Certification: Certified Fraud Examiner - Fraud Prevention

Certification Full Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Fraud Prevention

Certification Provider: ACFE

Exam Code: CFE - Fraud Prevention

Exam Name: Certified Fraud Examiner - Fraud Prevention

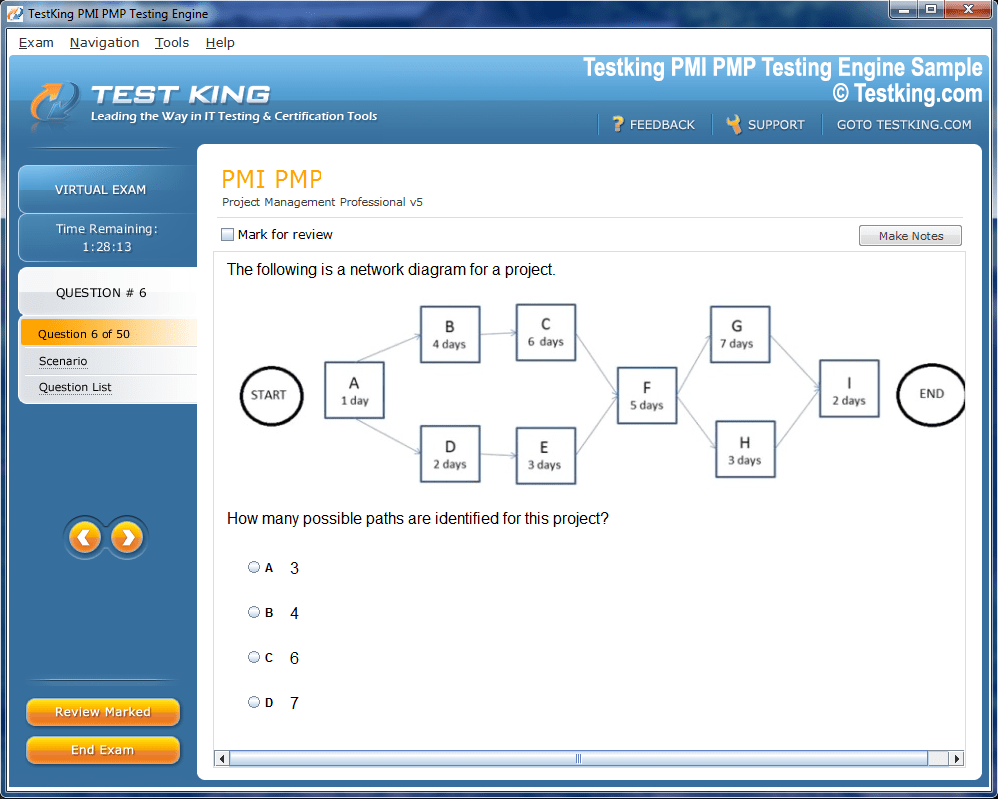

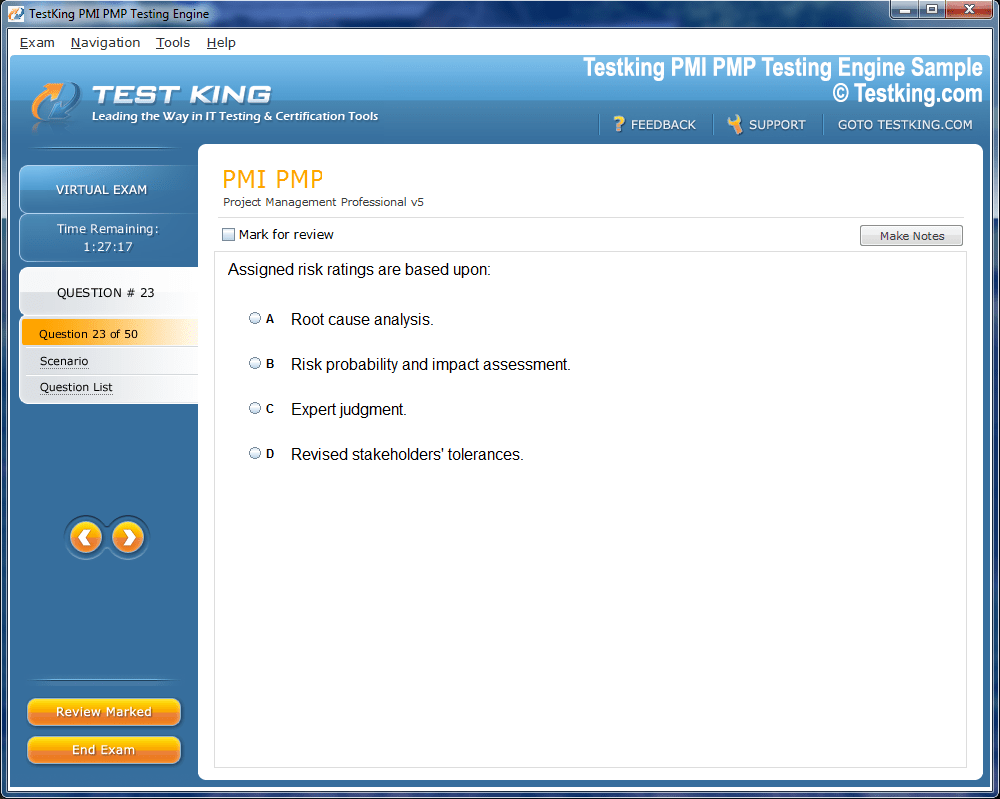

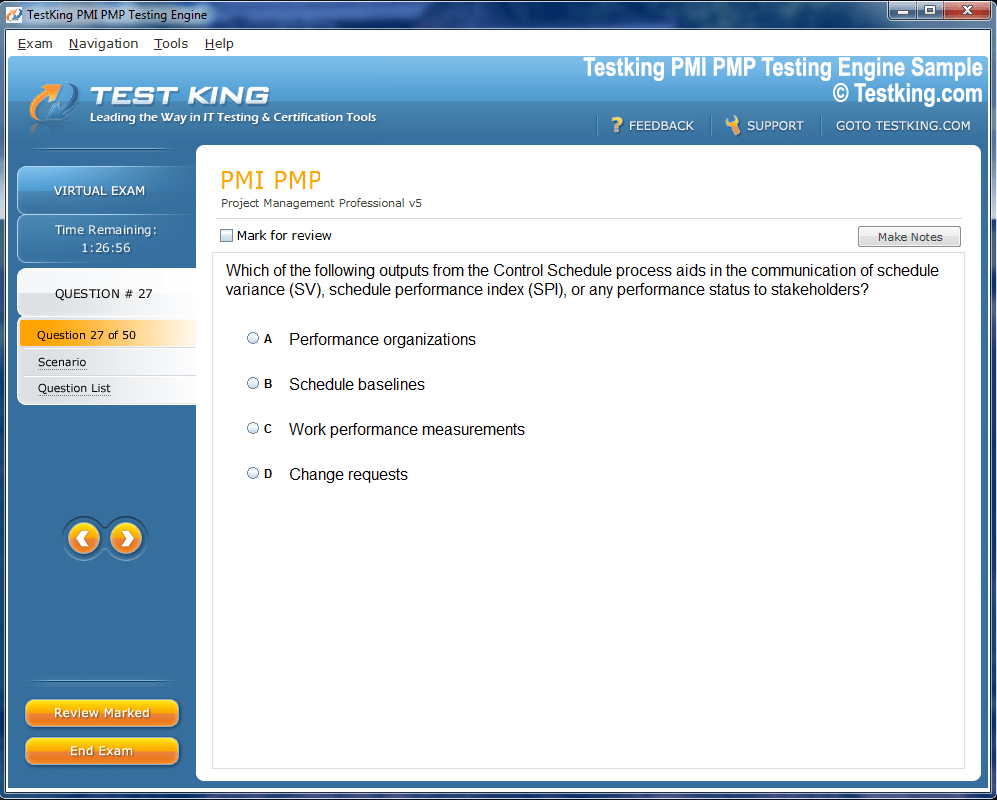

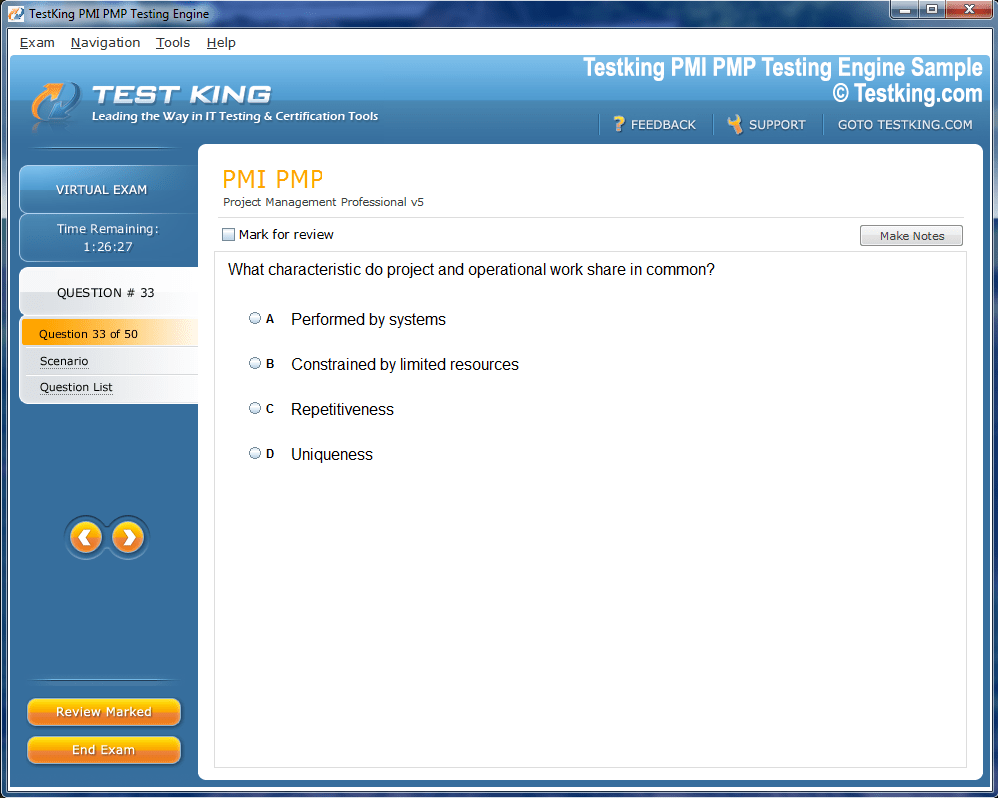

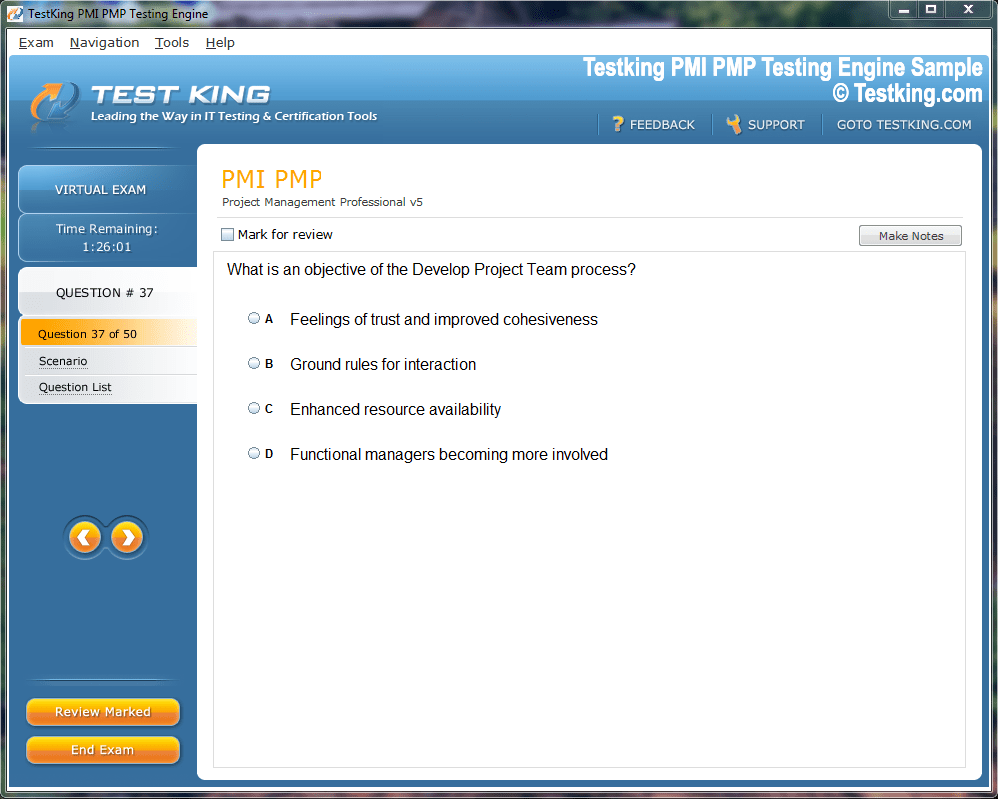

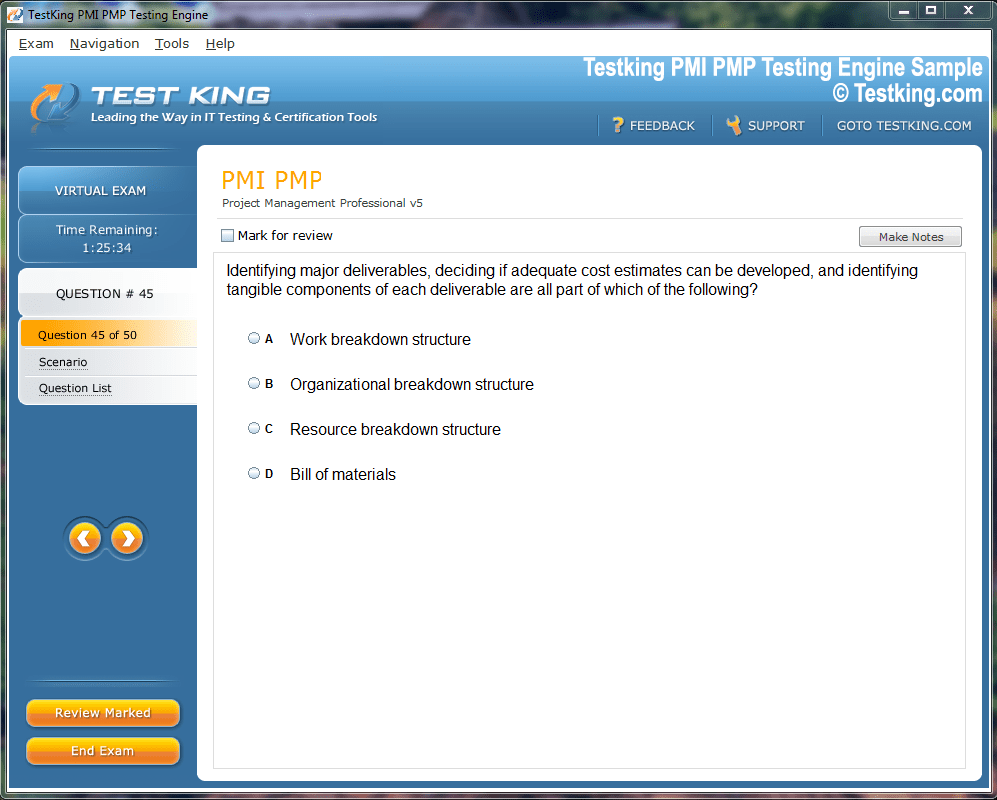

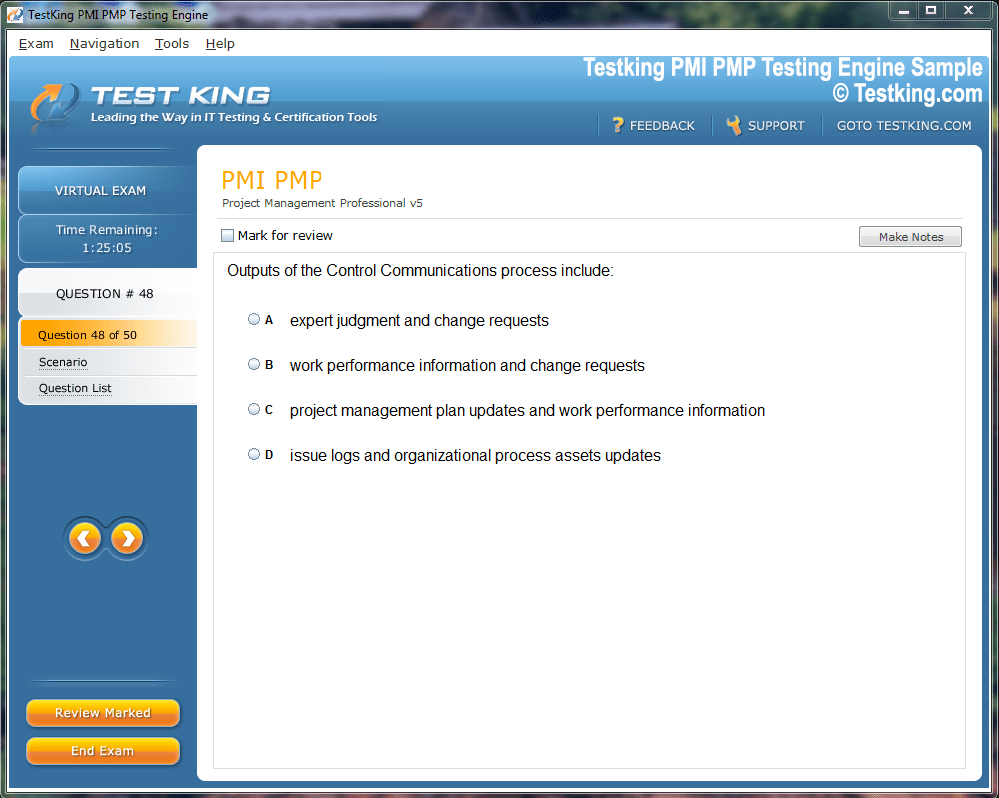

Product Screenshots

nop-1e =1

Unveiling the Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) Exam and the World of Fraud Prevention

The Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) credential represents the gold standard in the anti-fraud profession. It is a globally recognized certification awarded by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), the world’s largest anti-fraud organization. Achieving this designation signifies a proven expertise in preventing, detecting, and deterring fraud.

The CFE exam is designed to test a comprehensive body of knowledge that spans four critical areas of fraud examination. Professionals who hold the CFE credential are seen as specialists with a unique set of skills that are invaluable to organizations across all sectors, from publicly traded companies to government agencies and non-profits.

The Role of a Certified Fraud Examiner

A Certified Fraud Examiner is a trusted advisor who helps organizations protect their assets and reputation from the threat of fraud. Their responsibilities are multifaceted, often involving proactive measures to prevent fraud before it occurs and reactive measures to investigate it once suspected. CFEs are skilled in understanding how fraud is committed and how it can be identified. They may be involved in designing and implementing internal controls, conducting fraud risk assessments, investigating complex financial transactions, interviewing witnesses and suspects, and providing litigation support. Their work is crucial in minimizing financial losses and ensuring compliance with regulations.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE)

The ACFE is the professional body that sets the standards for the anti-fraud industry and administers the CFE exam. Founded in 1988, its mission is to reduce the incidence of fraud and white-collar crime through education, advocacy, and a global network of professionals. The ACFE provides its members with extensive resources, including training, research, and networking opportunities. It promotes a common body of knowledge for fraud examiners and upholds a strict Code of Professional Ethics that all CFEs must adhere to, ensuring integrity and objectivity in their work. The organization is the cornerstone of the profession.

Understanding the Fraud Triangle

A foundational concept in the study of fraud is the Fraud Triangle, developed by criminologist Donald R. Cressey. This model posits that three elements are typically present when an ordinary person commits fraud: perceived pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalization. Pressure often comes from a financial need that the individual feels cannot be shared, such as debt or an expensive lifestyle. Opportunity refers to the person's ability to commit the fraud, usually due to weak internal controls or a position of trust. Rationalization is the mental process by which the individual justifies their dishonest actions, for example, by thinking "I'm only borrowing the money."

The Four Pillars of the CFE Exam

The CFE exam is structured around four key disciplines that collectively cover the entire lifecycle of fraud. The first section is Fraud Prevention and Deterrence, which focuses on the proactive side of fraud risk management. The second is Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes, which requires candidates to understand the countless ways individuals can exploit accounting systems for personal gain. The third pillar is Investigation, which covers the techniques and procedures for gathering evidence and conducting inquiries. The final section, Law, ensures that examiners understand the legal ramifications of fraud and the rules governing investigations and evidence.

Focus on Fraud Prevention and Deterrence

The Fraud Prevention and Deterrence section of the CFE exam is crucial because it addresses the most cost-effective way to combat fraud: stopping it before it happens. This domain tests a candidate's knowledge of why people commit fraud and how to create systems and processes that reduce the opportunities for it. Topics include understanding criminal behavior, implementing fraud prevention programs, conducting fraud risk assessments, and promoting an ethical corporate culture. It is about shifting an organization's mindset from being reactive to being proactive in its fight against financial crime and passing the exam.

Creating an Anti-Fraud Culture

One of the most powerful fraud prevention tools is not a system or a policy, but a culture. A strong anti-fraud culture starts with a clear "tone at the top," where leadership demonstrates an unwavering commitment to integrity and ethical behavior. This message must then be embedded throughout the organization. This is achieved through a formal code of conduct, regular ethics training, and holding all employees, regardless of their position, accountable for their actions. When employees see that honesty is valued and misconduct is not tolerated, they are far less likely to rationalize fraudulent behavior.

Internal Controls: The First Line of Defense

Internal controls are the specific policies, procedures, and activities put in place to protect an organization’s assets and ensure the integrity of its financial reporting. These controls are the primary mechanisms for reducing fraud opportunity. They can be preventive, designed to stop fraud from happening in the first place, such as requiring dual signatures on checks. They can also be detective, designed to identify fraud after it has occurred, such as regular bank reconciliations. A well-designed system of internal controls is a fundamental component of any effective fraud prevention program and a key topic in the exam.

Fraud Risk Assessments

A fraud risk assessment is a systematic process that an organization undertakes to identify its specific vulnerabilities to fraud. It involves brainstorming potential fraud schemes that could affect the company, assessing the likelihood and potential impact of each scheme, and evaluating the effectiveness of existing controls designed to mitigate those risks.

The process often starts with interviews and workshops involving staff from different departments, since fraud risks can arise anywhere—from procurement and payroll to IT systems and vendor management. By including people from various levels of the organization, leaders gain a more comprehensive view of where risks may lie.

Once potential fraud schemes are identified, they are ranked by likelihood (how probable the scheme is) and impact (the financial or reputational damage it could cause). For example, payroll fraud in a large corporation may be more likely than collusion in vendor contracting, but vendor fraud may carry a much higher financial risk. Ranking these risks helps management allocate resources effectively.

The assessment also involves testing existing controls. This means examining whether policies, procedures, or internal checks are actually strong enough to prevent or detect fraud in practice. For instance, if two employees are supposed to approve a payment before it goes out, the fraud risk assessment would test whether this control is followed consistently or can be easily bypassed.

The results allow the organization to prioritize its anti-fraud efforts, closing the most significant control gaps first. This proactive and targeted approach is far more effective than a one-size-fits-all strategy. Fraud risk assessments are not a one-time exercise—they should be repeated regularly, especially after major organizational changes, mergers, or regulatory updates. For CFEs, the ability to design, lead, and interpret fraud risk assessments is a core skill that directly supports fraud prevention and organizational resilience.

The Path to CFE Exam Certification

Becoming a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) involves meeting a set of professional and academic requirements before taking the exam. Candidates typically need a bachelor's degree and at least two years of professional experience in a field related to fraud examination, such as accounting, auditing, law enforcement, investigation, or compliance.

The application process requires submitting proof of education and experience, along with professional recommendations. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), which administers the credential, reviews each application to ensure candidates meet the standards of integrity and professional readiness.

Once approved, candidates can schedule the CFE exam, which is a rigorous test of knowledge and skills across four key domains:

Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

Law

Investigation

Fraud Prevention and Deterrence

The exam is computer-based and can be taken online or at an approved testing center. It is designed to assess not only a candidate’s technical expertise but also their ability to apply concepts in practical, real-world scenarios. Passing the exam demonstrates mastery of fraud examination principles and qualifies professionals to carry the CFE designation.

The journey to becoming a CFE demands dedication, study, and often months of preparation. Many candidates use ACFE’s official prep course, while others supplement with practice questions, study groups, or professional workshops. However, the effort is well worth it: the CFE credential is recognized globally as the gold standard in fraud prevention and investigation. It opens doors to career advancement in auditing, compliance, government oversight, and corporate investigations.

Mastering Fraud Prevention and Deterrence for the CFE Exam

Fraud prevention and deterrence is one of the most forward-looking areas of the CFE exam. Unlike reactive investigations, this section emphasizes proactive strategies that organizations can use to reduce the risk of fraud occurring in the first place.

One critical approach is proactive fraud auditing. Traditional audits generally focus on past data and compliance with policies. In contrast, proactive fraud auditing looks for red flags and anomalies that may signal fraud is happening or about to happen. This often involves the use of data analytics, which allows examiners to sift through large volumes of financial and operational data. By using analytical techniques, auditors can spot unusual patterns—for instance, payments just below approval thresholds, duplicate expense claims, or payroll entries for “ghost employees.”

Another key tool in fraud prevention is the use of surprise audits and checks. When employees know that unannounced reviews of cash balances, inventories, or expense reports can occur at any time, the opportunity for fraud is significantly reduced. The unpredictability itself acts as a deterrent, discouraging potential fraudsters who might otherwise feel confident in avoiding detection.

Fraud prevention also extends into organizational culture. Companies that foster an ethical culture, emphasize integrity, and set a clear “tone at the top” from leadership tend to have lower instances of fraud. Codes of conduct, ethics training, and confidential reporting hotlines are examples of cultural tools that reinforce accountability. For the CFE exam, candidates should understand how these measures work together to form a comprehensive fraud prevention strategy.

In addition, fraud prevention relies on effective internal controls. Segregation of duties is one of the most powerful control measures, ensuring that no single employee has authority over all aspects of a financial transaction. For example, one employee may initiate a payment, another may approve it, and a third may record it. When duties are separated, opportunities for fraud shrink dramatically.

Technology also plays a growing role in deterrence. Automated monitoring systems, artificial intelligence, and continuous auditing software can now detect anomalies in real time. CFEs must understand not just the technical side of these tools but also how to implement them in a way that balances cost and effectiveness.

Finally, fraud prevention involves collaboration between departments. Human resources, IT, legal, compliance, and finance must work together to identify vulnerabilities and build a strong defense against fraud. Fraud is rarely confined to one area of a business, so exam candidates must think holistically when studying prevention strategies.

The COSO Framework and Internal Controls

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) Internal Control—Integrated Framework is a widely accepted model for designing, implementing, and evaluating internal controls. The framework is built on five interrelated components: the Control Environment, Risk Assessment, Control Activities, Information and Communication, and Monitoring Activities. For fraud prevention, the Control Environment, which refers to the "tone at the top" and ethical values, is the foundation. The other components build on this to create a comprehensive system that helps organizations manage their fraud risks effectively. Understanding this framework is essential for the CFE exam.

Segregation of Duties: A Cornerstone of Prevention

Segregation of Duties (SoD) is one of the most fundamental and effective internal control concepts. It is based on the principle that no single individual should have control over two or more phases of a transaction or operation. The goal is to prevent one person from being able to both perpetrate and conceal a fraudulent act in the normal course of their duties. For example, the person who authorizes a payment should not be the same person who signs the check, and neither should be the person who reconciles the bank account. This built-in checking mechanism significantly reduces the opportunity for fraud.

Physical and IT Security Controls

A comprehensive fraud prevention program must address both physical and digital assets. Physical security controls include measures like locks, security guards, and surveillance cameras to protect tangible assets such as cash and inventory from theft. In the modern era, information technology (IT) security controls are equally critical. These include firewalls to prevent unauthorized network access, encryption to protect sensitive data, and strict user access controls to ensure employees can only access the information necessary for their jobs. Both types of controls work together to create a secure environment that deters fraudulent activity.

Hiring and Employee Screening

An organization's fraud prevention efforts should begin before an employee is even hired. A thorough pre-employment screening process is a crucial step in identifying high-risk applicants. This process should include verifying educational and employment history, checking professional references, and conducting criminal background checks and credit checks where permissible by law. While not foolproof, these measures can help an organization avoid hiring individuals with a documented history of dishonesty or those who are under significant financial pressure, thereby reducing the risk of bringing a potential fraudster into the organization.

Developing a Code of Conduct and Ethics Training

A formal Code of Conduct is a document that sets out an organization's expectations for ethical behavior from all its employees, management, and directors. It should be written in clear, understandable language and provide guidance on handling ethical dilemmas, such as conflicts of interest or accepting gifts. However, simply having a code is not enough. It must be brought to life through regular and engaging ethics training. This training reinforces the organization's values, educates employees on specific fraud risks, and clarifies the procedures for reporting suspected misconduct, a key area for the exam.

Whistleblower Programs and Hotlines

According to ACFE research, tips are the most common way that occupational fraud is detected. Therefore, establishing a safe and accessible mechanism for employees and others to report suspected wrongdoing is one of the most effective anti-fraud controls. A successful whistleblower program includes a formal policy that protects reporters from any form of retaliation and provides multiple channels for reporting, such as a confidential, independently managed hotline. The presence of a well-publicized hotline acts as a strong deterrent, as potential fraudsters know that their colleagues have a safe way to report them.

Understanding Offender Psychology

To effectively prevent fraud, one must understand the mindset of the person who commits it. The Fraud Triangle provides the classic framework of pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. Fraud examiners must look for warning signs related to these elements. An employee living a lifestyle beyond their means may be under financial pressure. A domineering manager who overrides controls creates opportunities. An employee who feels underpaid or unappreciated may find it easier to rationalize theft. Recognizing these behavioral red flags can be just as important as identifying financial anomalies in preventing fraud.

The Role of Management in Fraud Prevention

The ultimate responsibility for fraud prevention rests with management and those charged with governance, such as the board of directors. Leaders must set an unequivocal ethical tone and foster a culture of integrity. They are responsible for overseeing the establishment and maintenance of an effective system of internal controls. Management must also ensure that fraud risk assessments are performed regularly and that the organization has a clear plan for responding to suspected fraud. A passive or disengaged management team creates a vacuum that can be easily exploited by fraudsters.

Preparing for the Fraud Prevention Exam Section

Success on the Fraud Prevention and Deterrence section of the CFE exam requires a thorough understanding of these proactive concepts. Candidates should focus on the principles of internal control, the elements of a comprehensive anti-fraud program, and the psychology behind why people commit fraud. The exam will test not just rote memorization but the ability to apply these concepts to practical scenarios. Using the ACFE's study materials, reviewing case studies, and taking practice exam questions are all effective strategies for mastering this critical domain of fraud examination.

Deconstructing Fraud Schemes for the CFE Exam

The ACFE's Fraud Tree is a foundational model used to classify the vast landscape of occupational fraud. It provides a clear and organized structure that is indispensable for any aspiring CFE. The tree is divided into three primary branches, each representing a major category of fraud: Asset Misappropriation, Corruption, and Financial Statement Fraud. Each of these main branches then splits into more specific sub-categories and schemes. Understanding this classification system is not just crucial for the CFE exam; it is essential for identifying and investigating fraud in the real world.

Asset Misappropriation: Cash Schemes

Asset misappropriation is by far the most common category of occupational fraud, and schemes involving cash are the most frequent within this category. These schemes are broadly divided into theft of cash on hand and fraudulent disbursements. A common example of theft of cash is skimming, which is the theft of cash before it is recorded in the accounting system. Fraudulent disbursements involve making payments for a fraudulent purpose. This includes billing schemes (creating a fake vendor), payroll schemes (creating a ghost employee), and expense reimbursement schemes (submitting falsified expenses).

Asset Misappropriation: Non-Cash Schemes

While cash is the most frequently targeted asset, non-cash assets are also vulnerable to theft and misuse. The most common non-cash misappropriation involves the theft of inventory. This can range from an employee stealing office supplies to a more sophisticated scheme involving falsifying shipping documents to divert goods to a personal location. Another form of non-cash fraud is the misuse of company assets, such as using a company vehicle for personal business. The theft of proprietary information, like trade secrets or customer lists, also falls into this category and can be incredibly damaging.

Corruption Schemes

Corruption schemes involve an employee using their influence in a business transaction in a way that violates their duty to the employer for the purpose of obtaining a direct or indirect benefit. This branch of the Fraud Tree includes several distinct types of schemes. Bribery involves offering or receiving something of value to influence an official act. Conflicts of interest occur when an employee has an undisclosed personal economic interest in a transaction. Other examples include illegal gratuities, which are rewards given for a business decision, and economic extortion, where an employee demands a payment to make a particular decision.

Financial Statement Fraud: The Least Common, Most Costly

While financial statement fraud is the least common of the three main categories, it is by far the most financially devastating on a per-case basis. These schemes involve the intentional misstatement or omission of material information in an organization's financial reports. The goal is typically to deceive investors, creditors, and other users of the financial statements. Common methods include recording fictitious revenues, concealing liabilities or expenses, improperly valuing assets, and failing to disclose significant information. These frauds are often perpetrated by senior management who have the authority to override controls.

Understanding the Red Flags of Fraud

For every type of fraud scheme, there are corresponding red flags that can signal its presence. These warning signs can be financial, behavioral, or systemic. For example, in a billing scheme, red flags might include invoices from a vendor with only a post office box for an address or payments to a vendor with a name very similar to an employee's name. A behavioral red flag for any type of fraud could be an employee who refuses to take vacations or who is unusually protective of their work area. A key skill for a CFE, and a major focus of the exam, is the ability to recognize these indicators.

Cyberfraud and Digital Schemes

In today's interconnected world, many traditional fraud schemes have been adapted for the digital environment, and new schemes have emerged. Business Email Compromise (BEC) is a prevalent scheme where a fraudster impersonates a senior executive or a vendor via email to trick an employee into making an unauthorized wire transfer. Phishing attacks attempt to steal sensitive information like login credentials or credit card numbers. Ransomware attacks encrypt an organization's data, holding it hostage until a payment is made. CFEs must be knowledgeable about these evolving digital threats.

Connecting Schemes to Prevention Controls

A critical aspect of fraud examination is understanding the relationship between specific schemes and the internal controls designed to prevent them. For instance, the risk of a ghost employee scheme can be mitigated by segregating the duties of human resources (who can add employees to the system) and payroll (who processes payments). The risk of inventory theft can be reduced through regular physical counts and reconciliations with inventory records. By understanding how a particular scheme works, a CFE can recommend and implement the most effective preventive and detective controls.

Exam Focus: Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

The Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes section of the CFE exam is one of the most content-heavy. It requires candidates to have a detailed knowledge of a wide variety of schemes, from simple expense fraud to complex financial statement manipulation. Preparation for this section should involve memorizing the definitions and mechanics of different schemes under the Fraud Tree. It is also important to be able to identify the red flags associated with each scheme and understand the accounting principles that are often manipulated to perpetrate them.

Case Studies in Fraud

Studying real-world fraud cases is one of the best ways to understand how these schemes are executed. Cases like Enron (financial statement fraud), WorldCom (capitalizing expenses), and the Wells Fargo account fraud scandal (unethical sales practices leading to falsified records) provide powerful lessons. Analyzing these cases helps to see how the elements of the Fraud Triangle came into play, which internal controls failed or were overridden, and what red flags were missed. These stories transform theoretical knowledge into tangible, memorable examples that are invaluable for exam preparation and professional practice.

The Art and Science of Fraud Investigation for the CFE Exam

A fraud investigation is a methodical process aimed at determining whether a fraud has occurred, who is responsible, and the extent of the financial loss. The process typically follows a structured lifecycle. It begins with receiving an initial allegation or identifying a red flag. This is followed by a preliminary assessment to determine if a full investigation is warranted. If so, the investigation moves into the planning phase, followed by evidence gathering, interviewing, and finally, reporting the findings to stakeholders. Each step requires a combination of technical skill, critical thinking, and professional judgment.

Sources of Allegations and Predication

Fraud investigations are initiated based on a variety of sources. As previously noted, tips from employees, vendors, or customers are the most common starting point. Other sources include findings from internal or external audits, management reviews of financial reports, or automated alerts from data analysis software. Regardless of the source, an investigator must establish "predication" before launching a full investigation. Predication is the totality of circumstances that would lead a reasonable, professionally trained, and prudent individual to believe that a fraud has occurred, is occurring, or will occur.

Planning the Investigation

Once predication is established, the investigation must be carefully planned. Rushing into evidence collection without a plan can compromise the investigation and even alert the fraudsters. The planning phase involves defining the objectives and scope of the investigation. What specific questions need to be answered? What time period will be covered? The plan should also identify potential suspects, outline the investigative steps to be taken, allocate resources, and establish a timeline. A well-developed investigation plan provides a roadmap that ensures the process is efficient, effective, and legally sound.

Gathering Evidence: Documents and Data

The core of any investigation is the collection and analysis of evidence. Documentary evidence is often paramount. This includes a wide range of materials such as invoices, purchase orders, bank statements, contracts, and electronic communications like emails and text messages. Investigators must know how to obtain these documents, both internally from the company and externally from third parties. Increasingly, evidence gathering involves data analytics, where investigators use specialized software to search for patterns, anomalies, and keywords in large volumes of electronic data, which is a key part of the CFE exam.

The Principles of Evidence Handling

Evidence in a fraud investigation must be handled with meticulous care to ensure it is admissible in any future legal proceedings. A crucial principle is maintaining the "chain of custody," which is a detailed log that documents who has handled the evidence, when, and for what purpose. This proves that the evidence has not been tampered with. Investigators must also ensure that evidence is properly marked, logged, and stored in a secure location. Understanding the difference between various types of evidence, such as direct versus circumstantial, is also fundamental knowledge for a fraud examiner.

Interviewing Witnesses and Subjects

Interviewing is a critical skill for every fraud examiner. The ability to obtain information from people is often what makes or breaks an investigation. There are different types of interviews. Informational interviews are conducted with neutral third-party witnesses to gather background information. Admission-seeking interviews are conducted with the primary suspect with the goal of obtaining a confession. Effective interviewing involves careful planning, building rapport, using strategic question types (open-ended, closed-ended), and observing the interviewee's verbal and non-verbal reactions. The exam heavily tests these concepts.

Covert Investigations and Surveillance

In some cases, investigators may need to employ covert methods to gather evidence. This might include conducting surveillance to observe a suspect's activities or, in rare cases, using an undercover operative to gather information from within a group. These techniques are high-risk and must be conducted with extreme caution and in strict compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. They are generally used only when there is strong predication and when other, less intrusive methods are not feasible. The ethical and legal implications of such actions are significant.

Tracing Illicit Transactions

A central part of many fraud investigations is "following the money" to determine where stolen funds have gone. This requires a specialized set of financial investigation skills. Examiners analyze bank statements, credit card records, and other financial documents to trace the flow of funds from the victim to the perpetrator. They may use techniques like the net worth method, where a suspect's assets and liabilities are analyzed to identify unexplained increases in wealth. This process can be complex, especially when fraudsters use shell corporations, offshore accounts, or digital currencies to launder their illicit gains.

Reporting the Findings

The final stage of the investigation is to communicate the findings in a formal written report. The investigation report should be clear, concise, objective, and based solely on the evidence gathered. It should detail the predication for the investigation, the steps taken, the evidence collected, and the ultimate conclusions. The report should present the facts without expressing opinions on the guilt or innocence of any individual. This document becomes the official record of the investigation and may be used in legal proceedings, so it must be accurate and professionally written.

Preparing for the Investigation Exam Section

The Investigation section of the CFE exam tests the candidate's understanding of the entire investigative process, from planning to reporting. Success requires knowledge of evidence handling rules, interview techniques, and various methods for gathering and analyzing information. Candidates should focus on the systematic approach to investigation. Studying the ACFE's official materials, which provide detailed guidance on these topics, and practicing with scenario-based questions will help build the confidence and knowledge needed to excel in this part of the exam and in the field.

Navigating the Legal Landscape of Fraud for the CFE Exam

A Certified Fraud Examiner operates at the intersection of accounting and law. Therefore, a solid understanding of the legal framework is essential. Fraud cases can be pursued in two primary legal arenas: the criminal justice system and the civil justice system. Criminal cases are brought by the government to punish wrongdoing, with a high burden of proof ("beyond a reasonable doubt"). Civil cases are brought by victims to recover their losses, with a lower burden of proof ("preponderance of the evidence"). A CFE must understand the procedures, rules, and potential outcomes in both systems.

Key Legal Elements of Fraud

For an act to be legally considered fraud, a specific set of elements must typically be proven in court. While the exact definition can vary by jurisdiction, it generally involves a material false statement made with knowledge of its falsity (scienter). There must also be an intent to induce the victim to act, the victim's justifiable reliance on the false statement, and resulting financial damages. A fraud examiner's investigation is often focused on gathering evidence to support each of these legal elements, providing the foundation for a successful legal action.

Criminal Law and Fraud Statutes

Many specific laws make fraudulent activities a crime. In the United States, for example, federal statutes cover a wide range of offenses, including mail fraud (using the postal service to commit fraud), wire fraud (using electronic communications), and bank fraud. There are also laws specifically targeting money laundering, which is the process of concealing the origins of illegally obtained money. Fraud examiners often work closely with law enforcement and prosecutors to build cases based on these statutes, and knowledge of them is critical for the exam.

Civil Law and Torts

In addition to criminal charges, individuals and organizations that commit fraud can be sued in civil court. These lawsuits are typically based on legal concepts known as torts, which are civil wrongs that cause someone else to suffer loss or harm. Torts relevant to fraud cases include fraudulent misrepresentation, concealment, and breach of fiduciary duty. A successful civil lawsuit can result in a court ordering the defendant to pay compensatory damages to make the victim whole, and in some cases, punitive damages to punish the wrongdoer.

Rights of Individuals in an Investigation

During an investigation, it is imperative that a CFE respects the legal rights of everyone involved, including witnesses and the accused. In a corporate setting, employees may have certain rights regarding privacy in their workspace and communications. If the investigation becomes a criminal matter, constitutional protections, such as the right to counsel and the privilege against self-incrimination, come into play. A fraud examiner must be careful not to violate these rights, as doing so could jeopardize the investigation and expose the examiner and their employer to legal liability.

Testifying as a Witness

A fraud examiner's work often culminates in them testifying in a legal proceeding, such as a deposition, a hearing, or a trial. They may testify as a fact witness, describing the steps of their investigation and the evidence they found. Alternatively, they may be qualified as an expert witness to offer their professional opinion on matters such as the adequacy of internal controls or whether certain transactions appear fraudulent. Effective testimony requires thorough preparation, clear communication, and the ability to remain composed and objective under cross-examination.

Bankruptcy (Insolvency) Fraud

Bankruptcy proceedings are a specialized area where fraud can be particularly prevalent. These frauds occur when a debtor conceals assets to prevent them from being distributed to creditors, or when false information is submitted in bankruptcy filings. Examples include knowingly making a false oath, concealing property, or making a false claim. CFEs are often engaged to investigate potential bankruptcy fraud, helping trustees and creditors identify and recover hidden assets for the benefit of the bankruptcy estate. The CFE exam requires a foundational understanding of these specific schemes.

Securities Fraud

Securities fraud encompasses a broad range of deceptive practices related to the stock and commodities markets. This can include insider trading, where an individual trades stock based on confidential information not available to the public. It also includes market manipulation schemes designed to artificially inflate or deflate a stock's price. Another major area is the dissemination of false information in documents filed with regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). These are complex financial crimes that often result in significant investor losses.

Ethical Obligations for CFEs

The credibility of a Certified Fraud Examiner hinges on their commitment to the highest ethical standards. The ACFE Code of Professional Ethics provides the guiding principles for the profession. It requires CFEs to demonstrate a commitment to professionalism, to avoid conflicts of interest, and to not engage in any illegal or unethical conduct. It also mandates that they maintain strict confidentiality, exhibit objectivity in their work, and continuously strive to increase their professional competence and effectiveness. Adherence to this code is not optional; it is a core requirement for maintaining the CFE certification.

Preparing for the Law Exam Section

The Law section of the CFE exam can be one of the most challenging for candidates without a legal background. Preparation should focus on understanding the fundamental legal principles that underpin fraud cases rather than trying to memorize every specific law. Key areas of focus should include the elements of fraud, the differences between the civil and criminal justice systems, the rules of evidence, the rights of individuals, and the ethical responsibilities of a CFE. Using flashcards for legal terms and working through practice questions related to legal scenarios can be particularly helpful.

Conclusion

The journey to earning the Certified Fraud Examiner credential, culminating in the rigorous CFE exam, is a transformative process that extends far beyond academic achievement. It represents a deep commitment to upholding integrity and combating financial crime in an increasingly complex global economy. This five-part series has navigated the core domains of this profession, providing a roadmap through the vast body of knowledge required to become a CFE. We began by establishing the foundation, understanding the prestigious role of a CFE, and delving into the psychology of fraudsters through the lens of the Fraud Triangle. The first pillar, Fraud Prevention and Deterrence, emphasized the paramount importance of proactive measures—building an ethical culture, designing robust internal controls, and conducting thorough risk assessments to lock the door on fraud before it can even enter.

From there, we journeyed into the intricate world of criminal ingenuity by deconstructing the ACFE's Fraud Tree. We explored the myriad ways employees can exploit their positions, from common asset misappropriation schemes involving cash and inventory to complex corruption and the devastating impact of financial statement fraud. Recognizing the red flags and understanding the mechanics of these schemes are the diagnostic skills that allow a CFE to identify illness within an organization's financial health. This knowledge forms the bedrock upon which all subsequent investigative and legal actions are built, ensuring that examiners know precisely what they are looking for amidst a sea of transactions.

The series then transitioned from theory to practice, detailing the art and science of fraud investigation. We outlined the methodical process that defines a professional inquiry, from establishing predication and meticulous planning to the careful gathering of evidence and the delicate skill of interviewing. This section highlighted that a successful investigator is part scientist, applying analytical rigor to data and documents, and part artist, using intuition and interpersonal skills to uncover the truth. The ability to follow the money, handle evidence impeccably, and report findings with absolute objectivity is what distinguishes a CFE and ensures their work can withstand the intense scrutiny of legal proceedings.

Finally, we navigated the complex legal landscape that governs the entire profession. Understanding the fundamental differences between criminal and civil law, the specific legal elements required to prove fraud, and the rights of every individual involved is non-negotiable. A CFE must be as comfortable discussing the rules of evidence as they are discussing accounting principles. This legal acumen, combined with a steadfast commitment to the ACFE Code of Professional Ethics, ensures that a fraud examiner acts not only effectively but also righteously, protecting the integrity of the investigation and the profession as a whole.

the path to passing the CFE exam and becoming a Certified Fraud Examiner is a challenging but profoundly rewarding endeavor. It equips professionals with a unique and powerful skill set that is in constant demand across every industry. CFEs are the guardians of financial integrity, the detectives of the corporate world, and the champions of ethical business practices. The knowledge gained through preparing for the CFE exam empowers individuals to protect assets, preserve reputations, and promote justice. For those who embark on this journey, it is more than just a certification; it is an entry into a global community of experts dedicated to fighting fraud and making the business world a more honest and transparent place. The CFE credential is a testament to expertise, a commitment to ethics, and a key to a career filled with purpose and impact

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I download my products after I have completed the purchase?

Your products are available immediately after you have made the payment. You can download them from your Member's Area. Right after your purchase has been confirmed, the website will transfer you to Member's Area. All you will have to do is login and download the products you have purchased to your computer.

How long will my product be valid?

All Testking products are valid for 90 days from the date of purchase. These 90 days also cover updates that may come in during this time. This includes new questions, updates and changes by our editing team and more. These updates will be automatically downloaded to computer to make sure that you get the most updated version of your exam preparation materials.

How can I renew my products after the expiry date? Or do I need to purchase it again?

When your product expires after the 90 days, you don't need to purchase it again. Instead, you should head to your Member's Area, where there is an option of renewing your products with a 30% discount.

Please keep in mind that you need to renew your product to continue using it after the expiry date.

How often do you update the questions?

Testking strives to provide you with the latest questions in every exam pool. Therefore, updates in our exams/questions will depend on the changes provided by original vendors. We update our products as soon as we know of the change introduced, and have it confirmed by our team of experts.

How many computers I can download Testking software on?

You can download your Testking products on the maximum number of 2 (two) computers/devices. To use the software on more than 2 machines, you need to purchase an additional subscription which can be easily done on the website. Please email support@testking.com if you need to use more than 5 (five) computers.

What operating systems are supported by your Testing Engine software?

Our testing engine is supported by all modern Windows editions, Android and iPhone/iPad versions. Mac and IOS versions of the software are now being developed. Please stay tuned for updates if you're interested in Mac and IOS versions of Testking software.