical knowledge is not required for the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section, you should understand how technology can be used to facilitate and conceal fraud, and the types of digital evidence that might be created.

Synthesizing Knowledge for the Exam

Passing the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the CFE Exam requires more than just memorizing individual fraud schemes. It requires the ability to synthesize information from across the curriculum. A single scenario presented on the exam might involve elements of asset misappropriation, financial statement fraud, and corruption. You must be able to see the complete picture, identify the different types of fraud being committed, and understand how they might be interrelated.

For example, a manager might be creating fictitious sales (financial statement fraud) to a shell company they own (conflict of interest) and using those transactions to embezzle funds from the company (asset misappropriation). Your preparation should include practicing with case studies and scenario-based questions that force you to connect these different concepts. The goal of the exam is to test your ability to think like a real fraud examiner who must analyze complex and often messy situations.

Conclusion

As you finalize your preparation for this section of the CFE Exam, focus on active learning rather than passive reading. Use flashcards to test your knowledge of key terms and the elements of different schemes. Work through as many practice questions as you can. The official ACFE CFE Exam Prep Course is an invaluable resource that provides questions formatted like the actual exam. Pay close attention to the explanations for the answers you get wrong; this is where the most effective learning happens.

Create summary sheets or mind maps to organize the vast amount of information. For example, create a chart that lists each fraud scheme, its definition, the concealment methods used, and the primary detection techniques. This will help you see the patterns and relationships between different concepts. Practice your financial statement analysis skills. Be comfortable calculating and interpreting key financial ratios, as these are likely to appear on the exam.

On the day of the exam, it is important to manage your time effectively. The CFE Exam is computer-based, and each section has a time limit. Read each question carefully. Many questions are presented as short scenarios. Identify the key facts and what the question is specifically asking. Eliminate obviously incorrect answers first to narrow down your choices. Do not get stuck on a single difficult question; it is better to make an educated guess and move on to ensure you have time to answer all the questions.

Trust in your preparation. The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section is comprehensive, but by following a structured study plan, you will have covered all the necessary material. The exam is designed to test your ability to apply your knowledge, so think critically about each scenario. Remember the core principles like the Fraud Triangle, the importance of internal controls, and the different branches of the Fraud Tree. These foundational concepts will provide a framework for analyzing even the most complex questions you encounter on the exam.

Completing the Certified Fraud Examiner Exam is a challenging but rewarding process. The knowledge gained while studying for the Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section is directly applicable to the daily work of any anti-fraud professional. This section provides the technical core of the CFE skillset, enabling you to understand the "how" and "why" of financial crimes. It empowers you to dissect complex financial data, identify the red flags of fraud, and follow the money trail to uncover the truth.

Earning the CFE credential demonstrates a commitment to the profession and a high level of expertise. It opens doors to new career opportunities and establishes you as a leader in the anti-fraud community. This five-part series has provided a roadmap for tackling one of the most demanding sections of the exam. With diligent study and a firm grasp of these core concepts, you will be well-equipped to pass the exam and take a significant step forward in your professional journey.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I download my products after I have completed the purchase?

Your products are available immediately after you have made the payment. You can download them from your Member's Area. Right after your purchase has been confirmed, the website will transfer you to Member's Area. All you will have to do is login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long will my product be valid?

All Testking products are valid for 90 days from the date of purchase. These 90 days also cover updates that may come in during this time. This includes new questions, updates and changes by our editing team and more. These updates will be automatically downloaded to computer to make sure that you get the most updated version of your exam preparation materials.

How can I renew my products after the expiry date? Or do I need to purchase it again?

When your product expires after the 90 days, you don't need to purchase it again. Instead, you should head to your Member's Area, where there is an option of renewing your products with a 30% discount.

Please keep in mind that you need to renew your product to continue using it after the expiry date.

How often do you update the questions?

Testking strives to provide you with the latest questions in every exam pool. Therefore, updates in our exams/questions will depend on the changes provided by original vendors. We update our products as soon as we know of the change introduced, and have it confirmed by our team of experts.

How many computers I can download Testking software on?

You can download your Testking products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers/devices. To use the software on more than 2 machines, you need to purchase an additional subscription which can be easily done on the website. Please email support@testking.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our testing engine is supported by all modern Windows editions, Android and iPhone/iPad versions. Mac and IOS versions of the software are now being developed. Please stay tuned for updates if you're interested in Mac and IOS versions of Testking software.